![]() Growing up, I was mildly obsessed with Mount Everest. Even now I marvel at its wonderful geology.

Growing up, I was mildly obsessed with Mount Everest. Even now I marvel at its wonderful geology.

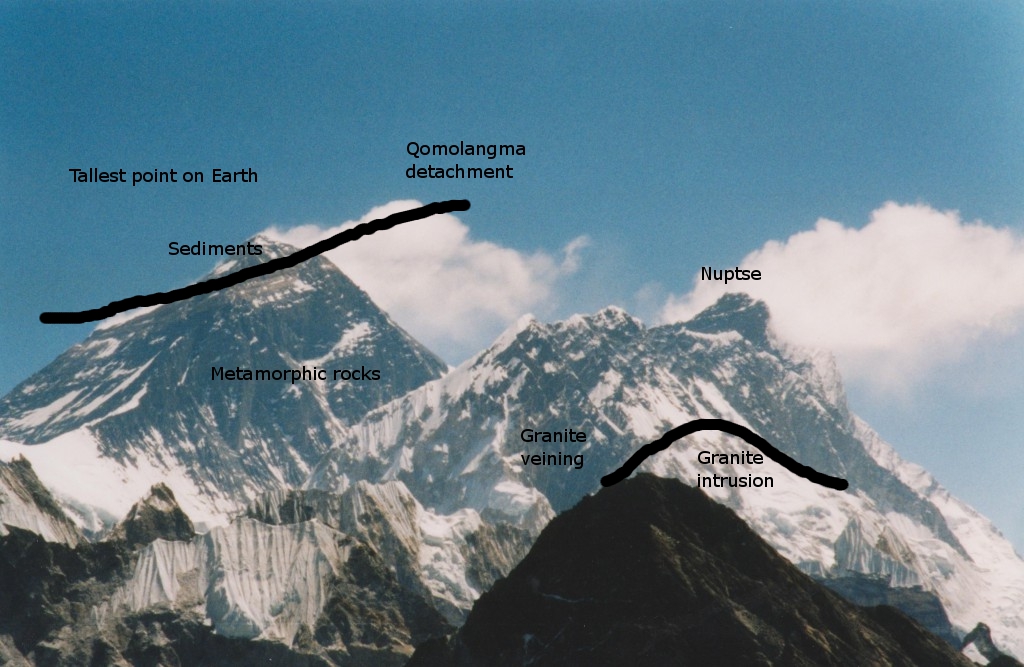

Looking at that, who can blame me?

My youthful obsession was fuelled by books of British expeditions in the 1970s climbing it by various routes with varying levels of success. The photos were the best; an image by Doug Scott showing Everest, Lhotse and Makalu, taken by from Kangchenjunga was particularly mesmerising. <aside> Makalu (left-hand of 3 tall peaks) in particular is intriguing as it looks like it had a glacial ‘U-shaped’ valley that has now mostly fallen away in landslides. If you know more, please tell me! </aside>. I started my teenage years wanting to climb mountains like this, but by the end of my teens this had waned. It was too apparent that many people in the early books had been killed on the mountains. Now that Everest seems full to the seams with the rich and the foolish – littered with their corpses – the glamour has worn off somewhat.

It was still a great thrill to go on a walking holiday to the Everest region, particularly as by then the geology of the area was properly understood. I shall use my pictures to illustrate the geology, as described in a 2003 paper by Mike Searle and colleagues, available on line via his Everest map website.

Let’s revisit that first picture.

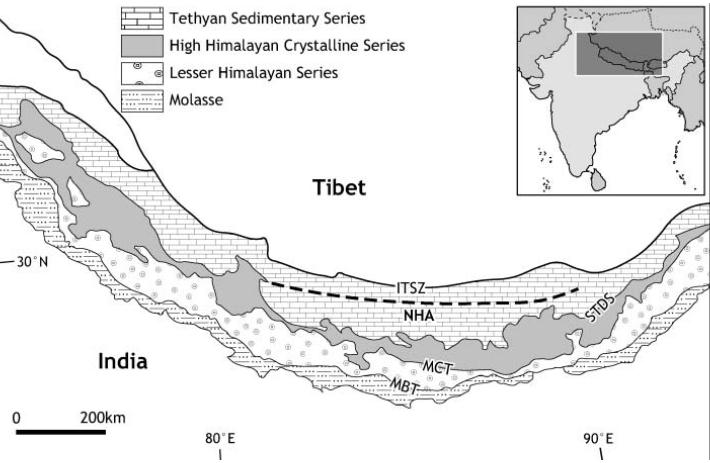

This shows the main features, north is to the left. The summit area is made of sedimentary rocks, now far from the sea. The contact with the metamorphic rocks is not an unconformity, but an extensional detachment: a structure – here brittle fault, there shear zone- that is usually associated with thinning of the crust. The Qomolongma detachment, together with the Lhotse detachment (in my picture, hidden in the Western Cwm, the valley between Everest and Nuptse) together are part of the South Tibetan Detachment System (STDS) which can be traced along the entire Himalayan chain

