Precambrian rocks are fairly uncommon in England so I jumped at the chance to visit some with the friendly folk of Reading Geological Society. They were found in Charnwood Forest.

The pattern of rocks in England and Wales is broadly one of younging to the south east. A journey from London to Anglesey takes you backwards through time from the ‘Tertiary’ to the PreCambrian visting all the intervening geological periods. Charnwood Forest, near Leicester in the English Midlands is a reminder that this is a simplification. Only 50 miles to the north, in the Peak District, there are many kilometres thickness of Carboniferous sediments. Older rocks are far below. In Charnwood however, there are no Carboniferous rocks – later Triassic sediments sit directly on top of Precambrian rocks.

I haven’t gone all Instagram on you – it was a misty morning at Morley Quarry. The smooth rock face at the bottom is made of Proterozoic (latest Precambrian) volcanic sediments and the reddish lumpy layer is of Triassic age. The line of unconformity is a gap of over 300 million years.

On a geological map, the older rocks appear as little blobs within a red sea of Triassic sediments. This is a sign that an ancient landscape is preserved in this area. We often think of unconformities as planar structures, but this one formed on land and preserves the bumps and jiggles of an ancient landscape. Later folds and faults complicate matters, but the pattern of rocks now is still affected by the ancient landscape.

For example the highest point in the area, Beacon Hill is made up of Proterozoic sediments. It was a hill in Triassic times as well – younger sediments sit in valleys below that are both ancient and modern. There are signs of the Carboniferous landscape here as well. As you might guess from the name, in nearby Coalville there are substantial Carboniferous deposits, sitting between the Proterozoic and the Triassic. The Charnwood forest area during the Carboniferous was likely land close by a water-filled basin filling up with sediment (and coal). All these traces allow us to peer through the mists of time at these ancient landscapes.

To the rocks. Beacon Hill contains good outcrops of the old fine-grained volcanic rocks.

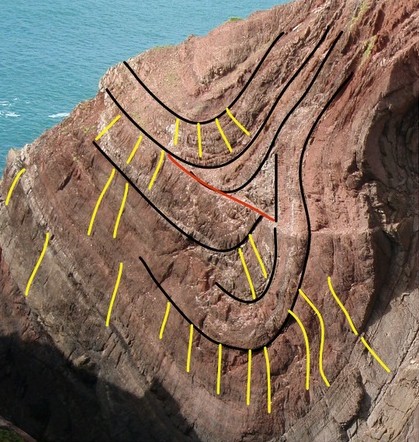

A typical outcrop shows fine beds. The rock is now tilted and hardened by subsequent events. It shows a vertical cleavage as well, formed during the final closure of Iapetus.

The layering is mostly even, but does contain small folds, as you see below.

We also visited Charnwood lodge, which contains coarser volcanic sediments, deposited closer to the site of eruption.

Originally described as volcanic bombs, the fragments here are angular and deposited by debris flows.

Blocks are of andesitic composition, here with some trace of flow banding.

The rocks contain a pronounced cleavage, as you see above.

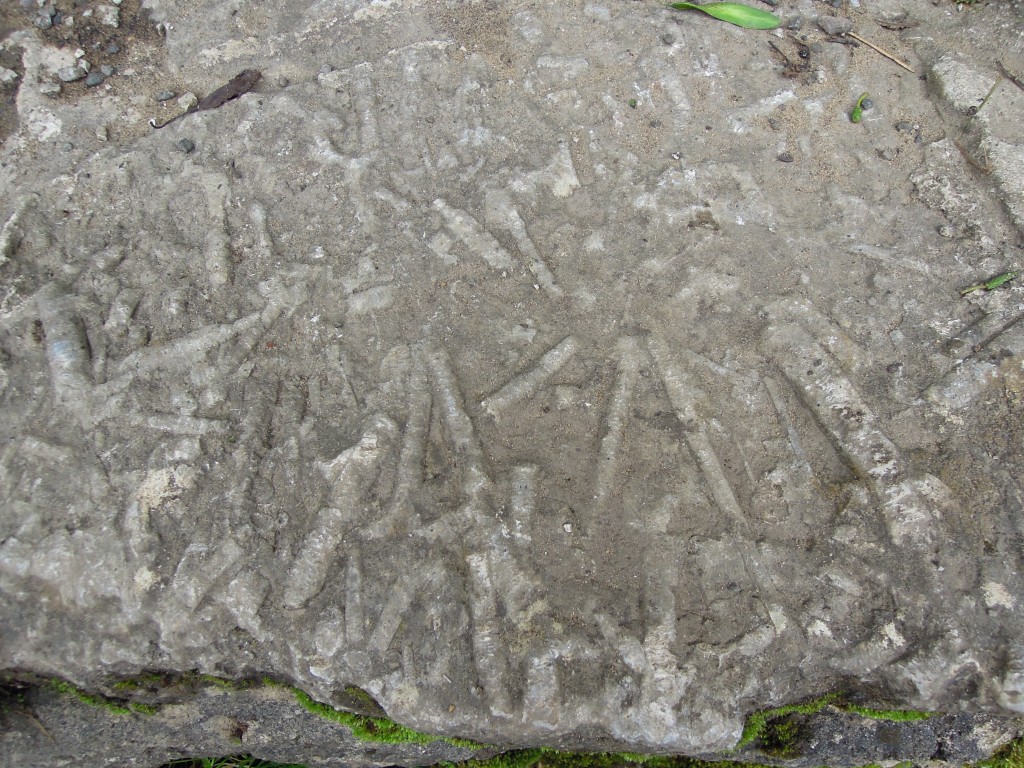

Although they are Precambrian, some rocks in Charnwood Forest contain fossils, subtle outlines of soft-bodied animals that look like plants. In 1956 a local schoolgirl called Tina Negus found the fossil pictured above. Sadly when she spoke to her school geography teacher, he followed ‘common knowledge’ and flatly denied the possibility that she had found a fossil in these ancient rocks, so nothing came of her discovery. A year later, Roger Mason a local schoolboy, found the same structure. Luckily he spoke to Trevor Ford, a geologist, who recognised it for what it was, a fossil, very rare and similar to others found in Ediacara in Australia. He wrote it up as Charnia masoni. Roger Mason went on to be a professor of Geology, with a focus on metamorphic rocks.

There is a moral to this story – truth in Geology resides in the rocks, not in books.