Subduction is just the beginning. Stuck on the surface of the earth as we are, it’s easy to think that when oceanic lithosphere1 is destroyed when it vanishes into the mantle. But this is wrong. The more we manage to peer into the earth’s depths, the more clearly we see that subducted oceanic lithosphere is still down there. It’s arrival into the deep earth influences many things and sets of changes that in turn affect the surface.

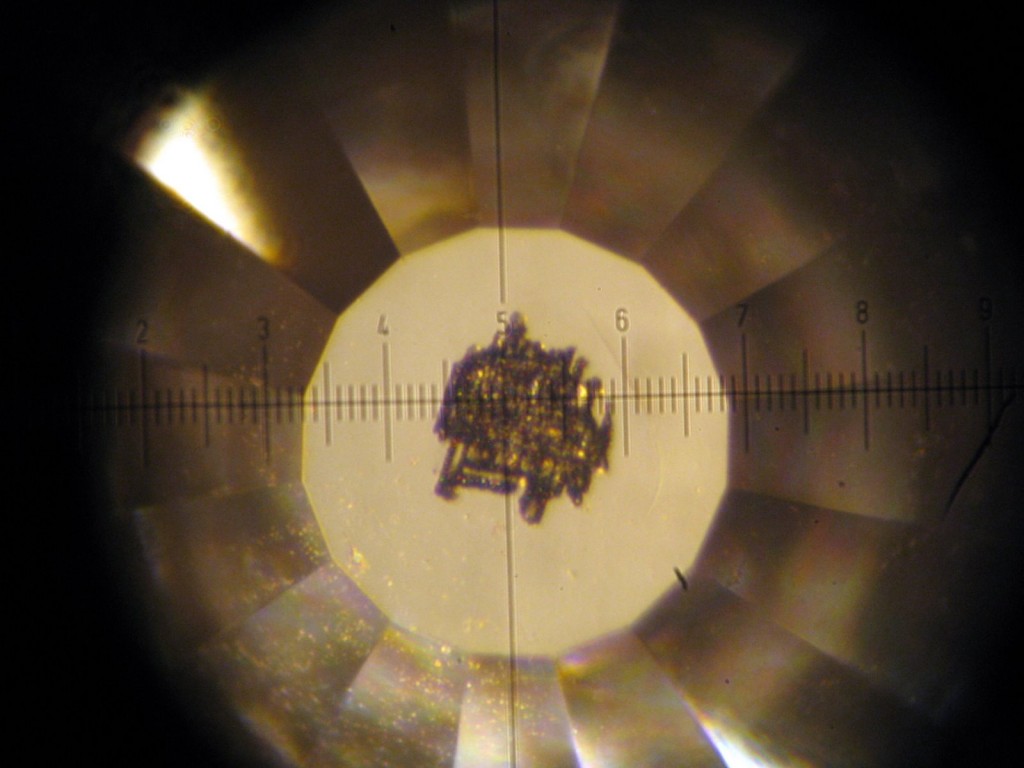

Our growing understanding of what happens to oceanic lithosphere when it reaches the deep earth comes from the integration of a vast repertoire of scientific approaches. Physics, chemistry, mathematical modelling, high-pressure laboratory experiments, tiny grains in diamonds – all these things have something to tell us about the deep earth.

As in the deep oceans, so in the deep earth. We now know that both places are extremely varied environments, warped by extreme pressures, full of the weird and the exotic and some surprising relics from the past. Both are hard (or impossible) to visit, yet they still have influence over surface conditions.

A journey into the deep

This is the first of a series of posts on the deep earth. There’s a great mass of fascinating recent science out there that deserves to be better know. As a taster, let me tell you about lovely little Nature paper from 2005 that picks out the themes I hope to trace through future posts: how much of the deep earth is still mysterious, how we know what we know, the billion-year timescales and how the surface and depths are intimately linked.

In the paper David Dobson and John Brodholt (both, then as now, at University College, London) speculate that some distinctive parts of the deepest mantle are formed from subducted banded-iron formation.

Folded banded iron formation. Photo was not taken at the core-mantle boundary. Image from Wikipedia.

