Iceland’s most active volcano, Grimsvötn, began erupting last night. Fire and Ice yet again, baby! Here are some answers to questions that you might have.

Why are you so excited?

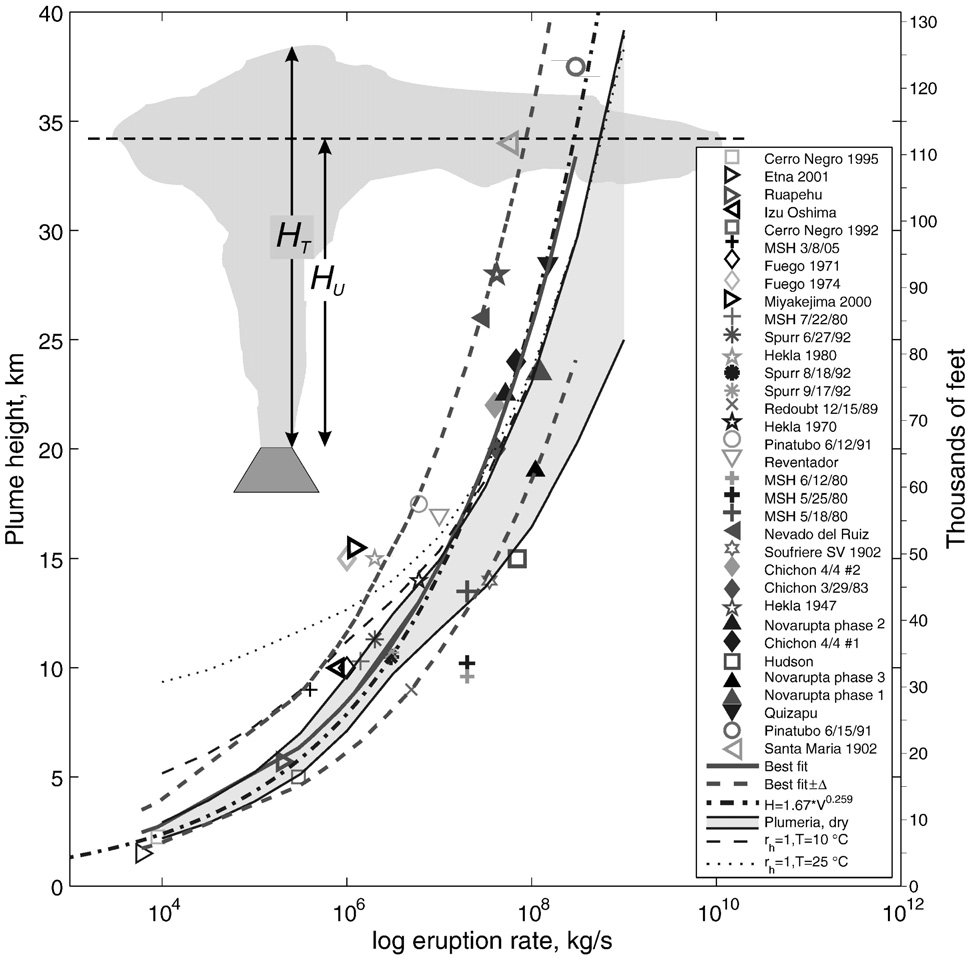

Because it’s big! This is the most powerful eruption in Iceland in over 50 years. Radar measurements, pilot reports and ground observations estimate that the ash-rich eruption plume reached 17 km last night. By comparison, the Eyjafjallajökull plume of last year was 6-9 km high. This is important because every extra kilometre of plume requires a much faster eruption rate. The diagram below, taken from a paper by Mastin et al (2009) compares data from past eruptions.

The diagram shows that an eruption such as Eyjafjallajökull, with a plume of ~7 km corresponds to an eruption rate of 105 m3s-1 (10 x 10 x 10 x 10 x 10, or 10,000 cubic metres per second). This is equivalent to a few hundred tonnes per second in mass. An eruption with a 17 kilometre plume could have a discharge rate of 107 to 108 m3s-1, meaning that it is producing between 100 and 1000 times more material every second. These calculations are obviously only rough, and there are lots of complicating factors such as local weather conditions, the presence of ice over the vent and whether this comparison is even appropriate for the Eyjafjallajökull plume which was not as sustained.

If it’s so big, why is there so little fuss?

The Eyjafjallajökull eruption closed European airspace and cost billions of Euros. This eruption is much bigger, but so far only Keflavik airport (Iceland) is closed and the story is beneath the groundbreaking “Footballer Has Affair” on the BBC front page. The difference in impact on aviation comes down to three factors: the ash being produced by the eruption, the weather patterns blowing the ash around, and new rules about planes flying into ash.

