Someone once said: “if you know enough Science, nothing is boring”. I love this idea, but I’m also intrigued by the geographical equivalent: no place is boring, if you know enough about it. Recently I went for a walk to try and find out if this is true.

The walk started from my childhood home in Macclesfield in the north of England. Growing up I could not fail to be aware of living on a dividing line. Down the hill was the town – first school, shops, the train to the bright lights of Manchester, later pubs and the train south to University. Up the hill was the Peak District National Park, open space, hills and geology (I was rock-mad from an early age).

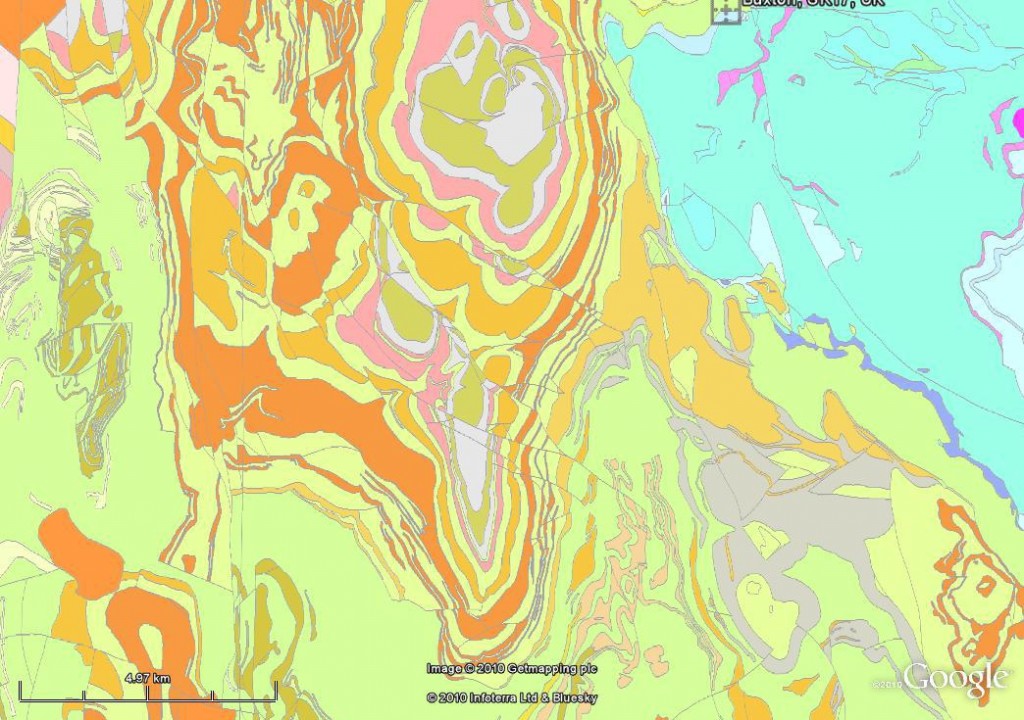

The road down into town crosses a geological boundary – the Red Rock fault. It’s trace is not obvious (it has not moved from a *very* long time) but it is a major boundary. To the west are the red rocks of the Cheshire Basin. They are Permo-Triassic in age – forming both before, after and during the world’s most extreme mass-extinction event. No traces of that here though – the desert environment left sediments containing very few traces of life, even before 97% of the species on earth were killed off. The fault was active during this time, actively making a hole for sediments to fill – a sedimentary basin.

To the east are the older rocks of the Carboniferous, rich in fossils, coal and fine building stone. Go far enough, to Buxton, and you reach early Carboniferous limestone and a tamer landscape, the ‘White Peak’. But my walk sticks with the sandstones and muds of the middle and upper Carboniferous. A bleaker, grander landscape – the ‘Dark Peak’.

My walk started steeply down the road. Just before I reached the canal (I’ll encounter it again, if not directly) I swung back up to the golf club. Here, in the bushes is a reminder of a different era, but one that I lived in: the Cold War.

From my 70s/80s youth I’ve a memory of a distant noise sounding – the minor third intervals you hear in war films during air raids. This was the testing of a siren sitting up the road, on the hill above Macclesfield. It was there to sound the infamous ‘four minute warning’ indicating that nuclear apocalypse was about to be unleashed.

For a few years in the 1960s, if world war three had broken out, there would have been members of the Royal Observatory Corps (ROC) sitting in a bunker near the golf club. Their job was to monitor the various ways in which civilisation was being extinguished. One device measured the electro-magnetic pulse from the initial explosion. Another the house-flattening pressure wave following a little later on. In the following days they would measure the intensity of the radioactive fallout – vaporised cities and short-lived fatally potent radioactive isotopes drifting down from the sky. Those standing above the bunker would get a more visual spectacle – intense but (in several senses) short-lived, with flashes and looming mushroom clouds across most of the horizon

Macclesfield has never been on anyone’s strike list. When my parents were little during World War 2 they heard the sirens sound for real, but few bombs fell nearby. During my youth, if the Russians had ‘dropped the bomb’ it wouldn’t have been on Macclesfield. Manchester to the due North, maybe Warrington NNW, Liverpool NW, Stoke on Trent to the south. Standing on the hill, these are the flashes and vast mushroom clouds that would be visible, Pynchon’s “unbearable sight in the mirror”. My parents, living much of their adult life under the shadow of nuclear annihilation were almost comforted by living on a hill and being in line-of-sight of the vast Manchester conurbation. They would be among the lucky ones – instantly killed rather dying slowly of radiation sickness.

