Some place names describe the shape of landscape. South east of Lochinver lie Cnoc a Mhuilinn (“Mill Hill”), Gleann Sgoilte (“Cleft Glen”) and Gleannan na Gaoithe (“Windy Glen”). These are dramatic features where the land has been cleaved, leaving narrow slots where the wind howls and narrow fast rivers make mill streams.

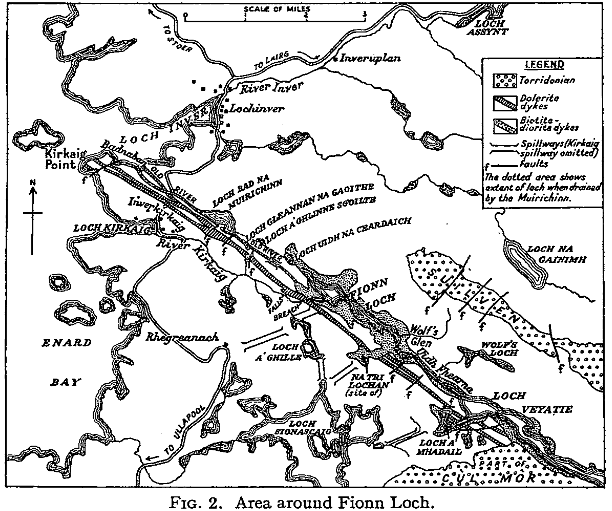

These dramatic features are all aligned in space. How did they form? A paper from 1956 maps them out and links them to a now vanished lake they call ‘Loch Suilven’. Using “an

ex-R.A.F. bubble-sextant in conjunction with a box-sextant“, Alex J. Boyd of Inverkirkaig carefully mapped the fossil beaches left behind by this Loch. From this work it is clear that water levels were once much higher. He inferred that the lake once drained via our dramatic glens, until the modern Inverkirkaig river breached the lake and drained it, separating it out into Fionn Loch, Loch Veyatie and others.