- Fine ash grains fall to the ground much more slowly than big ones, so the distal impacts of an eruption depend on how much fine ash it produces. The proportion of fine ash depends on the composition of the magma, and if it interacts with water (e.g. from a glacier). The Eyjafjallajökull eruption involved sticky, bubbly magma, more than 90% of which formed grains less than 1 mm across. It was explosive when it melted through the glacier, but also once the interaction with meltwater had ended. By contrast, Grimsvötn usually erupts basalt magma, which is rarely explosive by itself and is only explosive now because of the meltwater. The fragmentation is less efficient and the proportion of fine ash is lower.

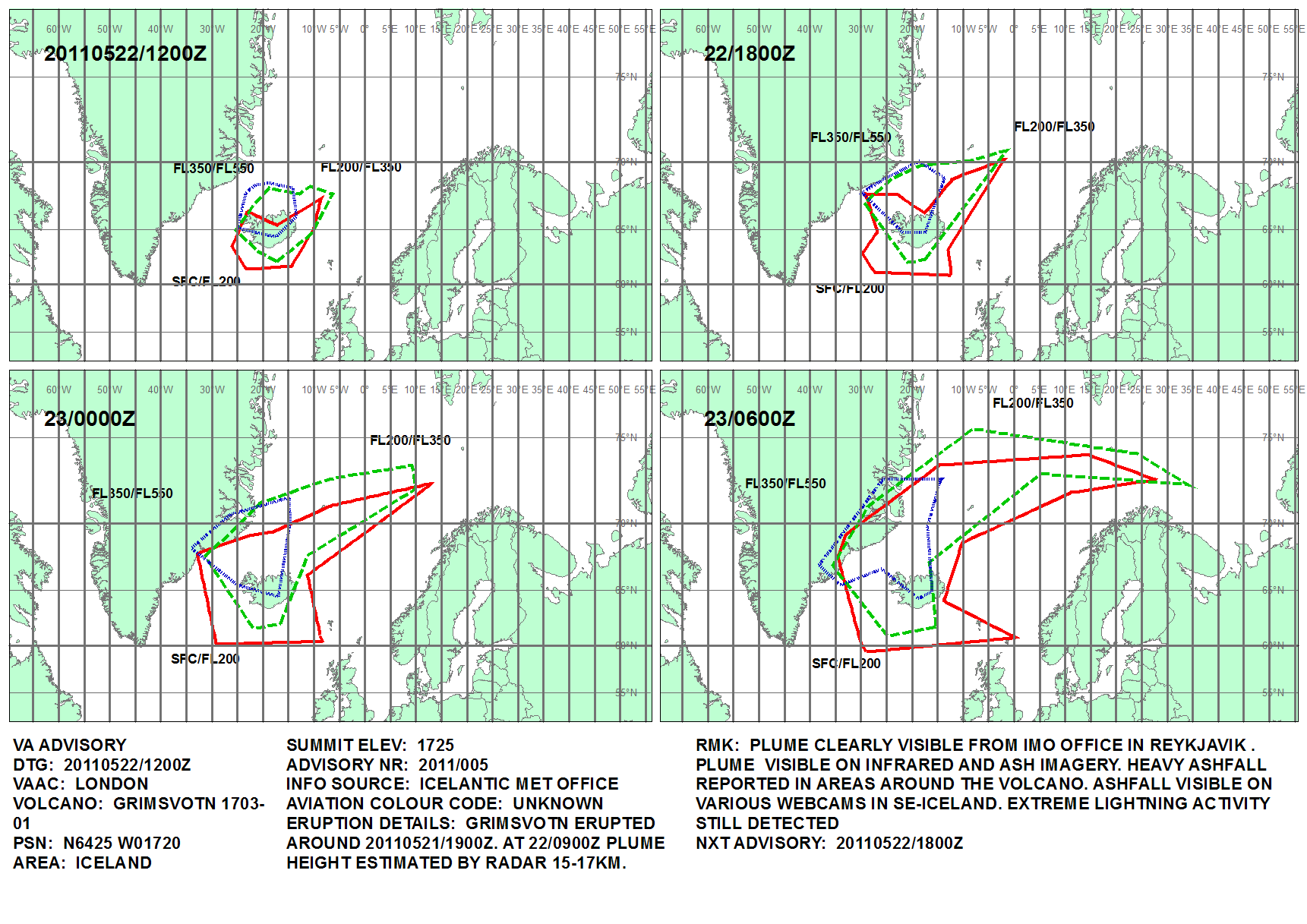

- During the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, there was a high pressure system over the north Atlantic whose northwesterly winds brought the ash right down into Europe. For the moment, the winds are sending the bulk of the ash northwards into the Arctic. The plot produced by the UK Met Office shows the predicted ash dispersion until Monday morning.

- Prior to the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, the rules were that aviation had to AVOID ALL ASH. Now they are different, and where planes can fly is based on zones of different ash concentration. There are real issues with whether we are actually able to measure/estimate the boundaries of these zones with real confidence, but the upshot is that even if we had an exact repeat of the Eyjafjallajökull 2010 eruption, the disruption to air travel would be a fraction of what we saw last year.

