This is the third part of a set of posts describing a walk I took across Cheshire. My goal was to find out everything that was interesting about the places I visited. Previously I’ve seen traces of apocalypse and traced the layers of the landscape.

Dropping off the ridge, the wind suddenly stops and everything feels very different. I’m walking down towards a deep river valley, quite unlike the surrounding area. Rivers hereabouts tend to feel rather incidental, hemmed in by ridges of sandstone, man-made dams, or simply too small to matter. Shell Brook is an exception (brook is one of the many English words for stream). Sitting on an unusually large expanse of soft shale, overlaid by softer glacial boulder clay it is a proper dendritic stream that has made a big hole in the ground.

View of the top of Shell Brook. The peak is Shutlingsloe and the clump of trees contains Cleulow Cross, site of an ancient barrow. Note that the sheep are staring at me.

Shell Brook is also unusual for being so full of trees. Apart from the horrid industrial evergreens of Macclesfield Forest – planted to make pit-props in coal mines that have since been shut – woodland is rare in these parts.

If you look at a geological map of the area and toggle the geological overlay, there is a clear pattern. The gentle upper slopes of the valley, covered in glacial sediment and free of trees. Closer to the river it has cut down to the shale beneath and this area is mostly wooded.

On the way down into the valley, there is a ruined farmhouse, Mareknowles.  It’s an old building, started in local sandstone and extended in rough bricks. The roof tiles are local flag stones. If the house had been built in the 20th or even late 19th century it would almost certainly have been built with thinner lighter slates from North Wales.

It’s an old building, started in local sandstone and extended in rough bricks. The roof tiles are local flag stones. If the house had been built in the 20th or even late 19th century it would almost certainly have been built with thinner lighter slates from North Wales.

You can trace the change in use. Windows lose glass and are bricked up. A layer of ancient dung indicates it was used to house livestock. Vivid white streaks down the inner wall suggest local buzzards live here now.

It is genuinely surprising to see a wrecked house here. High demand for housing combined with planning restrictions on rural areas mean that old buildings in nice bits of England are usually converted into expensive dwellings. I would be very happy to live with a view like this.

After a steep descent, my first glimpse of the river is a little surprising. Did such a small thing make such a big hole? It seems it did.

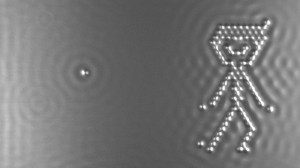

Once I reached the stony stream bed I look for fossils (of course). The second piece I pick up has this beauty on it: a ridged bivalve, a fossil shell – what else would you expect from Shell Brook?

I cheated a little, making sure I met the stream where the geological map marks a ‘marine band’. These rocks were deposited during times (like today) when distant Ice Caps caused periodic fluctuations in sea level (more here). Times of high sea level brought sea water into this area, leaving muds rich in fossils.

This is a quiet spot. Nearly 200 years ago, it was affected by the world’s first phase of industrialisation and the introduction of an important transportation technology: canals.

Macclesfield Canal was brought in to link the industrial towns of Macclesfield and Congleton to the wider world. Road transport was inefficient; although Macclesfield was linked to the turnpike system, there were cheaper ways of shifting goods than a horse and cart. Places with navigable rivers were more fortunate – a boat can carry a big load. So in 1826 they started to build a man-made river, a canal.

Britain’s canals are waterways that join up the country. They are narrow shallow waterways with long flat sections and little flow of water. Long thin shallow boats can be heavily laden and yet pulled by horses that walk along the tow-path. Some are triumphs of engineering. Keeping canals flat, yet tracing them across a bumpy landscape may require tunnels (no horses here, men would lie on the roof of the boat and push against the tunnel roof to move), aqueducts or locks (to link two sections of canal at different heights).

Locks lift boats up by flowing water down. All of this water must be managed somehow and this is where Shell Brook comes in. When the canal was built in To feed the canal, a new reservoir was built near Bosley. To feed the reservoir, they weren’t allowed to use the main river in the area, the Dane so they turned to its tributaries. They built a small channel from Shell Brook, that travels 5km to Bosley Reservoir. It is fairly flat, so it follows the contours right round to the other side of Wincle Minn ridge where it joins a network of channels (marked as ‘conduit’ on Ordnance Survey maps). Neatly, one of these conduits follows the trace of a glacial meltwater channel – a line scooped out of the hillside by water flowing underneath or alongside the major Ice Sheet that covered this land around 10,000 years ago.

Engineers built things to last then, lots of traces remain.

Where the conduit meets the stream

No doubt water in the canal is managed by pumps these days – the channel is somewhat neglected. But I disturbed a heron while walking along here, so someone likes it.

This is barely a path, mostly used by sheep, but it still deserved a little bridge over the conduit.

This tracery of industry, wriggling up from the plain into the edge of Cheshire is rather neglected now. I kept seeing traces of neglect.

The lower horizontal branches of this straggly bush show that it was once part of a managed hedge. The technique of hedge-laying, part cutting of branches and laying them flat to get a thick barrier to livestock, is little practised these days.

After a pleasant walk along the Dane Valley I arrived in Wincle, passing the place where last night’s pint came from.

Note the colour of the stone. In Britain this red-pinkness is associated with the desert sandstones of the New Red Sandstone. Yet these rocks are the older Carboniferous ones. New Red Sandstone is found nearby sitting on top, the old desert surface was not far above us. These 300 million year old sandstone were nearly exposed 250 million years ago and stained by the desert conditions.

Beyond Wincle we move into Gawain and Green Knight territory. A classic of english Medieval literature, it is written in a dialect from this area. The climactic scene takes place in an eerie Green Chapel. Many believe it is based on a real place – a nearby chasm formed by landslip, Ludchurch. Reading it makes you see the place with new eyes. The depictions of hunting are a reminder of why nearby “Wildbercluff” is written Wildboarclough. Viewing the crags from the route Gawain would have taken to the Green Chapel, its tempting to see them as the “ru3e knokled knarrez with knorned stonez” (rough, rugged rocks) of the poem.

ru3e knokled knarrez with knorned stonez

One of the mysteries of the poem is the meaning of the word “wodwo”. From the context it is some type of wild thing. Crossing this stile there is a funny wooden post that can be lifted up to let your small dog (or your wodwo) through.

The Roaches are part of the High Peak, a browner more desolate landscape. I’ve crossed the edge of Cheshire now and reached wilder lands (Derbyshire!). My journey is over.