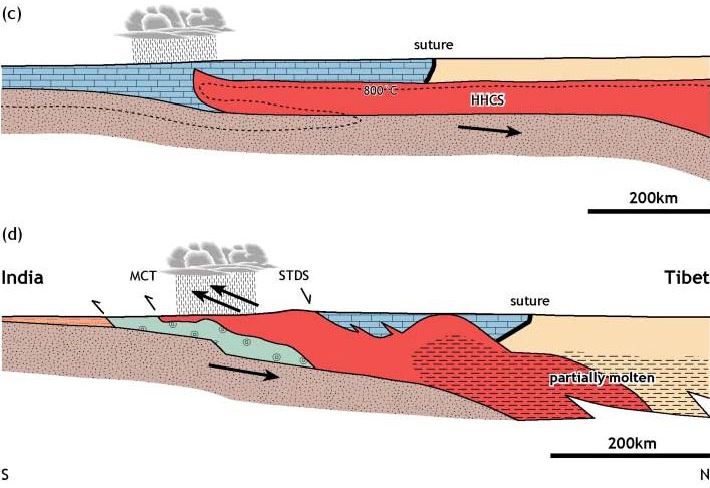

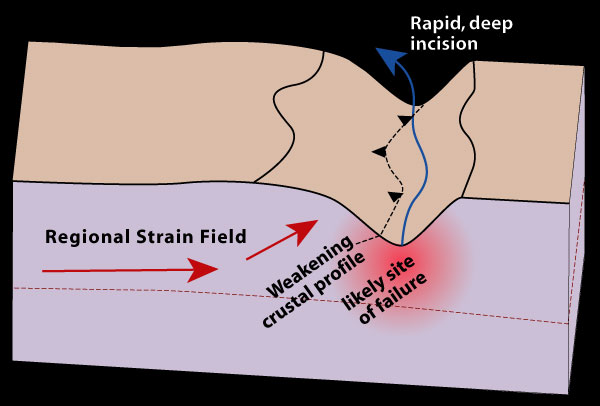

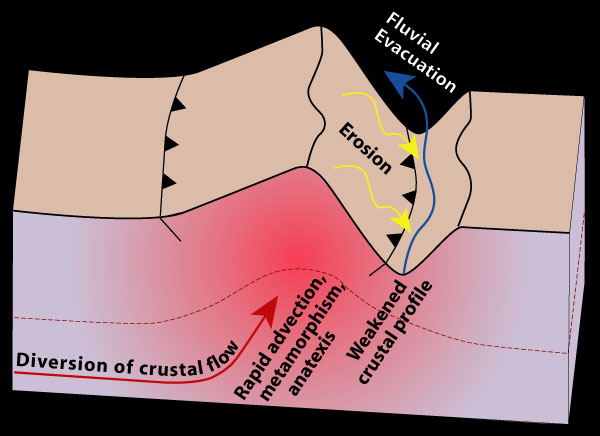

The rocks labelled as metamorphic rocks are greenschist facies, but the Nuptse ridge (right hand side of picture) contains high-grade sillimanite gneisses and many granite intrusions. These are part of a package of high-grade metamorphic rocks, the High Himalaya Crystalline series that are everywhere found below the STDS. Searle and colleagues explain these rocks in terms of channel flow. This amazing theory says that between 21 and 16 million years ago, a thick channel of soft hot rocks flowed out from under the Tibetan Plateau towards the Himalayas.

The Qomolangma detachment is part of the top of this channel. The high-grade rocks below flowed 200km south into their current position, moving at a shallow angle parallel to the top of the channel. The driving force for all of this? The snow and rain falling on the mountains and eroding the surface.