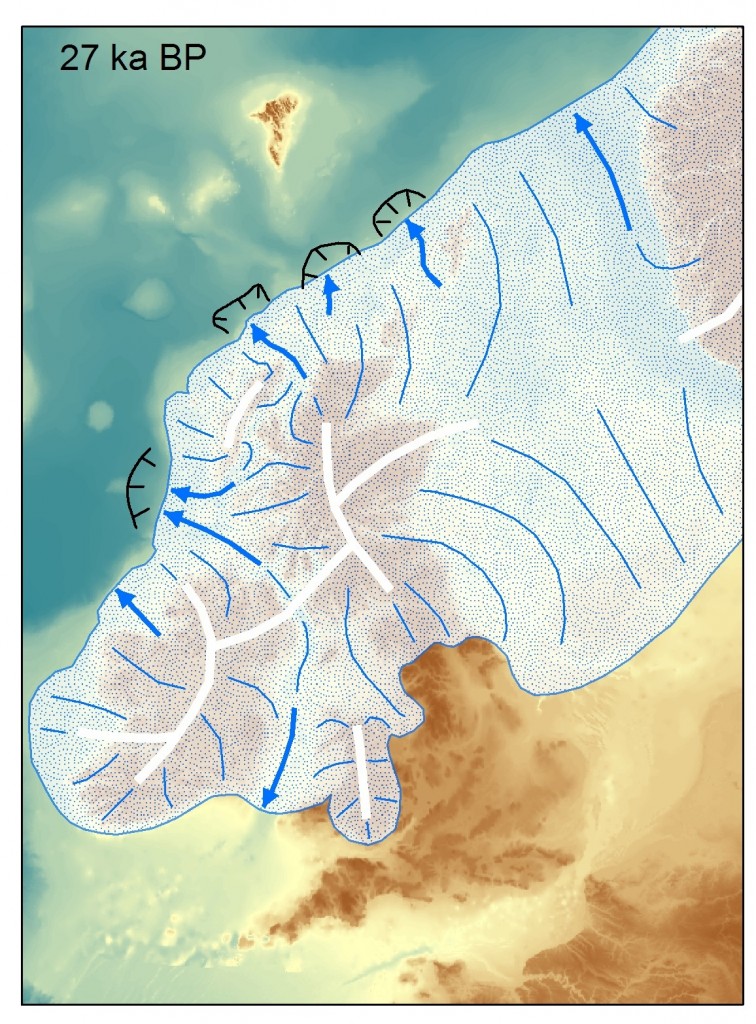

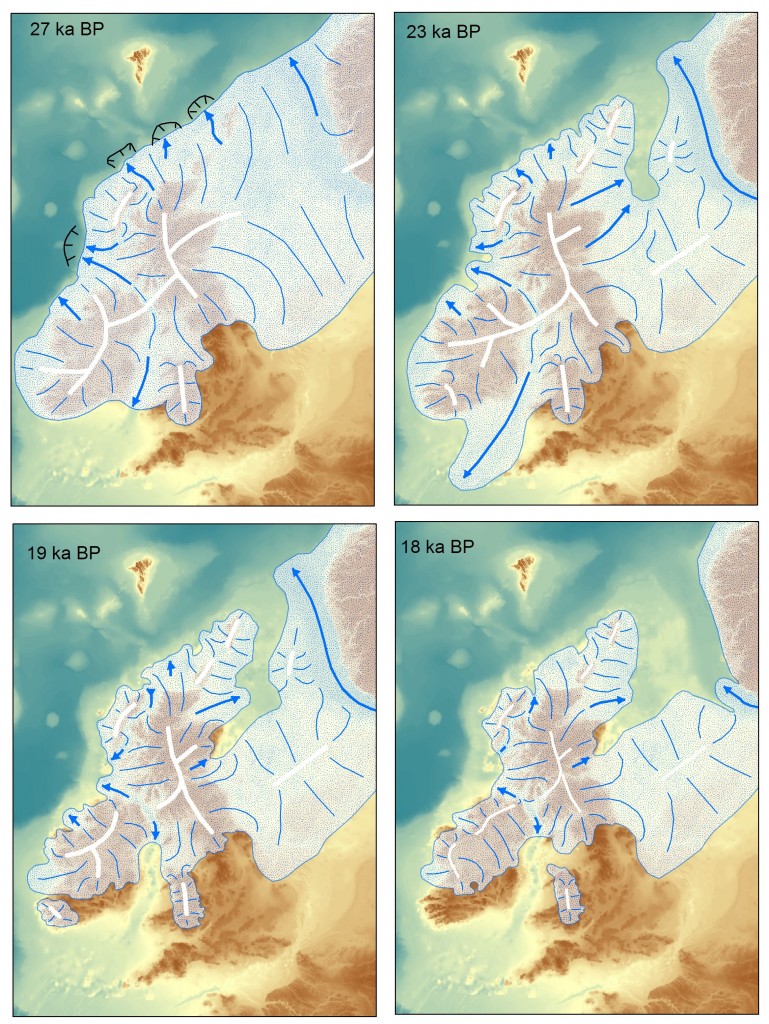

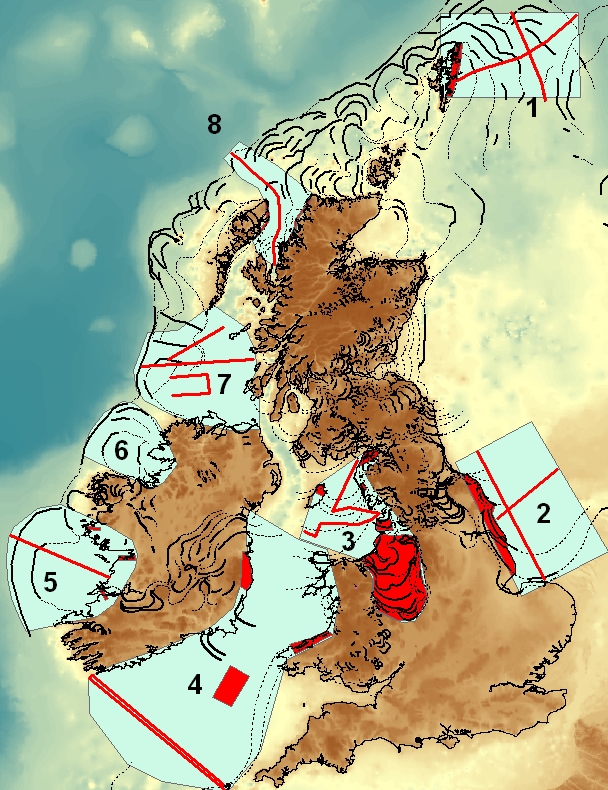

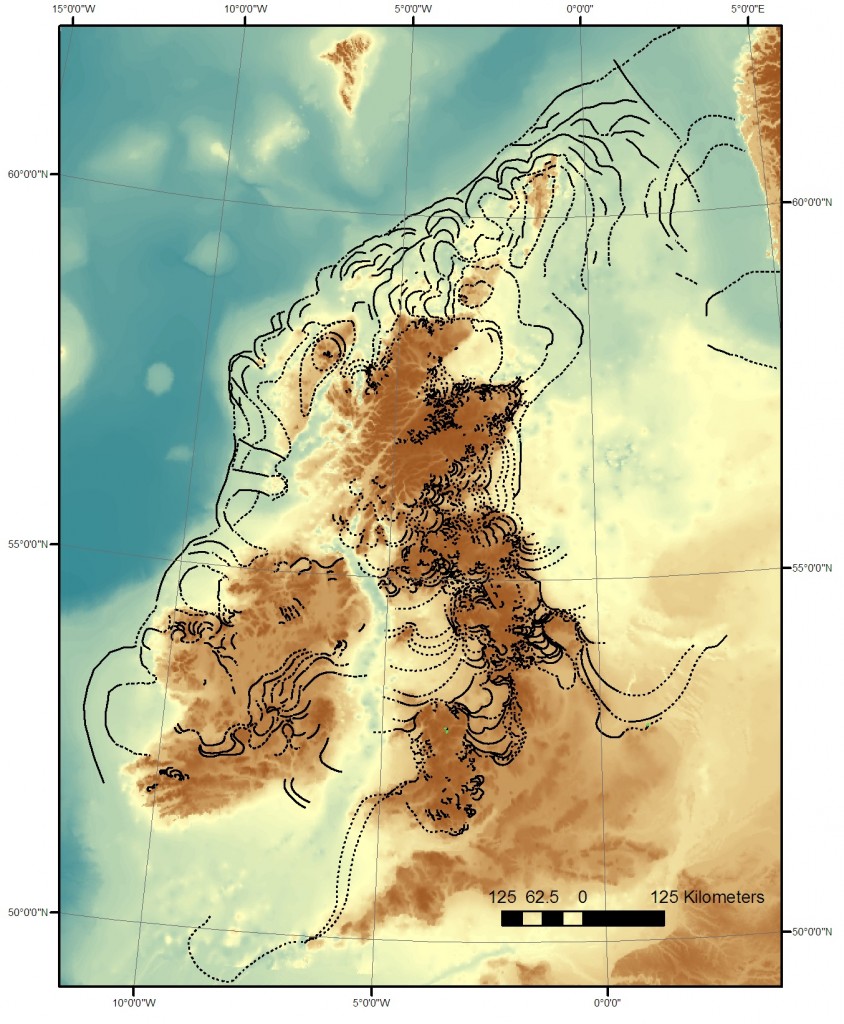

The picture is complicated by ice. This landscape is haunted by the Ice Age and any carving into the ground could have been done by ice as well of water. Glacial melt water channels are features formed by the flow of ice close to glaciers. Water beneath may flow under pressure, or ice may dam rivers, or melt suddenly to create large volumes of water. Under these conditions, channels may be cut by catastrophic flood events.