Moving beyond the golf club, you reach the countryside; fenced, managed, farmed, but full of open space and wildlife. There is a northern sky – full of moving clouds, threatening rain but not delivering, a constantly moving shadow-show of sunlight and gloom playing over the landscape.

This section was a favourite childhood walk, down over the Hollins into Langley. The stream, good for paddling, that was our usual destination is smaller than I remember. Of course.

Langley started its life as a mill town – a place conjured into existence by the mechanisation of cloth production (here silk) and the creation of factories (mills) to house the machines. Early factories in the area were driven powered by watermills – a name that stuck, being used also for later coal-powered factories. Leaving Langley round the back of the industrial area (now disturbingly quiet) I passed a reservoir, barely 100 metres long. Surrounded by wooden areas for fisherman to stand on, it resembles a very English form of Coliseum or bull-ring – an arena for man and animal to do battle. Instead of blood on the sand the climax is the weighing and then the release of the fish. Everyone gets to go home for tea, even the vanquished.

Next I cross a small ridge. The map shows Backridges Farm, Ridgehill, Ridgehill Farm, Ridge Hall Farm and Ridge Hill (twice), just in case I hadn’t noticed the ridge. There is tough sandstone underneath and shales down in the lower land below. The landscape is shaped by the rocks underneath – the bones are showing beneath the green skin.

Between the wars my grandfather visited these farms for his job. One farmer told him he had left home for only two nights in his life – to visit nearby Buxton on his honeymoon. Judging by the cars outside, these farms are now lived in by professional couples, thinking nothing of leaving before dawn to fly to a day meeting in Frankfurt or Madrid.

On the way up a long hill slope, I gratefully seize the opportunity to stop and look at something odd. I was on a steep rough path, that was doubling as a tiny stream, yesterday’s rain spilling down it. The water flowed over a patch of something transparent, with little black blobs in it, becoming elongated and a little wriggly. It was frog spawn (or toad) and I had nearly stood on it. Pleased I hadn’t squashed it, I admired the blind optimism that had put it here, far from any permanent stream or pond.

Once I reached the top of the ridge I once again came face to face with The View. It’s not a visual spectacle – it photographs very poorly, unless at extreme magnification. It’s impact is as much visceral as visual, creating an extreme sense of space and scale as the eye sweeps over the whole of the county of Cheshire and beyond into North Wales, Manchester and Merseyside. It is a little like one of those fantastically detailed early Renaissance pictures of fantastic scenes, such as The Garden of Earthly Delights. Pick any part, look carefully and something interesting pops out. Unlike the Bosch picture, Cheshire contains no giant ears holding a blade, but standing at this point in front of the ‘canvas’, you get a fine view of Jodrell Bank. This massive radio telescope was crafted in part from decommissioned WW2 battleships. It is fully directional, so every time you look at it it’s pointing at a different part of cosmos, showing off another side of its structure.

Turning left along the top of the ridge, Sutton Common tower comes into view. It is a startlingly ugly concrete structure, massively out of scale. As a child I remember being told it was where the TV pictures came from; this was true, but not the full picture. The tower is another Cold War structure, part of a communications spine through England. The towers are robust, not too near towns and in line of sight of each other. The communication was via microwave relay, making it less exposed to Soviet sabotage.

Like the bunker, this a structure built to survive apocalypse. The British government expected the Soviets to drop scores of thermonuclear devices on the western side of Britain, letting the prevailing winds spread fallout over the entire country. During the 1950s and 60s, the government was still actively planning how government could continue even after apocalypse. Slowly, however the focus turned away from ‘passive’ defence to ‘active defence’ – maintaining a nuclear deterrent.

Up close the tower is buzzing with masts and dishes, covered with an accumulation of civilian devices, like technological lichen. Countless conversations are whizzing through the air above.

On the top, near the tower I got a shock from on an electric fence which plunged me into a morbid frame of mind. We survived the Cold War – death from above never came. But are we like the frogspawn down the hill? My boot missed it, but it is surely doomed despite that near miss. It’s need for resources grows and grows, yet the conditions around it could change at any moment, snuffing it out. Is modern civilisation the same, nurtured by a temporary river of oil that cannot last for ever? Is there an environmental apocalypse coming that we only dimly perceive (and many of us simply refuse to consider)?

Maybe. But some chocolate biscuits and a look to where I’m going next dispel my gloom. Ahead of me lie traces of thousands of years of human activity and animal traces a hundred thousand times older- evidence of the tenacity of life and the power of human ingenuity. It may be all downhill from here, but for a walker with tired legs that counts as an invitation to live in the moment and enjoy the journey.

The second part of this journey is now available.

The second part of this journey is now available.