Excel is not a database. Even so, spreadsheets are commonly used as such. They are convenient places to enter and store data, but not to get it out again. This post aims to show how using a real database makes this easier.

It uses an SQLite database, which is what many browsers (e.g. Firefox) use to store your bookmarks and history. These can also be read by other software e.g. Geographic Information Systems. It has none of the overly-complex wrappings of MS Access or LibreOffice Base and doesn’t need a server like MySQL or Oracle. Once the data are imported, typically from a comma separated value (csv) file, it simply provides an interface so that we can ask questions using Structured Query Language (SQL).

This example uses the Smithsonian Institute’s Global Volcanism Program catalogue of volcanoes, which can be downloaded as a csv file from their website, as the database. It lists locations and recent eruptions of over 1,500 active volcanoes. Querying the list can generate a wealth of interesting (and less-interesting) volcano facts.

The commands may look complicated at first, but hopefully you can see where the advantages in a real database lie. If so, there are instructions for getting started at the end. If not, just enjoy the trivia.

Get an A-Z list of all the volcanoes in the world.

SELECT "Volcano Name" FROM GVPVolcano ORDER BY "Volcano Name";

| Volcano name |

|---|

| Abu |

| Babuyan Claro |

| Cabalían |

| Dabbahu |

| E-san |

| Falcon Island |

| Gabillema |

| Hachijo-jima |

| Iamalele |

| Jailolo |

| Kaba |

| La Palma |

| Ma Alalta |

| NW Eifuku |

| O’a Caldera |

| Pacaya |

| Qal’eh Hasan Ali |

| Rabaul |

| SW Usangu Basin |

| Ta’u |

| Ubehebe Craters |

| Vailulu’u |

| Waesche |

| Xianjindao |

| Yake-dake |

| Zacate Grande, Isla |

The database contains information on 1555 volcanoes. That’s a big spreadsheet to manipulate by hand. This list is trimmed to give just the first example for each letter of the alphabet. There are 160 volcanoes whose name begins with ‘S’, but only one that begins with ‘X’ (Xianjindo in North Korea).

Get a list of all the volcanoes in Iceland.

SELECT "Volcano Name" FROM GVPVolcano WHERE "Country" IS "Iceland";

| Volcano Name |

|---|

| Snaefellsjökull |

| Helgrindur |

| Ljósufjöll |

| Reykjanes |

| Krísuvík |

| Brennisteinsfjöll |

| Hengill |

| Hrómundartindur |

| Grímsnes |

| Prestahnukur |

| Hveravellir |

| Hofsjökull |

| Vestmannaeyjar |

| Eyjafjallajökull |

| Katla |

| Tindfjallajökull |

| Torfajökull |

| Hekla |

| Grímsvötn |

| Bárdarbunga |

| Tungnafellsjökull |

| Kverkfjöll |

| Askja |

| Fremrinamur |

| Krafla |

| Theistareykjarbunga |

| Tjörnes Fracture Zone |

| Öraefajökull |

| Esjufjöll |

| Kolbeinsey Ridge |

If you wanted to plot them on a map, you can get their latitude and longitude, too.

SELECT "Volcano Name", Longitude, Latitude FROM GVPVolcano WHERE "Country" IS "Iceland";

| Volcano Name | Longitude | Latitude |

|---|---|---|

| Snaefellsjökull | -23.78 | 64.8 |

| Helgrindur | -23.25 | 64.87 |

| Ljósufjöll | -22.23 | 64.87 |

| Reykjanes | -22.5 | 63.88 |

| Krísuvík | -22.1 | 63.93 |

| Brennisteinsfjöll | -21.83 | 63.92 |

| Hengill | -21.32 | 64.08 |

| Hrómundartindur | -21.202 | 64.073 |

| Grímsnes | -20.87 | 64.03 |

| Prestahnukur | -20.58 | 64.6 |

| Hveravellir | -19.98 | 64.75 |

| Hofsjökull | -18.92 | 64.78 |

| Vestmannaeyjar | -20.28 | 63.43 |

| Eyjafjallajökull | -19.62 | 63.63 |

| Katla | -19.05 | 63.63 |

| Tindfjallajökull | -19.57 | 63.78 |

| Torfajökull | -19.17 | 63.92 |

| Hekla | -19.7 | 63.98 |

| Grímsvötn | -17.33 | 64.42 |

| Bárdarbunga | -17.53 | 64.63 |

| Tungnafellsjökull | -17.92 | 64.73 |

| Kverkfjöll | -16.72 | 64.65 |

| Askja | -16.75 | 65.03 |

| Fremrinamur | -16.65 | 65.43 |

| Krafla | -16.78 | 65.73 |

| Theistareykjarbunga | -16.83 | 65.88 |

| Tjörnes Fracture Zone | -17.1 | 66.3 |

| Öraefajökull | -16.65 | 64.0 |

| Esjufjöll | -16.65 | 64.27 |

| kolbeinsey ridge | -18.5 | 66.67 |

What can you tell me about Hekla?

