There’s an immediacy to the study of the Quaternary (the last few million years) that is rather seductive. Most geology is (after John McPhee) studying ‘the former world’ but the Quaternary is close enough in time that it is still this world, capped by ice and full of familiar animals and human beings. We can study this period of time in tremendous detail using things – piles of sand, the pattern of the landscape, peat bogs – that are unlikely to be preserved in the geological record.

An outcrop of Irish gabbro tells us about conditions deep within the earth, but the mountain range, even the continent it formed in are all gone. The smooth shape of the outcrop and its covering of fine scratches were caused by the scraping of stones in ice, part of a massive icesheet that stretched across the British Isles. The ice is gone but it flowed over this hill, down that valley. On a chilly day it can feel like it only just left.

Stone moved by ice

One outcome of the great ferment of ideas in 19th Century Britain was the recognition that much of the northern British Isles were once covered by of thick sheet ice. One of the earliest recognised forms of evidence for these vanished ice sheets is found in the form of glacial erratics. These are pieces of rock, sometimes very large, dumped by the ice. The most useful sort come from a distinctive rock type, a granite intrusion perhaps, that allows you to know precisely where the erratic came from and so infer which way the ice was flowing. On the Yorkshire coast in England there are erratics from Norway1, showing that the ice flowed across what is now the North Sea.

Volumetrically the biggest record of glaciation is glacial drift. This is sediment that was moved and ground-up by the ice. It is a very jumbled, poorly-sorted sediment, with big blocks mixed up with sand and silt. If you find a sediment like this, you know there has been glaciation. This applies to ancient sediments just as much as recent ones.

Studying drift, people realised that things were quite complicated. A single place might have multiple layers of glacial drift separated by more normal sediments. They realised that term ‘Ice Age’ is a simplification; this was phenomena that pulsed. Outside of the Polar regions, the ice caps came and went many times, dancing in time with the stately precession of the earth’s axis.

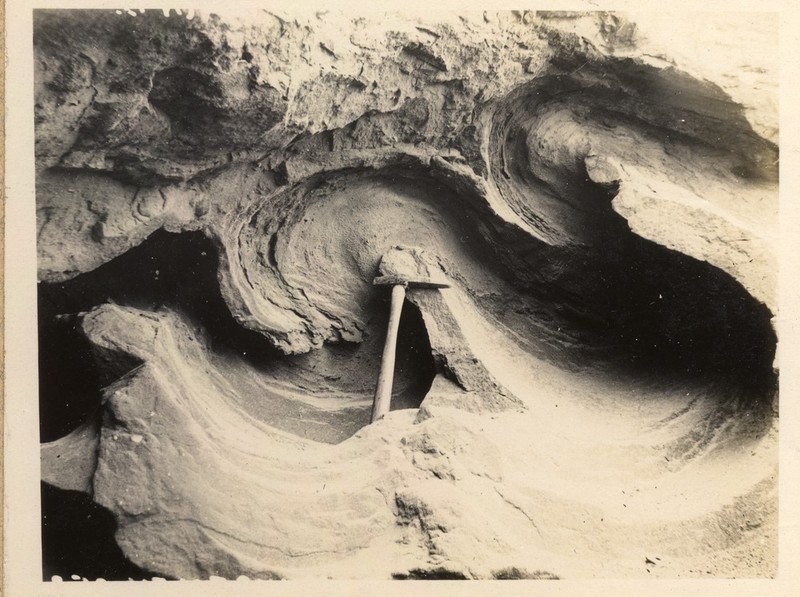

Isoclinal folding in glacial sand and clay. Photo from 1921 courtesy of British Geological Survey. P249721

Sometimes, soft drift gets pushed around by advancing ice. Sometimes this results in beautiful folds, other times it puts sediments containing marine shells deep inland. 2. For this reason, the presence of drift is fairly uninformative. To make firmer conclusions about the most recent advance of Ice, we must turn to more subtle features.

Fainter traces

Glacial sediments aren’t laid down in thin even layers, but in various ways, both elegant and ugly. Valley glaciers often have moraines: piles of sediment at the end or sides that fell out of the melting ice. The same principal applies to Ice Caps, such as covered most of Northern Europe and North America. Successive belts or ridges of moraines can record the retreat of an ice sheet.

Drumlins are piles of glacial sediment that have been moulded by ice flow. They are very beautiful features, with an aerodynamic shape. They can look like the back of a huge whale, somehow rising out of the ground. Often found grouped together, their shape indicates the direction in which the ice was moving when last it was flowing.

A pod of Drumlins swimming in Clew Bay, Ireland. Photo from chrispd1975 on Flickr under CC.

Glacial striations and polishing are common features found on land that was once under the ice. Stones in the ice slowly scratched their way across bed-rock. Asymmetric features known as roche moutonnée tell us the direction of ice flow.

A flock of Scottish roche moutonee (ice flowed to the right). Image from British Geological Survey P008317

A common experience when walking one of the bigger mountains in Britain is to start in a valley filled with glacial till, perhaps with some moraine visible. Next a climb up a ridge shows lots of polished rock. Finally, the summit pyramid is covered in a great thickness of loose stone3. Between this summit block field and the scraped stone below is the trim line that captures the top of glacial erosion. Map out trim lines on multiple mountains and it tells you something about the vertical extent of the ice4.

Summit block field of Glyder Fawr in Wales. Image courtesy of British Geological Survey. P222636

When ice melts, it turns into water. In my gin and tonic this is fine, but when the melting ice is 100s of metres thick, it will have a big impact. Around my home town of Macclesfield in England there are glacial lake deposits. They are sitting above the edge of the Cheshire Plain – there’s no way you could have a lake there today. The only way to explain this vanished body of still water is: it was dammed by the ice.

Other evidence of water flowing in odd ways if found in glacial meltwater channels. These look like small stream beds, but they have no stream today. Sometimes they flow along slopes or uphill for a time -evidence that when the water was flowing, the ice was still around.

If you were building a dam to make a huge lake and you proposed making it out of ice, you wouldn’t get far as an engineer, because at some point the dam will fail and all the water will come flooding out. This happened with melting ice in several places. The huge scoured landscape of the channeled scablands in Washington State, USA, are the biggest example, but my favourite is the Jutulhogget or ‘Giant’s Cut’ in Norway.

Jutulhogget Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Of limited scientific use, but rather beautiful, iceberg keel marks are more evidence for glacial lakes.

Aerial view of glacial keel-marks from near Manitoba, Canada. Square lines are roads: see here for more details

To the science

Knowing about these features really enhances your view of the world – it gives you a way to read landscapes and discover a world of ice so close in time we can almost touch it. But the best thing about these features is that they tell us about the now-vanished ice. Modern researchers have mapped them to track the ice’s ebb and flow. They combine these maps with computer modelling, insights from active ice sheets and techniques for dating so advanced that they seem almost magical. Their goal is to predict the future. In the face of a changing climate, an ice-cap died in Britain 15,000 years ago. Understanding this process better may help us predict that fate of earth’s remaining ice caps. I’ll write more about this next….