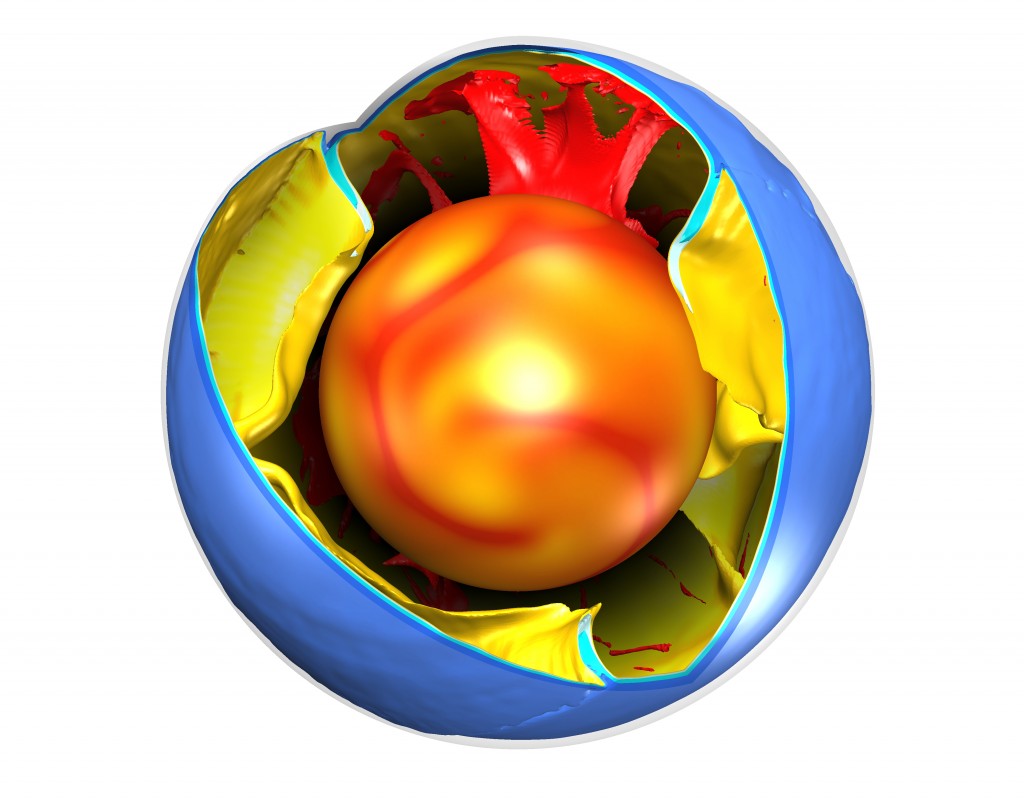

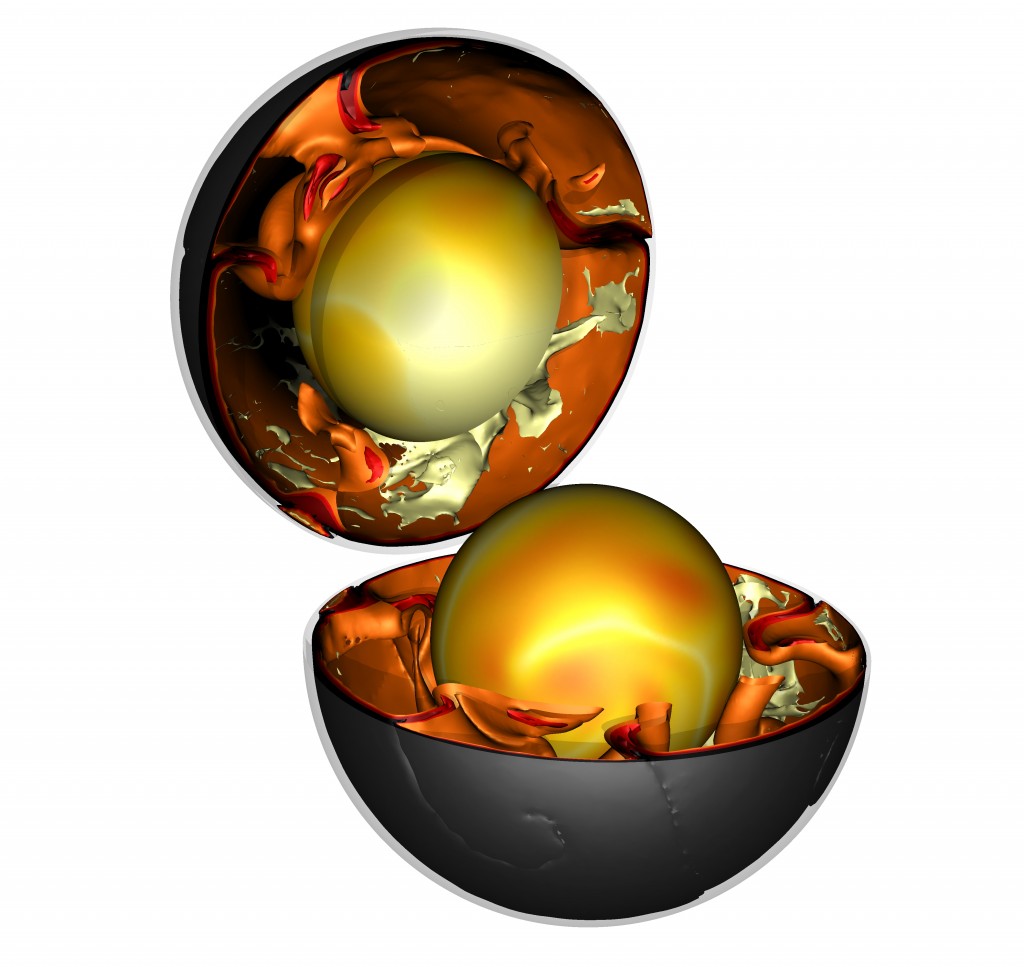

Seismic studies (tracing the shakings caused by earthquakes) have identified parts of the lowest mantle where earthquake waves pass through over 10% slower than expected. This means that these areas, known here as ultralow-velocity zones (ULVZs), must be in some way different – either they are made of different material or they are are at a different temperature to their surroundings.

Nobody knows what the ULVZs are made of, but our authors put the case that they contain large volumes of banded-iron-formation (BIF). Between 2.8 and 1.8 billion years ago photosynthetic organisms (probably bacteria) profoundly changed our planet’s atmosphere by producing vast quantities of Oxygen. One consequence was that ferric iron, dissolved in the ocean, bound with the Oxygen ‘waste’ and was precipitated out as solid minerals of magnetite and haematite. This process created vast volumes of marine sediments rich in iron. These banded iron formation deposits are found in rocks of this age from around the world.

Assuming this material was subducted what would happen and could it account for the properties of the ULVZs at the bottom of the mantle? Tracing through the required steps, our authors show that BIF material would be dense enough to sink to the base of the mantle, able to separate out from the more normal material in the subducted plate and would not dissolve into the underlying iron-rich core. If these steps had occurred, then the material would match the measurable properties of the ULVZs.

Just because something is plausible, doesn’t make it true of course. Proving this link between ULVZs and BIFs definitively may never be possible. But one further clue exists: having an iron rich layer close to the edge of the core might help explain patterns of change in the length of the day we surface-dweller can observe.