SELECT * FROM GVPVolcano WHERE "Volcano Name" IS "Hekla";

There isn’t room to show all the columns as a table, but the data look like:

Volcano Number = 372070

Volcano Name = Hekla

Country = Iceland

Primary Volcano Type = Stratovolcano

Last Known Eruption = 2000 CE

Region = Iceland and Arctic Ocean

Subregion = Iceland (southern)

Latitude = 63.98

Longitude = -19.7

Elevation (m) = 1491.0

Dominant Rock Type = Andesite / Basaltic Andesite

Tectonic Setting = Tensional Oceanic

Which is taller, Mt Fiji or Mt Etna?

SELECT "Volcano Name", "Elevation (m)" FROM GVPVolcano WHERE "Volcano Name" is "Fuji" OR "Volcano Name" IS "Etna";

| Volcano Name | Elevation (m) |

|---|---|

| Etna | 3330.0 |

| Fuji | 3776.0 |

Fuji wins! But Etna has been trying hard to catch up recently.

What are the 10 tallest volcanoes in the world?

SELECT "Volcano Name", Country, "Elevation (m)" FROM GVPVolcano WHERE "Elevation (m)" IS NOT "NaN" ORDER BY "Elevation (m)" DESC LIMIT 10;

| Volcano Name | Country | Elevation (m) |

|---|---|---|

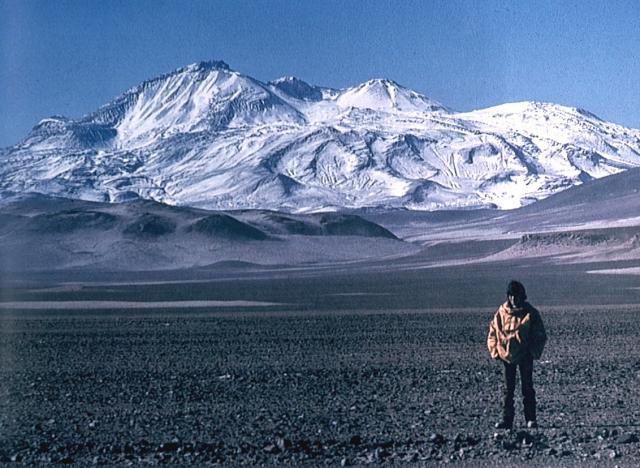

| Ojos del Salado, Nevados | Chile-Argentina | 6887.0 |

| Llullaillaco | Chile-Argentina | 6739.0 |

| Tipas | Argentina | 6660.0 |

| Incahuasi, Nevado de | Chile-Argentina | 6621.0 |

| Cóndor, Cerro el | Argentina | 6532.0 |

| Coropuna | Peru | 6377.0 |

| Parinacota | Chile-Bolivia | 6348.0 |

| Chimborazo | Ecuador | 6310.0 |

| Pular | Chile | 6233.0 |

| Solo, El | Chile-Argentina | 6190.0 |

They are all in western South America. I suppose that this region has the advantage of the Pacific plate being subducted under the South American continent and pushing up the Andes mountain range. The volcanoes just sit on top of it. This highlights the issue that your definition of the tallest may depend on where you are measuring from. Sea level, the Earth’s crust, the centre of the Earth? This video from BBC Planet Earth Unplugged explains this nicely.

Ojos de Salados, on the Chile-Argentina border, is 6888 m tall and last erupted around 700 AD. Source: http://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=355130

What are the 5 northernmost volcanoes in the world?

