In Accretionary Wege #45 Denise Tang asked for “Geological Pilgrimage – the sacred geological place that you must visit at least once in your lifetime “.

For me, and dare I say it for any British educated hard-rock geologist the answer has to the Assynt district, in Sutherland, Scotland.

Denise asks for somewhere relatively remote and hard to get to. In British terms, Assynt is as far away from ‘civilisation’ as it gets. It is almost at the very northerly point of Britain. From the bits of Scotland where most people live (the Midland Valley) it takes most of a day to drive there. The final part of the journey is on single-track roads that weave their way through an amazing undulating landscape. It is in the bit of Scotland that is more Scandinavian than British – Sutherland means ‘south-land’ in the language of the Vikings, but it is far enough North that I’ve seen the aurora borealis there.

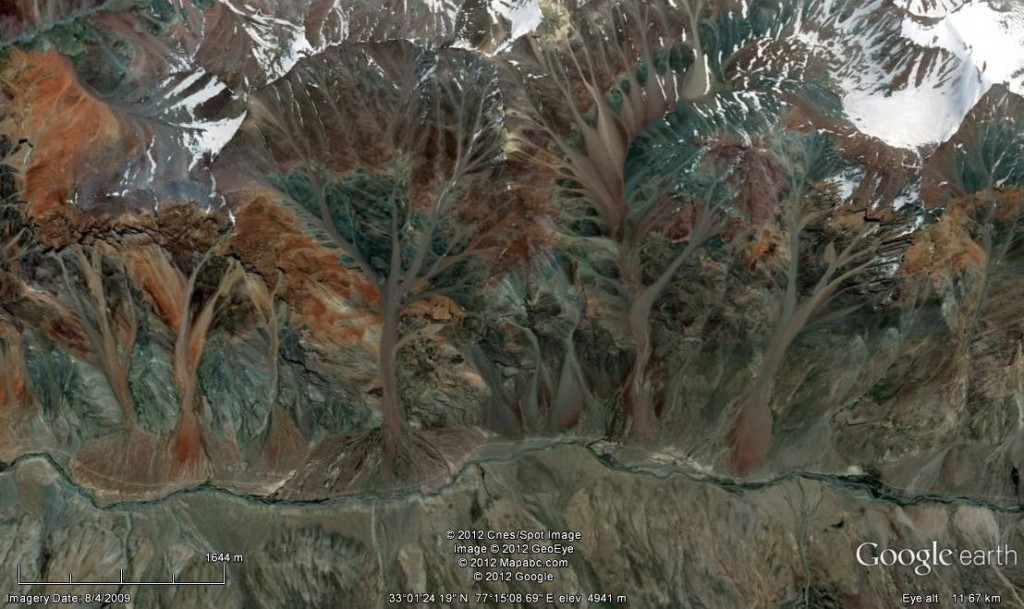

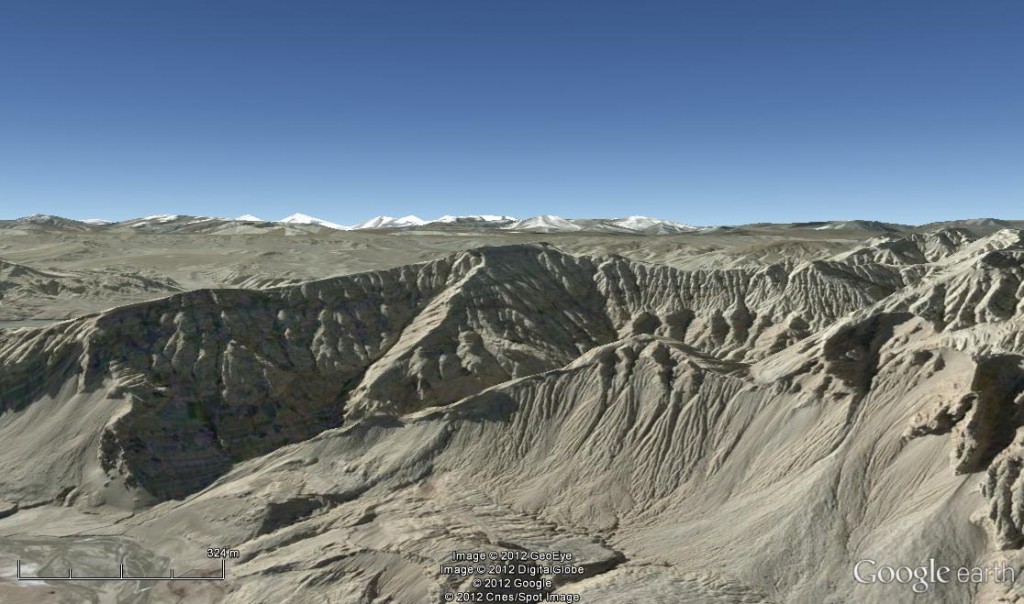

To the Geology. This photo encapsulates the main geological features of the western half of Assynt.

