Using many different techniques, dozens of scientists are studying the death of an ice sheet that once covered Britain and Ireland. They want to understand the future fate of modern-day ice.

The phrase “ice sheet” doesn’t do justice to our subject: this is not something you shatter when stepping on a frozen puddle. Covering over a million square kilometres, this sheet is also kilometres thick. As it grew it pulled enough water out of the world’s oceans to lower them by metres, affecting tropical coastlines as well as the land entombed beneath the ice. The vast bulk even pushed down the crust beneath, slowly moving the underlying mantle aside.

Melt pond on ice sheet. Photo by Leif Taurer used under Creative Commons.

The ice is constantly in motion. Snow falling on the ice sheet will eventually make its way to the sea, slowly flowing down and along. Most is channelled into fast moving ice-streams. This ice sheet is ‘marine-influenced‘, it sits partly on land, partly on the sea – most of its ice will end its days as an iceberg. The edges of the sheet can become undercut by the oceans, turning the edge into delicate ice shelves.

In the way it grows and flows, this ice sheet can seem almost alive. It will surely die, one day. Changing climate tips the balance between snow build-up and melting, the unstable ice shelves collapse and the ice-streams send ice to melt in the sea. In time the sheet thins to nothing and the world is transformed again.

BRITICE-CHRONO

My description of an ice sheet applies to the modern West Antarctic sheet. Scientists who study it worry about how, in the face of a rapidly changing climate, it might collapse, flooding cities across the globe. The IPCC identified this risk and highlighted how little we know about it.

My description also applies to the ice sheet that sat over Britain & Ireland 25,000 years ago.. A multi-disciplinary consortium, called BRITICE-CHRONO will greatly improve our understanding of the death of this ice sheet. This will be of great local interest, but will also help us predict the potentially troubled and troubling future of both the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. The ancient climate change that killed the ice sheet was natural, but modern human-made warming melts ice just the same.