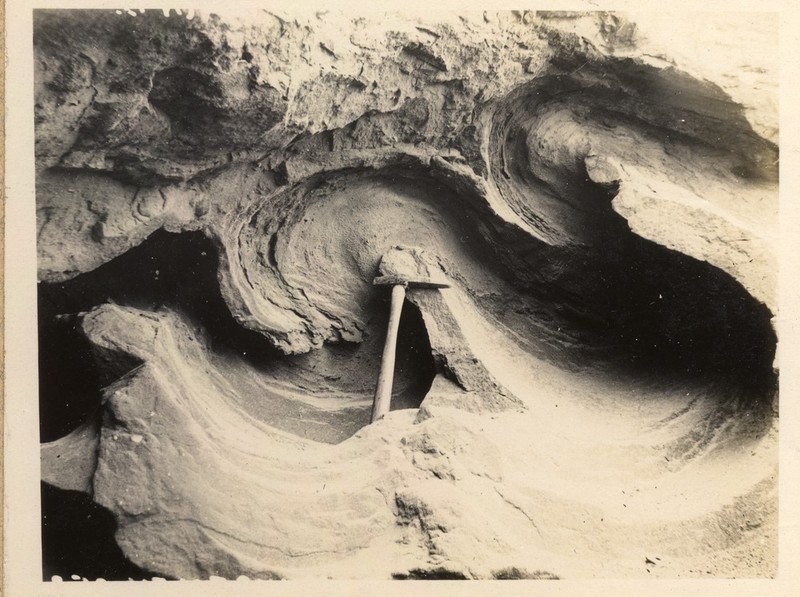

Tracing the western edge of the area, around Badnaban (place of the women) Boyd reports “rounded boulders” of large size that suggest the water flow was of “torrential character”. High up, the walls of the channel below Cnoc a Mhuilinn have a polished appearance with scalloped shapes. The British Geological Survey interpret these as S-forms and P-forms and call the structure a glacial meltwater channel.

A brief scan of modern literature suggests that there is no consensus about the precise meaning of these features, but for sure they are consistent with a dramatic flooding event scouring out the channels. Ice flow may also have shaped the glens and both mechanisms may have acted at different times. But maybe what was eroded is more important than how it was done.

The sculpture within the block

There’s a quote attributed to the sculptor Michelangelo, to the effect that the sculpture is already there within the block of marble, his job is merely to remove the material surrounding it. For this landscape, this may be literally true. We’ve talked of ice and water cutting into the ground, but maybe the most important features were already physically present within the bed rock, waiting to be revealed.

The cnoc and lochan landscape is an extremely distinctive feature of Lewisian gneiss areas. A similar landscape exists in Connemara on the deformed igneous rocks of Roundstone Bog. The writer Tim Robinson describes this landscape as “frightened”. It’s a largely random distribution of lochs and hills, straight lines appearing where it is cut by geological faults, breaks in the rock that weaken it.

Maarten Krabbendam and Tom Bradwell (of the British Geological Survey) have reviewed the cnoc and lochan terrane in Sutherland and conclude that its distinctive roughness is not a direct product of glacial erosion.

They review similar landscapes in other countries and note that they are a feature of rock type, not of erosion style. They compare the Assynt area with similar terrane in Namibia, where erosion is caused by wind-blown sand rather than ice. They show that the shape of the landscape is mostly controlled by chemical weathering, that weakens solid rock into weak ‘saprolite’. The role of erosion, whether scouring by ice or glacial meltwater, is to remove the saprolite, leaving the harder rock behind.

Chemical erosion is highly sensitive to rock type. The Lewisian Gneiss is cross-cut by vertical sheets of rock called dykes. One particular dyke (400 million years younger than the other Scourie dykes) is rich in olivine, a mineral too chemically delicate to last long at the surface. This dyke easily rots into saprolite, forming deep zones of soft rock. The glacial meltwater channel below Cnoc a Mhuilinn precisely follows this dyke; its location was determined not by the ephemeral flow of ice or water, but by events 1,992,000,000 years ago. Gleann Sgoilte was cut into another dyke and Gleannan na Gaoithe formed along a later shear zone, full of fractured and altered rock.

This pattern is common across the whole of Assynt, wherever Lewisian Gneiss is found. These remarkable glens may be more dramatic than most, thanks to glacial floods, but these were simply picking out the bones of the rock. This landscape was etched rather than scraped.