The earth’s nutations are daily variations in its rotation. They are caused by the pull of the earth, sun and other bodies, but are also influenced by the degree to which the core and mantle spin independently or are coupled together. The outer core is liquid and the mantle solid, so they would be able to spin independently, but studies of nutations suggest there is some coupling – transfer of momentum – between them. If ULVZs are formed of BIFs and so very rich in iron, they would interact with the earth’s magnetic field causing electromagnetic coupling in a way that matches the observations.

It’s a mind-expanding idea. Sediments formed billions of years ago in a now alien atmosphere sit thousands of kilometres under our feet, subtly modulating the length of the day.

Deep cycles

When listening to a classical orchestra, most often we are paying attention to the high to middling frequency sounds – the violins, flutes and so on. The full experience – a live performance – is vastly enriched by the deepest, lowest frequency instruments. A full desk of double basses, or some bass clarinets make the air itself throb, producing a more physical, visceral and emotional experience2.

Our experience of living on this planet is enriched by our understanding of its cycles of change. The most frequent are most apparent: the year’s seasons; the carbon cycle; Milankovitch cycles that bring ice to sculpt the landscape. Subduction is one of the deepest, the slowest of them all – linking the familiar surface with the mysterious depths, it is the fundamental frequency in the orchestra of the earth.

References

The Nature paper is available here.

Dobson D.P. (2005). Subducted banded iron formations as a source of ultralow-velocity zones at the core–mantle boundary, Nature, 434 (7031) 371-374. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03430