This is the a view of the amazing mountain of Suilven. You’ll have spotted that it is made up of sedimentary rocks – Proterozoic rocks called the Torridonian. These sit on Lewisian Gneiss, Archaean and Proterozoic basement gneisses, visible in the foreground hillock. If you home sits on the the Canadian or Scandinavian shields then these are familiar rocks, but for the British Isles these are exotically old and exotically high-grade.

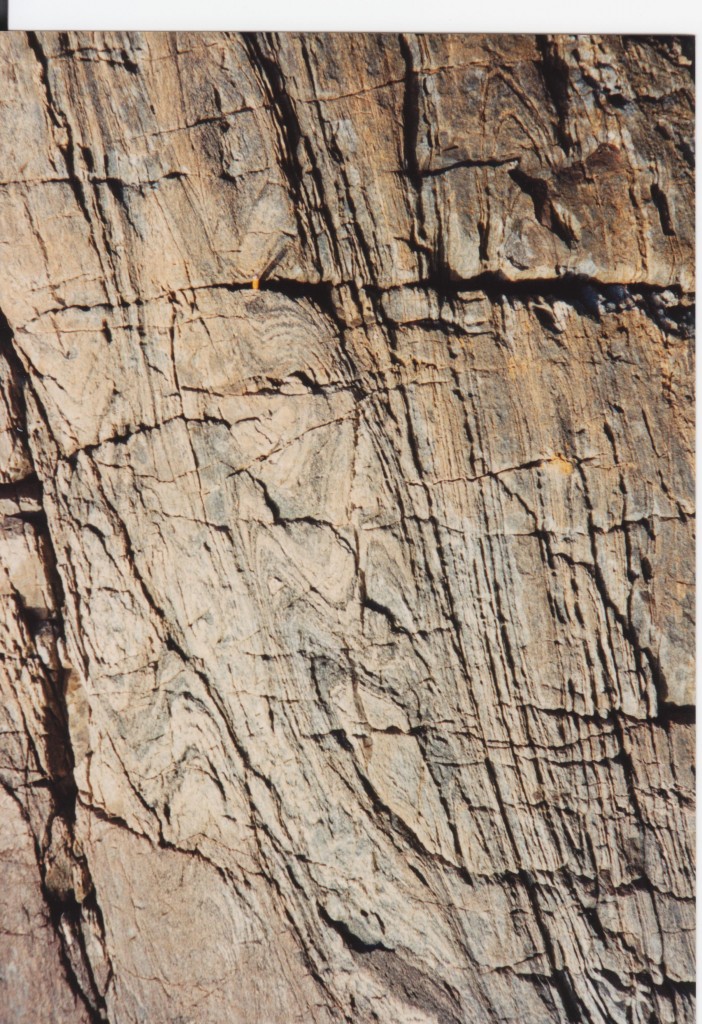

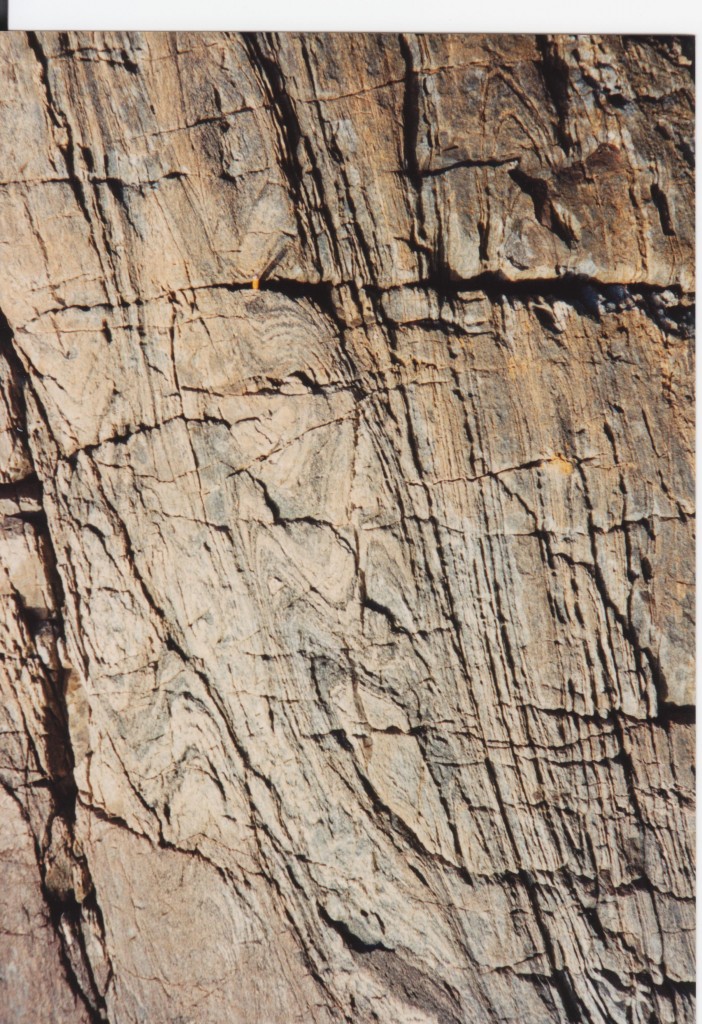

Side view of a sheath fold, Lewisian Gneiss

Intense glacial scouring makes this an amazing landscape. The gneisses form a rugged craggy ‘cnoc and lochan’ landform with lots of little lakes and rock hillocks. The Torridonian forms spectacular mountains (well, hills really) that rise above. In Assynt the Torridonian also includes a layer of suevite, recording a major meteorite impact somewhere nearby.

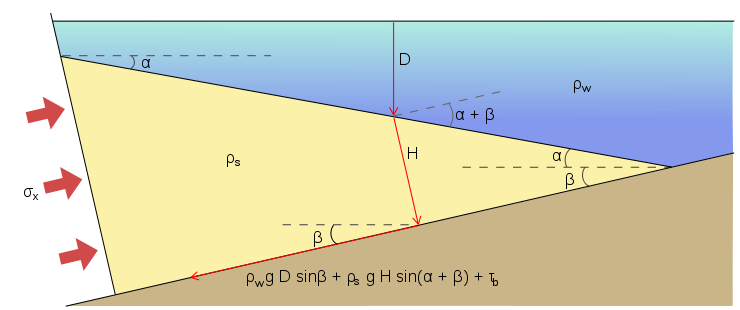

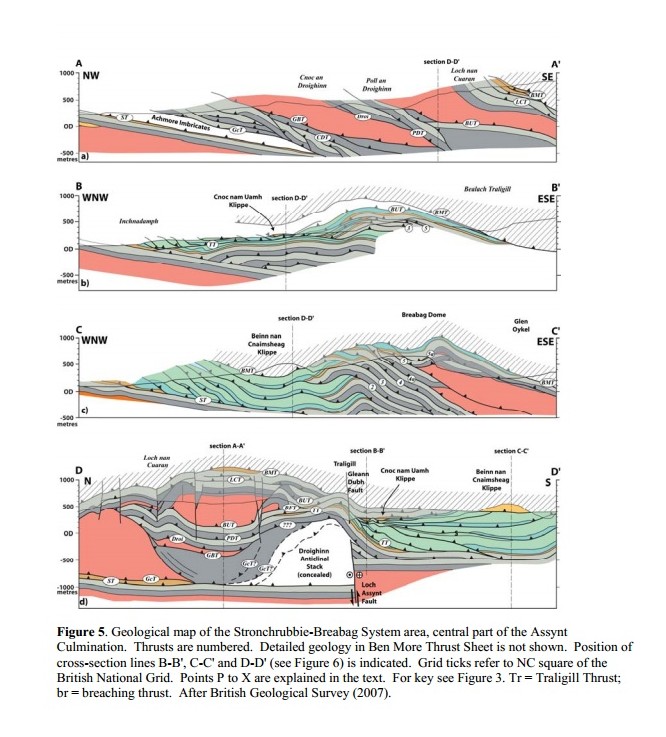

Why should you care about this area? Well, it is a UNESCO Geopark, for one and perhaps the main reason for this is that it contains the Moine Thrust Zone. This is a major thrust structure, marking the edge of the Ordovician/Silurian Caledonian orogeny. It puts the Moine Schists (lateral equivalents of the Torridonian, now strongly deformed and metamorphosed) over undeformed ‘foreland’ rocks. The foreland contains Cambro-Ordovician sediments which sit unconformably over both the Lewisian and the Torridonian. Assynt is a particularly interesting part of the Moine thrust zone as it is a culmination – there is a big package of thrust slices between the undisturbed foreland and the Moine schists. The Cambro-Ordovician sediments are an important part of the picture as they have a regular stratigraphy made up of varied distinctive rock types. This makes the wild structure of this ‘zone of complexity’ much easier to map.

In the early 20th Century, Peach and Horne of the (state-funded) British Geological Survey produced a classic report on the area. This proved without any doubt the reality of thrust faulting and is a significant event in the history of geology as well as a classic of fieldwork. The rock type mylonite (characteristically formed at thrust contacts) was first identified and named (by others) in the Moine thrust zone just north of Assynt.

In the early 20th Century, Peach and Horne of the (state-funded) British Geological Survey produced a classic report on the area. This proved without any doubt the reality of thrust faulting and is a significant event in the history of geology as well as a classic of fieldwork. The rock type mylonite (characteristically formed at thrust contacts) was first identified and named (by others) in the Moine thrust zone just north of Assynt.