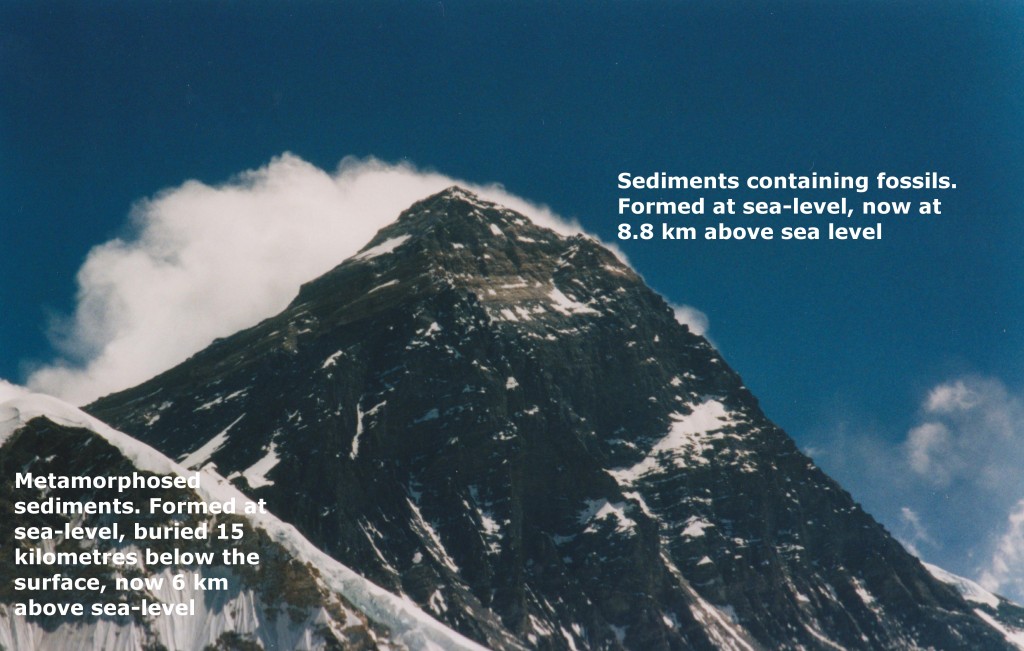

Let’s look at the rocks in more detail. Above is a picture of Changtse in Tibet, taken from near the head of the Khumbu valley in Nepal. It is looking up and north at the Qomolangma detachment. The prominent yellow band, often mentioned by mountaineers, is marble and lies just below the detachment. Above are unmetamorphosed sediments. Left in the foreground is mostly granite.

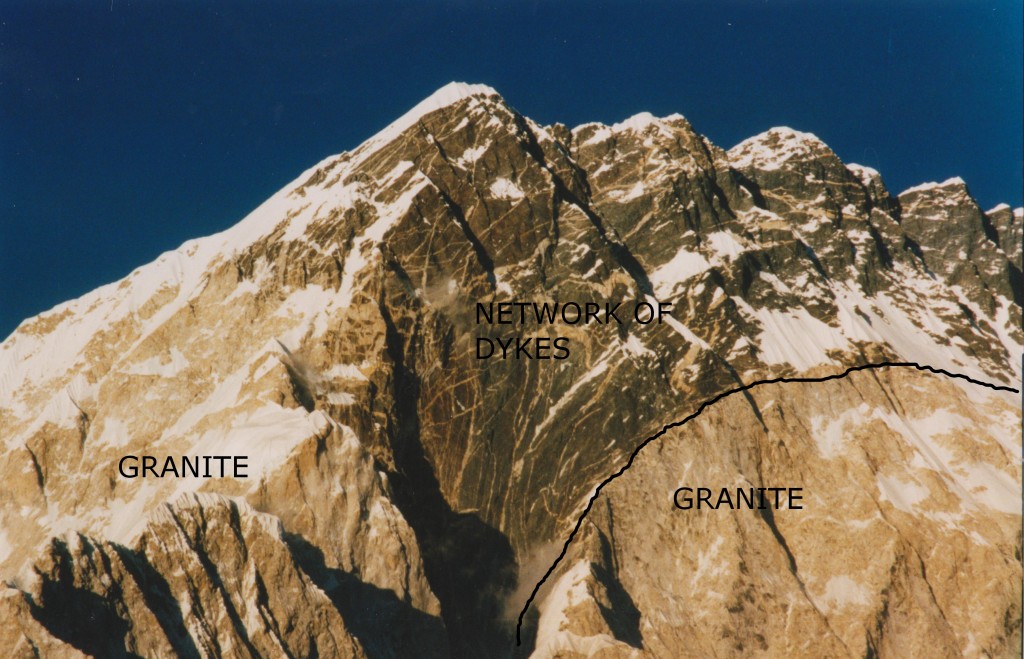

Turning to the metamorphic ‘channel’ rocks lets look at the South face of Nuptse, from a more direct angle.