BRITICE

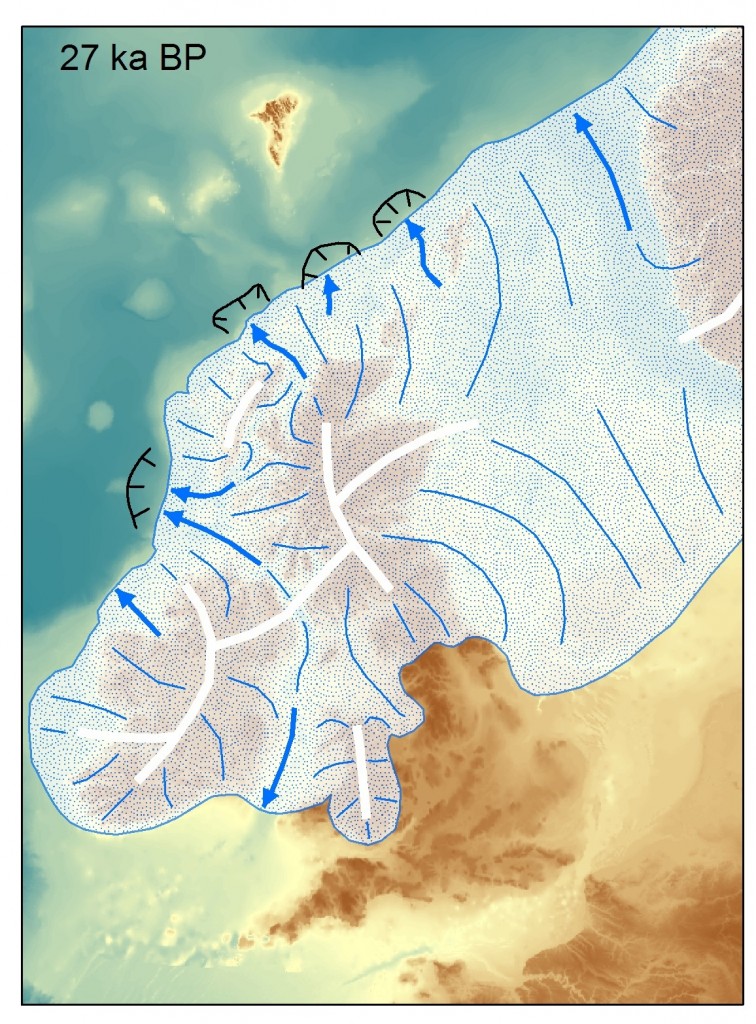

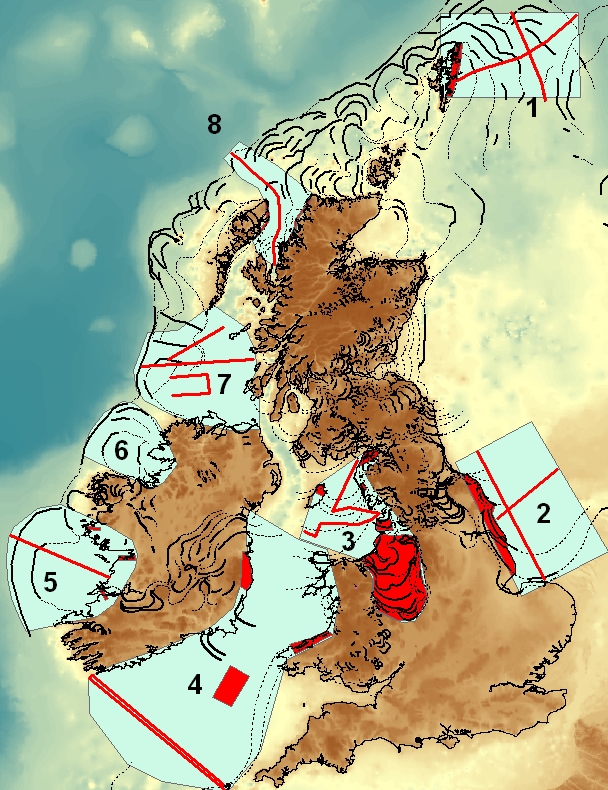

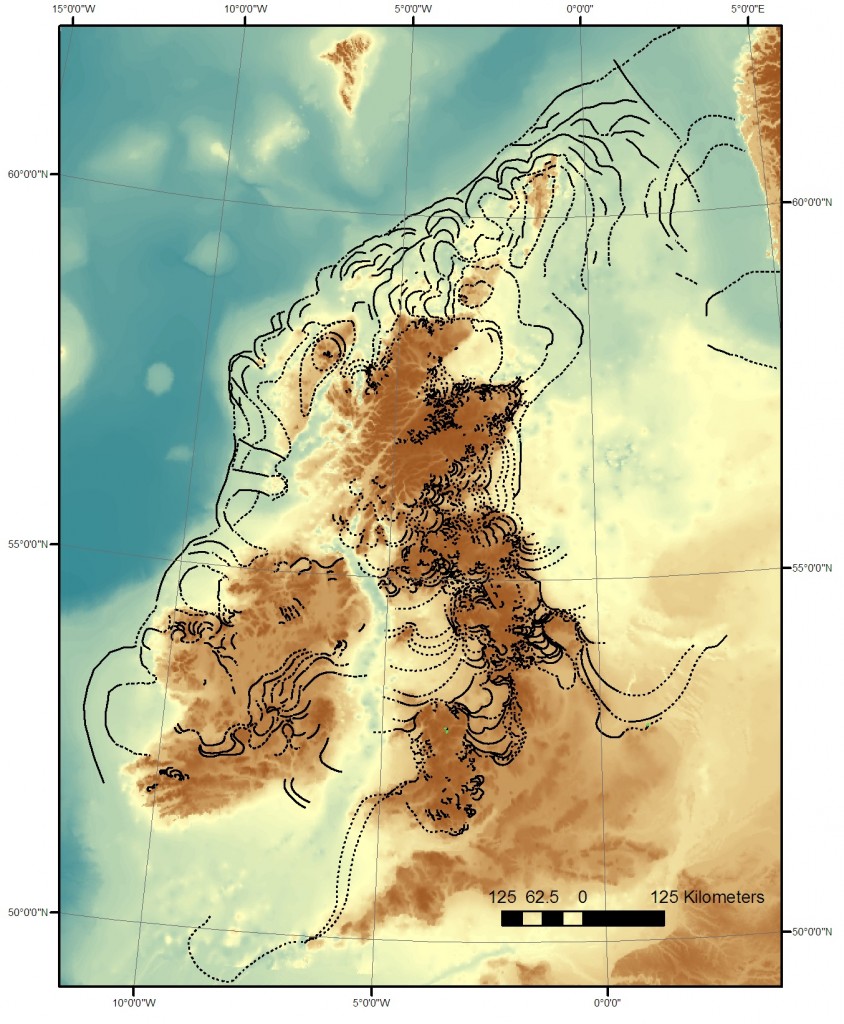

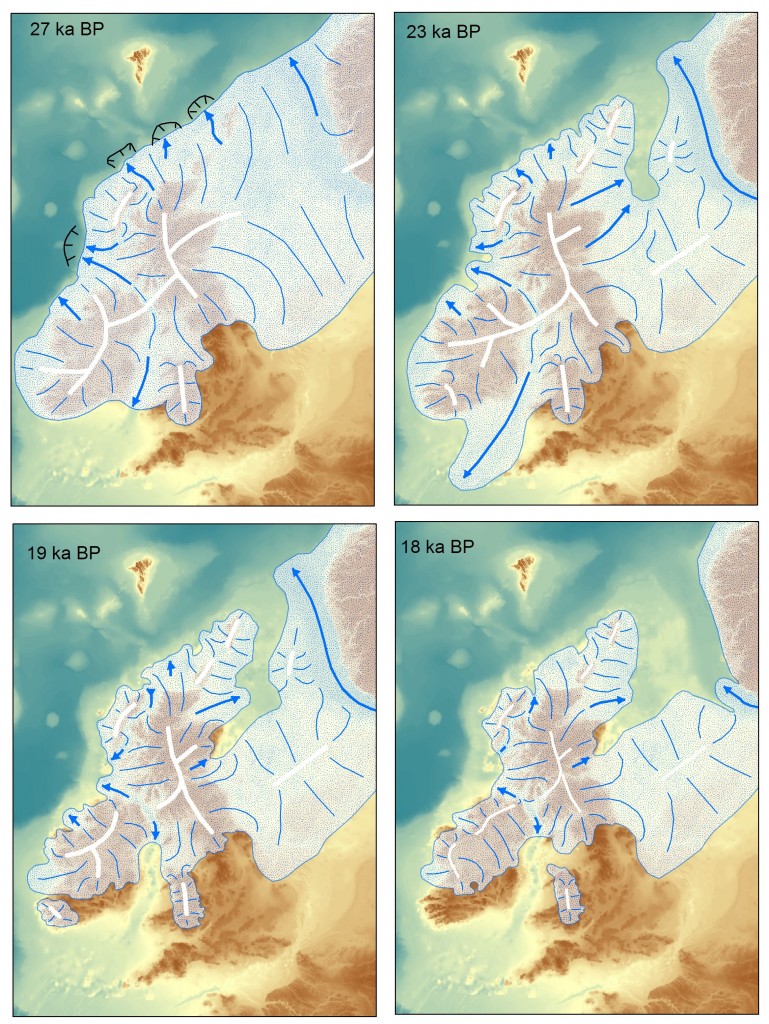

The physical traces of the death of the British ice sheet are easy to find: erratics, moraines and glacial lake deposits are just a few of the subtle but distinctive features to found over much of Britain. A now complete project called BRITICE, led by Professor Chris Clark of Sheffield University, mapped them all, focussing on traces of the final retreat of the ice sheet. Similar work in Ireland allows the pattern of retreat for the entire ice sheet to be inferred.

Maps showing the evolution of the British & Irish ice sheet over time. “19 ka BP” means 19,000 years before present. Image from Chris Clark.

CHRONO

BRITICE-CHRONO involves nearly 50 researchers from 8 universities plus the British Antarctic and Geological Surveys. A big part of the work of BRITICE-CHRONO is working out the age of various features. Familiar techniques such as radiocarbon dating are useful, but a new generation of dating techniques can do things that seem almost magical.