SELECT "Volcano Name", Country, Latitude, "Tectonic Setting" FROM GVPVolcano ORDER BY Latitude DESC LIMIT 5;

| Volcano Name | Country | Latitude | Tectonic Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unnamed | Undersea Features | 88.27 | Tensional Oceanic |

| Unnamed | Undersea Features | 85.58 | Tensional Oceanic |

| Jan Mayen | Norway | 71.08 | Tensional Oceanic |

| Kolbeinsey Ridge | Iceland | 66.67 | Tensional Oceanic |

| Tjörnes Fracture Zone | Iceland | 66.3 | Tensional Oceanic |

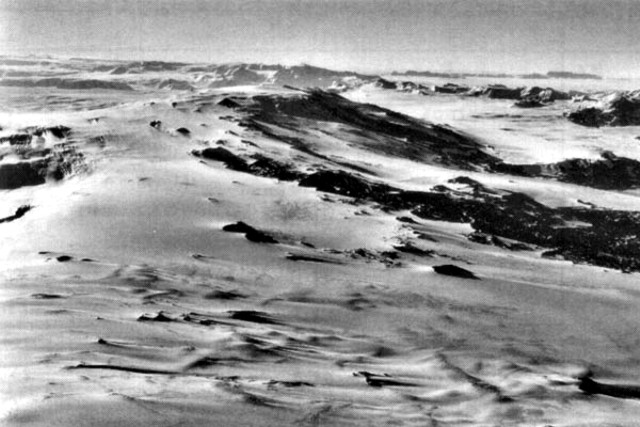

They all relate to the mid-ocean ridges, whereas the southern ones are all in Antarctica and are relate to subduction. There are no active volcanoes within 1,100 km of the South Pole.

| Volcano Name | Country | Latitude | Tectonic Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning, Mt. | Antarctica | -78.5 | Intermediate Continental |

| Royal Society Range | Antarctica | -78.25 | Intermediate Continental |

| Erebus | Antarctica | -77.53 | Intermediate Continental |

| Waesche | Antarctica | -77.17 | Intermediate Continental |

| Unnamed | Antarctica | -76.83 | Intermediate Continental |

Mount Morning, Antarctica, is the southernmost volcano in the world. Source: http://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=390017

What are the most volcanically active countries in the world?

SELECT Country, COUNT(Country) AS NumberOfVolcanoes FROM GVPVolcano GROUP BY Country ORDER BY NumberOfVolcanoes DESC LIMIT 5;

| Country | NumberOfVolcanoes |

|---|---|

| United States | 184 |

| Russia | 154 |

| Indonesia | 142 |

| Japan | 114 |

| Chile | 78 |

If you stood all the volcanoes in the world on top of each other, could you reach the Moon?

SELECT SUM("Elevation (m)") AS TotalHeight FROM GVPVolcano;

| TotalHeight |

|---|

| 2533877.0 |

Not even close! 2,534 km is nothing compared to the 384,000 km distance to the Moon. It isn’t even a tenth as high as the orbits of geostationary satellites (36,000 km).

Which volcanoes have erupted since I was born?

You have to be a little bit tricky with this, as the eruption years in the database are in the form “2013 CE”, so you have to trim off the spare text and tell SQLite to treat it as a number (integer).

SELECT CAST(TRIM("Last Known Eruption", " CE") AS integer) AS Year,

"Volcano Name", Country FROM GVPVolcano

WHERE "Last Known Eruption" LIKE "% CE"

AND Year >= 1979

ORDER BY Year;

| Year | Volcano Name | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Curacoa | Tonga |

| 1979 | Carrán-Los Venados | Chile |

| 1979 | Arenales | Chile |

| 1979 | Lautaro | Chile |

| 1979 | Soufrière St. Vincent | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

| 1980 | Kuchinoerabujima | Japan |

| 1980 | On-take | Japan |

| 1980 | Callaqui | Chile |

| 1981 | Okataina | New Zealand |

| 1981 | Shikotsu | Japan |

| 1981 | Chachadake [Tiatia] | Japan – administered by Russia |

| 1982 | Chirpoi | Russia |

| 1982 | Chichón, El | Mexico |

| 1982 | Wolf | Ecuador |

| 1983 | Colo [Una Una] | Indonesia |

| 1983 | Kusatsu-Shirane | Japan |

| 1984 | Galunggung | Indonesia |

| 1984 | Kaitoku Seamount | Japan |

| 1984 | Mauna Loa | United States |

| 1984 | Krafla | Iceland |

| … | … | … |

| etc. |

There were 273 of them, apparently. The database only lists the most recent eruption of each volcano, so Mt St Helens appears in 2008, and not 1980 in the snippet above. 57 volcanoes registered eruptions in 2013.

How many volcanoes are in the poorest countries of the world?

The real power of SQL comes from combining data from different tables. In this example, we use a list of the countries with Gross Domestic Product per Capita of less than $5,000 from the CIA World Factbook as a filter for volcanically-active countries. If you weren’t just doing this for fun, you’d need to check that all the country names are identical in the two tables.

