There’s a fabulous new site that shows wind patterns – it gives you a whole new perspective on the globe. One of the most striking things is the regular patterns across the oceans. Until quite recently long-distance travel was dependent on sailing boats, at the mercy of the wind and regular patterns of wind were needed to support regular sailing routes. The goods and people moved by these winds in turn drove dramatic historical changes that still resonate. Let’s look at a few, illustrated by the Earth Wind Map.

Turn of the sea

In the early 15th Century, Portuguese sailors began exploring the Atlantic ocean. Initial footholds were made on groups of volcanic islands: the Azores and the Canaries. Regular travel between these islands and Portugal taught sailors an odd trick: the best route back home was not a straight line but instead a big loop. This ‘volta do mar’ or ‘turn of the sea’ relied on working with the prevailing winds and ocean currents.

Atlantic winds (green), currents (blue) and approximate Portuguese sailing routes (red). Image from Wikipedia.

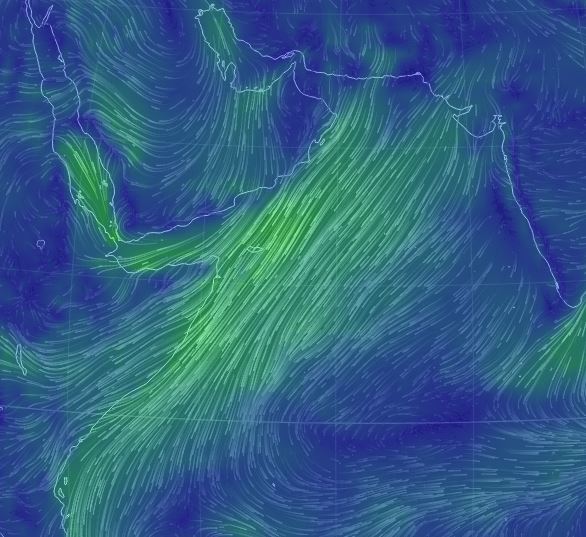

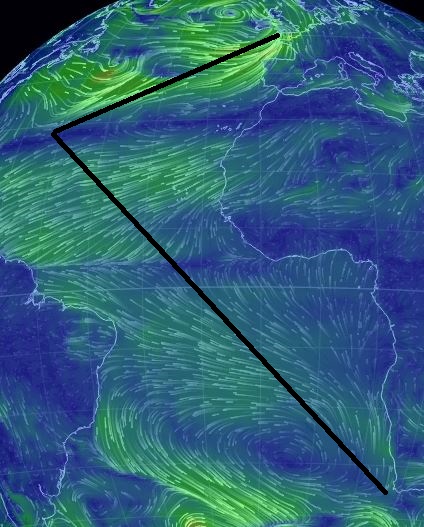

Here’s how the Earth Wind map looked for this area recently: the same pattern can be seen even in this snapshot of actual conditions.

Image captured from Earth Wind Map. With permission.

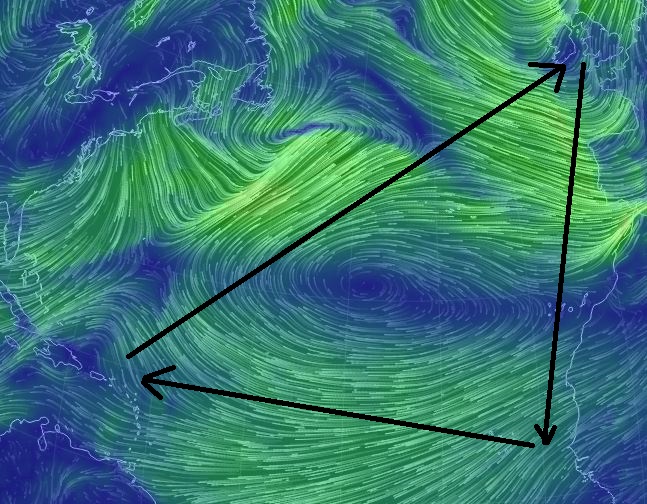

Later sailors showed this pattern to be of global significance. It stretches across the entire Atlantic – Columbus used it on his return from the Americas. Eventually Spanish sailors correctly guessed that it applies to the Pacific, allowing the Spanish empire to connect Central America and the Philippines.

These patterns are caused by global circulation of the atmosphere. Warm air rises at the Equator and flows up and towards the poles. At around 30° latitude (north or south) it descends again into a region of high pressure called the Horse latitudes. Further north a different circulation cell is found, forever whirling in a different direction. These flows of air, on a spinning globe, create patterns of prevailing winds: ‘trade winds’. These patterns are fundamental features of the earth and have been recognised in ancient climates.

Spice

The Portuguese weren’t the first people to sail long distances, of course. Trade across the Indian Ocean between Africa, the Middle East and India was established long before; it supplied the Romans with spices as well as lions and tigers for their circuses.

The northern Indian, like the Atlantic at the same latitude, has trade winds that move towards the south west. This is convenient if you want to speed your cargo of hungry tigers from India over into the Red Sea and via Egypt to Rome. But how do you get a cargo of gold coins to India to buy the animals in the first place? Unlike the Atlantic, the horse latitudes are on-land: there is no turn of the sea to get you east.