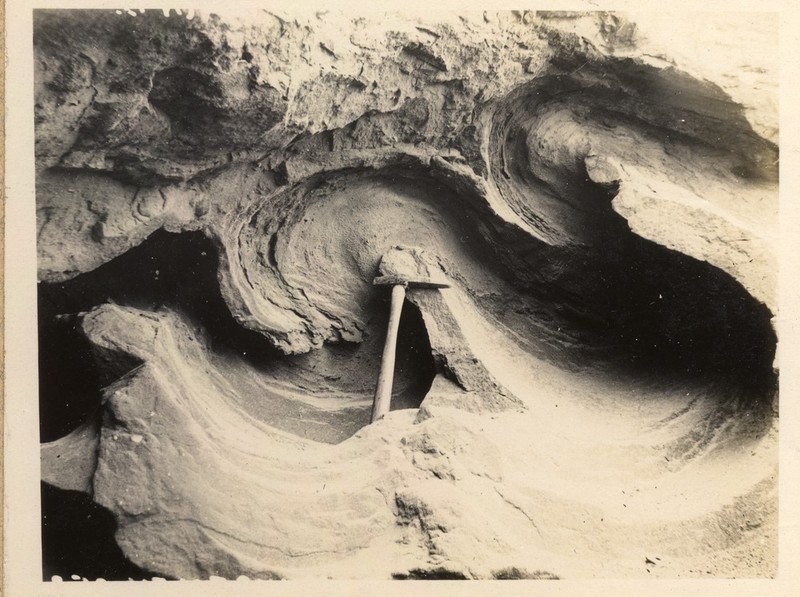

Optical stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates the last exposure of sunlight for individual quartz grains. Natural radioactivity traps electrons within defects in the crystal lattice of the quartz grains. If light comes through it frees them again and produces more light (the luminescence). Quartz exposed to sunlight at the surface does not show luminescence, but grains that have been buried in a sand bank for thousands of years do. Measuring luminescence in the lab allows an estimate how long they have been buried for and therefore when the sand was deposited.

Conversely, TCN (terrestrial cosmogenic nucleides) is a technique used for dating how long a surface has been exposed. Cosmic radiation is constantly streaming down on us and within minerals at the Earth’s surface it produces radioactive elements such as 10Be and 36Cl. The more of these we find, the longer the surface has been exposed to space. Apply this technique to a boulder dropped by a glacier and we can infer when the ice was last present.

As part of BRITICE-CHRONO people are collecting hundreds of samples from all over Britain and Ireland. Guided by the BRITICE work, they are sampling features tied into different stages of the death of the ice sheet. The goal is to build up a large and robust dataset to understand how quickly the ice sheet shrank.

To the sea

When the ice sheet was there, sea levels were much lower (because the water was in the ice) and the ice left many traces on what is now the seabed. BRITICE-CHRONO is using geophysical techniques to understand the distribution of glacial sediment on the seabed (sometimes on land too). Collecting cores from the sediments on the seabed also provides samples for dating. Cores from far offshore contain large rock fragments. These show that floating icebergs melted overhead, dropping stones scraped from land that became entombed within the ice sheet. Marine fossils offer their own special insights.

There is a lot of interest in understanding features on the sea-bed – construction of offshore wind-farms requires better knowledge of what is out there. Also we now understand the potential for archaeology under these shallow seas. The British-Irish ice sheet may be long dead, but that doesn’t mean people never saw it1.

Recreating the ice sheet ‘in silico’

We know a lot about the world in which the last British ice sheet died. Ice from this time still exists, buried deep in the central parts of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. It contains bubbles of air that once blew over a colder world. From this and other evidence, we have a good record of the climate spanning the period in question.

Scientists have built up sophisticated computer models of how ice sheets grow and die, in part based on research in Antarctica. Take known parameters, such as climate and topography and its possible to recreate an ice sheet ‘in silico’, to build up layers of ice within a computer and watch them disappear as the climate warmed.

BRITICE-CHRONO will build up a robust 4-D dataset of how the ice sheet retreated over time. Combining this with computer modelling will create a positive feedback, increasing our knowledge of how ice sheets behave, both in the past and the future.

Scientific Aims

BRITICE-CHRONO will test three main hypotheses, all of which are relevant to the goal of predicting the fate of modern ice sheets:

- The portions on ice close to sea level collapsed rapidly (in less than 1000 years) but the rate of decay was slower for ice on land. Just how catastrophic was the death of the British-Irish ice sheet?

- The main ice catchments draining the ice sheet retreated synchronously in response to climatic and sea-level change. Was the retreat of the ice controlled entirely by external factors, or did the response vary over the ice sheet? This helps us understand the significance of local rapid retreat of ice in Antarctica. Does seeing it in one place necessarily mean it is happening to the whole ice sheet?

- The volume of ice-rafted debris depends on changes in ice sheet mass balance. Finding large stones in layers of offshore sediment is a direct record of where melting icebergs were found in the past. How is this linked to changes in the ice sheet? Does the amount increase when ice sheets grow, or when they retreat?

BRITICE-CHRONO is less than half way through its 5 years so it is too early to draw any conclusions. The goal is to produce a robust set of data so individual dates will not be published until the full picture is know. Last year saw a massive sampling effort that will continue this year. Although the focus is dating, put experts in the field and they will find new features such as a whole new suite of moraines in Scotland.

The consortium has a blog and is active on Twitter so you can join me in following their progress as they bring an ice sheet back from the dead.