SELECT COUNT("Volcano Name") AS NumOfCountries FROM GVPVolcano

WHERE Country IN (SELECT Country FROM CIAFactbook

WHERE "GDP - per capita (PPP)" < 5000);

| NumOfCountries |

|---|

| 482 |

So 482 of the 1555 active volcanoes are in the poorest 88 of the 261 countries in the CIA Factbook.

Which countries have the most volcanoes per head?

This example uses a JOIN. JOINs are extremely powerful when you have data of different types in different tables. The number of volcanoes per head is very small, so citizens per volcano is presented here instead.

SELECT v.Country, COUNT(v.Country) AS NumberOfVolcanoes, c.Population, c.Population / COUNT(v.Country)*1.0 AS CitizensPerVolcano FROM GVPVolcano AS v LEFT JOIN CIAFactbook AS c ON v.Country=c.Country WHERE Population IS NOT Null GROUP BY v.Country ORDER BY CitizensPerVolcano ASC LIMIT 5;

| Country | NumberOfVolcanoes | Population | CitizensPerVolcano |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonga | 18 | 120898 | 6716 |

| Iceland | 30 | 306694 | 10223 |

| Dominica | 5 | 72660 | 14532 |

| Vanuatu | 14 | 218519 | 15608 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 2 | 40131 | 20065 |

The join works by matching the Countries column in each of the two tables. Unsurprisingly, I suppose, it turns out that volcanic island nations are the places where people live closest to active volcanoes.

A practical example for geologists

Another purpose of this post is to demonstrate how scientists can benefit from using databases in their work. As a geologist, I need to keep track of samples collected from the field and the results that I get from analysing them. A suitable database might contain the following tables with the following columns:

- Site: Number, Latitude, Longitude

- Sample: Number, SiteNumber, Type (e.g. lava, ash), Description

- XRFData: SampleNumber, SiO2, Al2O3, NaO, K2O, …

The idea is that each table contains only one type of data and that each has one key column with unique values (e.g. site or sample numbers). You can then get your data with short queries.

For example, chemical composition data from the XRF instrument is commonly plotted on a ‘Total alkalis vs silica’ plot, which distinguishes between different magma types (e.g. basalt, andesite). You can extract the data with:

SELECT SampleNumber, NaO+K2O AS TotalAlkali, SiO AS Silica FROM XRFData;

To plot a map of SiO2 content in lava samples you can join the tables together.

SELECT Sample.Number, Site.Latitude, Site.Longitude, XRFData.SiO2 FROM Sample LEFT JOIN Site ON Sample.SiteNumber=Site.Number LEFT JOIN XRFData ON Sample.Number=XRFData.SampleNumber WHERE Site.Type IS 'lava';

If you do more analysis, you can simply add another table (e.g. SieveData, LiteratureData) without having to mess around with the data that you already have and, as long as your sample numbers are distinct, you can keep data from different projects together instead of scattered across many spreadsheets.

Getting started

There are two good programs for viewing SQLite databases. Both are free+open source software, so you can download and install them on as many machines as you like. SQLite Manager is an add-on for the Firefox web browser. It has a nice tool for importing data from csv files. Sqliteman is a small stand-alone package that runs on Linux (sudo apt-get install sqliteman on Ubuntu-like systems), Windows or Mac. There is also a command-line interface utility, sqlite3 that can import and export data.

Click here to download the SQLite file for the database used in this post. It includes data from the Smithsonian Institute’s Global Volcanism Program’s volcano spreadsheet and csv version of the CIA World Factbook from here.

I highly recommend the W3 Schools’ SQL tutorial for learning the language. It takes about an hour. It is also worth reading up on database structure, particularly normalization, to help you choose suitable tables.

Regular readers of volcan01010 may be surprised that I have got this far without mentioning Python, a free+open source programming language that is becoming central to a scientist’s toolbox. The sqlite3 module comes as standard and lets Python read and write directly from / to SQLite databases. The Zetcode SQLite Python tutorial gives a great introduction. It’s often easiest to input and edit data as csv files and it’s straightforward to write a Python script to automatically import them as tables for analysis. As csv files are plain text, they are easily portable and can also be tracked with version control software.

Happy databasing…

I’ve downloaded the volcano sqlite file you provided and have been going through the queries you describe but letters such as ö, ð, or þ in the volcano names aren’t showing up properly. Did you have this problem? I’m using windows 7 command prompt to run SQLite.

Hope you’re well!