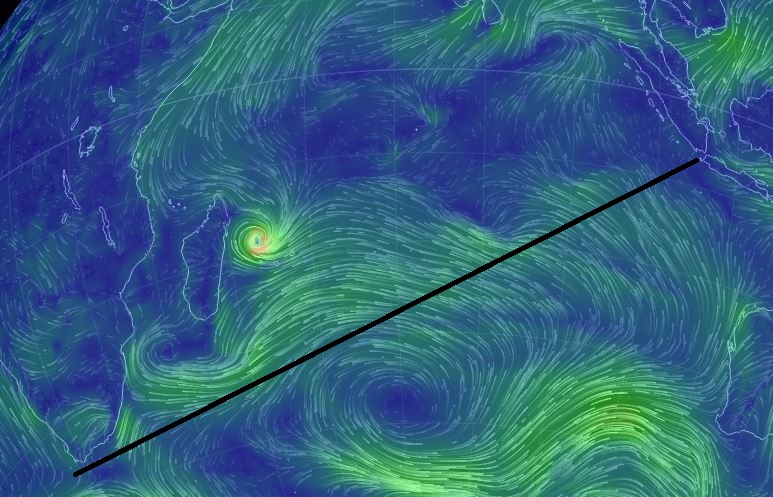

In the Indian Ocean something remarkable happens. The billion year old trade winds are switched, flipped completely round every year. From May until October winds blow from the south and west, towards India. This pattern allows repeat journeys and supports trade. In later centuries these winds sculpted a maritime ‘Dhow culture’ that stretched from the East African coast via Arabia into India.

What has the power to overturn a global pattern of wind? The Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau do. This massive area of high altitude land was formed and is kept aloft by the ongoing collision between Indian and Asia. During the summer, heating of the high land lowers air pressure, drawing in air from the ocean. This reverses the pattern of winds and brings massive rainfall to India, feeding crops that feed millions.

Sugar, gold and blood

European exploration of the Atlantic of course led to the ‘discovery’ of the Americas, a new land full of Silver and Gold and indigenous civilisations collapsing under the onslaught of vicious diseases to which they had no immunity.

For many, the question was: how to make money from this new land? For the Spanish in central and south America, silver and gold was the obvious answer. The Portuguese in Brazil and the English and others in North America and the Caribbean turned to farming, preferably of addictive substances.

Sugar, cotton and tobacco could all be grown in the Americas and shipped west to newly addicted populations in Europe. But who was going to grow the stuff? Shamefully, the answer was slaves from Africa, sold in exchange for rum or textiles made in Europe (from ingredients grown in the Americas). Part of the reason this system worked was to do with the winds. The ‘turn of the sea’ was scaled up into the ‘triangular trade’ that took ships from Europe, to Africa, to America and back again.

In time Europeans realised the full horror of this system. The world’s first consumer boycott was of sugar, first organised in Britain in 1792. They realised that not a cask of this slave-grown sugar came into Europe “to which blood is not sticking”.

Tea

What the British mostly did with sugar was put it in their tea. Until the mid-19th Century, drinking unboiled water in a British city was a good way to die young. The traditional solution to this was to drink beer or gin – both sterile, if not completely healthy. In time, powered by growing commercial power in Asia, tea replaced booze as the British drink of choice (at least during working hours). This thirst drove the last great flowering of commercial sailing ships: the tea clippers.

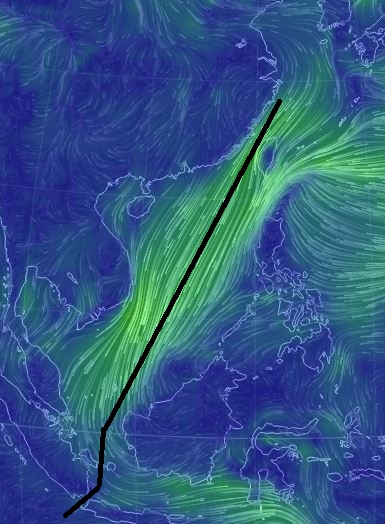

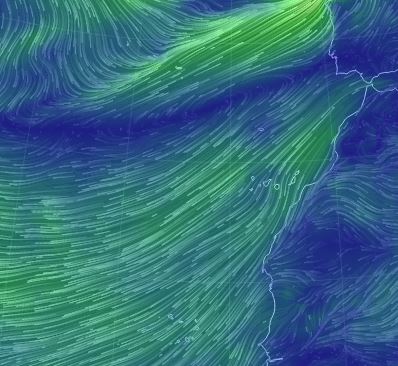

Tea is a seasonal crop and the best tea is fresh tea. For these reasons fabulous beautiful ships were built to speed it across the world. The great tea race of 1866 saw four sailing ships race from China to Britain packed with tea. The first ship to arrive would command the best prices. The route they followed was the fastest possible, drawing on hundreds of years of knowledge of the trade winds. Let’s trace their winding route on a windy globe.