So my flight on Wednesday morning will be fine, then?

<<WARNING: SPECULATION AHEAD>>

Not necessarily. Most recent Grimsvötn eruptions have lasted a few days to a week. The most recent one, in 2004, lasted 4 days and erupted the bulk of its ash in the first 36 hours. The Met Office surface pressure chart shows the wind moving to the northwest from Tuesday.

An individual grain of fine ash (<63 microns in diameter), falling from 17 km, can travel 1000 km before it lands, which would take it safely into Scotland. Although Grimsvötn is producing relatively little fine ash proportionally, the much larger eruption rate means that it is still producing a significant amount overall. If the eruption continues, then I wouldn’t be surprised if there were UK airport closures.

We’ll see what happens…

What about local effects?

Iceland is a country about the size of Ireland. For 9 months of the year, you cannot cross the middle as the roads are blocked by snow. Highway 1 is the tarmac ring-road that runs around the country near the coast. The authorities have closed this where it crosses the Skeidarasandur outwash plain in anticipation of a jökulhlaup (glacial flood) when the meltwater escapes the glacier. This means that you can no longer drive directly from Vík in the south, to Höfn in the south east (271 km, about 3 hours). Instead, you have to go all the way round the other way (1068 km, about 13 hours). If the jökulhlaup damages the bridges, then the road could be closed for weeks. Nightmare!

Closer to the volcano, the ash is falling fast. Locals have been told to bring in their livestock and to wear dustmasks and goggles.

Where can I find out more?

- The Iceland Met Office have maps of earthquakes at:

http://en.vedur.is/earthquakes-and-volcanism/earthquakes/ - They also publish tremor (continuous local earthquakes related to the eruption) data for Grimsvötn here:

http://hraun.vedur.is/ja/oroi/grf.gif - Scientific data from geologists at the University of Iceland is here:

http://www.earthice.hi.is/ - The Met Office predictions of the plume location are at:

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/aviation/vaac/vaacuk_vag.html - The wind patterns for the next few hours are available at:

http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/uk/surface_pressure.html - The British Geological Survey have UK-focused information:

http://www.bgs.ac.uk/news/home.html - Internet discussion of ongoing volcanic eruptions commonly takes place in the comments section of the Eruptions blog:

http://bigthink.com/blogs/eruptions

Pingback: Grimsvötn eruption – Iceland’s biggest in 50 years

Pingback: Grimsvötn eruption – a different kind of ash

Pingback: Grimsvötn eruption – could last a week and produce fine ash?

Thanks for the information. So how would we best find out if the Ring Road will be closed over the next several days (website, etc.)? I’ll be visiting next month and will want to monitor problems with traveling.

Hi Steve,

The Iceland Road Administration have a map of road conditions at:

http://www.vegagerdin.is/english/road-conditions-and-weather/the-entire-country/island1e.html

John

Another informative and easily understood post – thanks John. This should make for interesting conversation this week at EAGE.

There was speculation last year that the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull might ‘trigger’ other volcanoes (Katla?) to erupt. Is there any past evidence of Grimsvötn eruptions occuring in relatively close in time to other Icelandic eruptions?

Pingback: World Soccer/Football Latest News & Informations - Barcelona await ash cloud advice

Pingback: Barcelona await ash cloud advice | Latest News in Football

Hi,

Is there an explanation to why it was such a large eruption? Why did it produce 100 to a 1000 times more material per second than Eyjafjallajökull?

Thanks, Jacqui

Hi Jacqui,

I’m not sure, but I would think that this is to do with the plumbing of the volcano, and the volume of easily eruptable magma in the magma chamber. The magma chamber at Grímsvötn is well-established, fairly shallow, and had been filling steadily since the last eruption in 2004.

By contrast, at Eyjafjallajökull, much of the magma was rising up from depth. Some broke through to the surface, producing the basaltic Fimmvörðuháls eruption. Some was injected into the old magma chamber from the 1821-23 eruption, where it mixed with evolved magma there. This produced the explosive summit eruption.

So the long duration and lower eruption rate of the Eyjafjallajökull are probably due to the slow but steady supply of magma from depth, in comparison with rapid supply from a shallow magma chamber at Grímsvötn.

John

Hi John,

You may already know this, but I’m researching Grimsvotn for a paper in my petrology class and thought I’d add to your reply by saying that it’s thought that Grimsvotn is situated pretty near the center of the Iceland Hotspot, which is why it’s currently the most active volcano in Iceland and likely why it’s eruptions are more intense!

Will

In case you’re interested, here is my source:

Gudmundsson, M., and Hognadottir, T., 2007, Volcanic systems and calderas in the Vatnajökull region, central Iceland: Constraints on crustal structure from gravity data: Journal of Geodynamics, v. 43, no. 1, p. 153-169.

I am very sad to hear about the volcanic eruption in Iceland. Very tragic for the people that had to board their flights!

Pingback: Edinburgh GeoHazards