The picture is around 3 kilometres from top to bottom. The dark rocks are high-grade gneisses, that flowed 200km towards the camera. A clue as to how they did that is found in the pale areas – granite. Rocks containing melt have a much lower viscosity. The many dykes/veins in above the granite are, according to Searle, an “explosive network of dykes emanating out of the top of the Nuptse–Everest leucogranite” caused by late-stage volatile rich magma. In other words, the fluid left behind as the main intrusion cooled and solidified.

Searle interpret the right-hand granite body as a sill that ballooned into a much thicker body. It passes under the summit of Everest and an equivalent body is found in the east Kangshung face of Everest. They speculate that the presence of this 3km thick granite body might explain the particularly high mountains.

Another view there, in different light with some moody clouds.

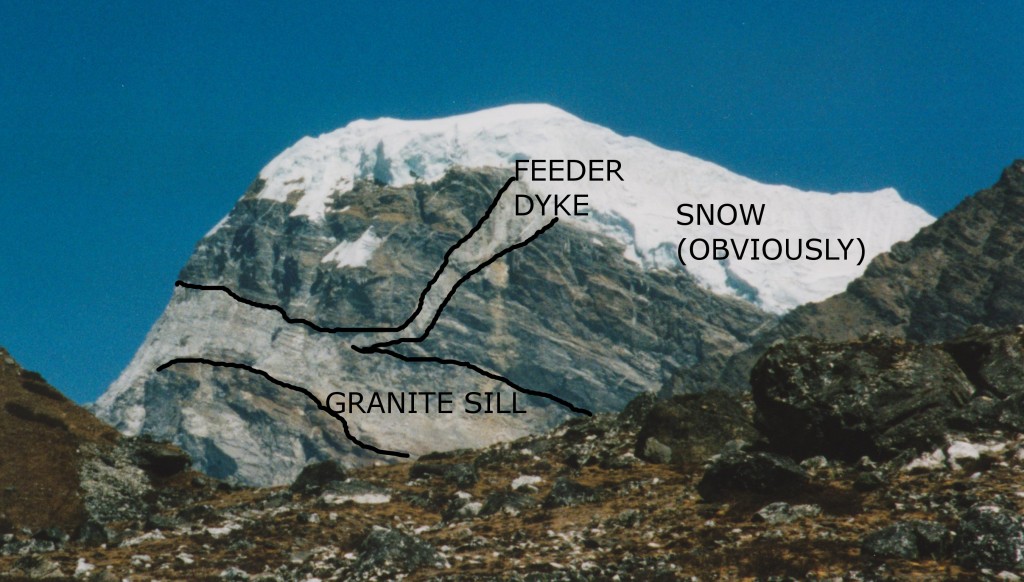

This is a view of an unnamed mountain on the side of the Khumbu valley. It shows a more typical view of the granite intrusions in the area, plus a glimpse of how it was intruded.

Granite sills are typical of the area, but the dyke was the only one I saw. The intrusion process was of sills making space via hydraulic fracturing along bedding/foliation planes in the dark metamorphic rock. Dykes allow flow between sills.

In the 30’s and 50’s mountaineers on Everest were also explorers and they collected samples One geologist, Lawrence Wager, got to with 300m of the summit in 1933 and later became Professor of Geology at Oxford (my alma mater) . One paper on Everest geology (Jessup et al 2006) is a detailed study of microstructures. It involved studying Wager’s samples, plus others collected on the 1953 expedition. One was collected by Edmund Hilary only 12 metres below the (snow-covered) summit. Either just before or just after he became the first man on the Earth’s highest point, he took the time to collect a rock sample. Mount Everest and geology are closely intertwined.

References and further reading

![]()

SEARLE, M., SIMPSON, R., LAW, R., PARRISH, R., & WATERS, D. (2003). The structural geometry, metamorphic and magmatic evolution of the Everest massif, High Himalaya of Nepal-South Tibet Journal of the Geological Society, 160 (3), 345-366 DOI: 10.1144/0016-764902-126

The Searle paper came out of joint research between Oxford and Virginia Tech universities. Both have websites with more gorgeous pictures. The Oxford one has a low-res version of a map made of the area and includes a copy of the Searle paper. The Virginia Tech one has pictures linked to a map.

Ron Schott has compiled a list of Gigapans from the Himalayas, including a few from the Everest region.

You can find more on the Wager / Everest connection online. If you want to see a photomicrograph of the highest rock sample ever collected, figure 6 of the Jessup et al paper is the place to go.

This post is the summit of my journey into the Geology of mountains. If you want more detail on channel flow and associated concepts, that’s the place to go.