As well as showing the complex geometry of thrusting in three dimensions via detailed mapping and copious cross-sections, Peach and Horne also had influential thoughts on the broader tectonic implications of what they found.

In Assynt the ‘zone of complication’ is awesomely complicated. The structure is truly three-dimensional. Well four-dimensional really, as structures cross-cut and debate rages over the sequence of thrusting over time.

Here’s an picture of a relatively simple area (the Glencoul thrust), to give you a taste.

Starting from the base moving up, first you see a hummocky area of Lewisian Gneiss. Then there is a crag of slightly-pinkish layered Cambrian quartzites. There is an unconformity at the base of the crag – it was once a rocky seafloor that became covered in sand. There is a step in the slope and the final rock unit appears – hummocky Lewisian Gneiss again!

The step in the slope marks the position of the Glencoul Thrust, one of the thrust planes that make up the Moine thrust zone. Think about this – all of the upper part of the hillside has been pushed on top of the lower part. If you trace the fault you realise that this would mean 10s of kilometres of horizontal movement. This is an amazing thing. Peach and Horne’s work is important as it settled the matter, proving the reality of thrust faulting, for the first time.

When geologists first starting debating the Moine Thrust, the way Gneiss formed wasn’t understood. Geologists argued that the picture above showed a conformable set of sedimentary rocks. Imagine, if you didn’t know that gneisses aren’t formed on the sea-floor then this makes sense, more sense than the idea of hillsides climbing on top of each other, anyway. Charles Lapworth, who first named mylonite and identified thrusting in Assynt, at one point had nightmares of being bodily caught up in the Moine Thrust, being crushed under what he called the great Earth engine.

You should visit Assynt, if you get the chance, it will give you good dreams, not nightmares. The site of the North West Highlands Geopark will help you plan your visit. While you are waiting, here are some ways to visit virtually. You can get to geological maps of the area via the BGS geology of Britain viewer. There’s an introduction to the Geology on Leeds University’s Assynt Geology website.

If you are as obsessed with Assynt as me, you should buy the centenary Special Publication from the London Geol Soc. It’s not cheap, but it is very large and very good. Portions of it are available on the Internet via the BGS open access repository. Other books include Exploring the landscape of Assynt from the BGS which is an informal guide for walkers and “A geological Excursion guide to the North-West Highlands of Scotland” for a more geology focused guide.

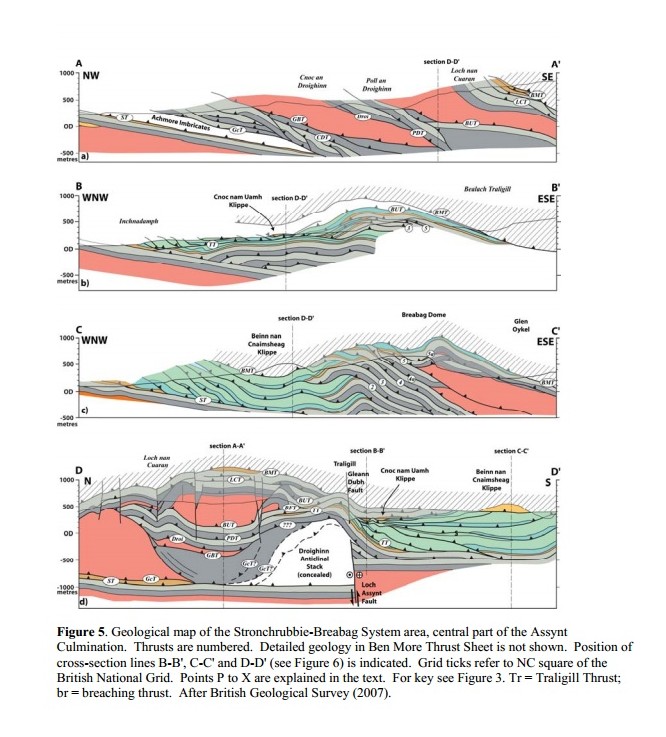

To get a sense of the structural complexity, the paper on the Traligill Transverse Zone by Maarten Krabbendam and Graham Leslie is hard to beat. Here’s a taster of some modern BGS cross-sections to close out with.

Image sources

Photo of Suilven from Neil Roger (neil1877) on Flickr. http://www.flickr.com/photos/neil_roger/4129901847/sizes/l/in/photostream/

Sheath fold picture by the author.

Image of Peach and Horne from Wikipedia

Glencoul thrust picture from Shandchem on http://www.flickr.com/photos/14508691@N08/4818337130/sizes/o/in/photostream/

Diagram from Krabbendam and Leslie with kind permission of primary author. Also thanks to Maarten for information of guide books.