- Pressure-Temperature-time paths

This post is in the middle of a series on metamorphism.

Concepts such as metamorphic facies or grade all allow us to link a metamorphic rock to a particular set of conditions, under which it was metamorphosed. This is a simplification, of course. Hold a piece of schist in your hand: we know that it was once sediment at the earth’s surface and we also know it got back to the earth’s surface again, to catch a geologist’s roving eye. It’s been on a journey. Calling it a greenschist facies rock tells us about a single point on its journey, but not the whole picture. Being romantic souls, geologists often refer to this journey as the rock’s Pressure-Temperature-time path, or P-T-t path. Pressure and temperature are the things we can measure, because we understand how they affect metamorphic reactions.

So how can we discover more about the journey, what is a typical journey and why do concepts such as grade still make sense?

How to create a P-T-t path

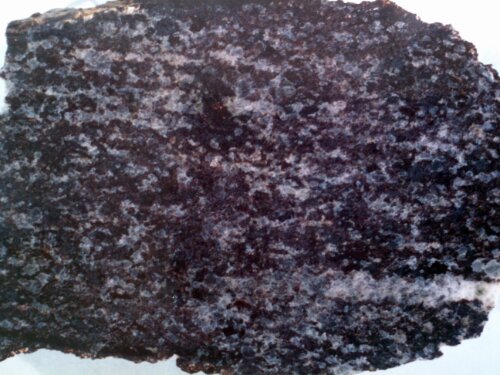

Metamorphic rocks are complicated. Take this beauty from Connemara, Ireland:

The big gray lumps are garnet, the orange stuff is biotite. The big area a third of the way from the right is a sheaf of muscovite, containing yellow staurolite. These minerals tell us its an amphibolite grade rock. Some investigations of mineral chemistry could allow us to quantify that a bit more and put a big cross onto a plot of Pressure and Temperature, representing peak conditions.

There is more information to had from this rock, though. A transect through the garnet would show that the Mn, Fe, Mg and Ca values vary systematically from the core of the garnet to the edge. We know that the garnet would have started small and grown bigger, so the values from the core are earlier than the ones at the rim. The garnet therefore contains a trace of the journey the rock has been on. Often we can infer that the conditions were of lower pressure and temperature when the garnet started growing. So, we can draw an arrow up and along towards our cross marking peak conditions. This arrow we call the prograde path, the portion of the journey before the most extreme conditions.

Look at the lowest big garnet, see the greenish patch just above it? (OK, maybe not, but it is very clear down the microscope). The green is a patch of chlorite, which is associated more with greenschist conditions. Is this another part of the prograde path? No, as the chlorite can be seen as patches within biotite, showing that it grew later. The chlorite is part of the retrograde path, another line we can draw going from the peak conditions back to the surface. We have drawn a P-T-t path.

This is a simple example but I hope it illustrates the general point. The best sorts of rocks for determining P-T-t paths have more dramatic features in them, such as pseudomorphs, where minerals have gone, but their shape remains, or mineral coronas, where a whole new retrograde mineral assemblage was created around the edges of the peak minerals. Also, different samples within a package of rock may preserve different peak assemblages. Put these together and a thorough may allow us to build up a more detailed view of the P-T-t path shared by a package of rocks.

Some types of P-T-t path

Geologists have been creating quantitative P-T-t paths for some time now. What do they look like?

In the roots of ancient (or even active) mountains, Barrovian metamorphism is characteristic.

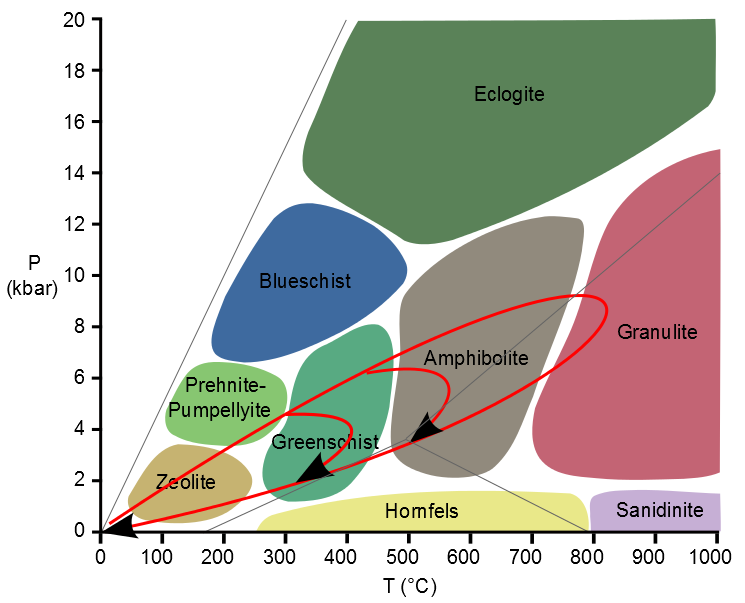

I’ve taken a standard diagram of metamorphic facies and drawn on roughly some typical P-T-t paths. The upper red line is the prograde path, the lower the retrograde. Different rocks reach different peak temperatures, varying from lower grade greenschist rocks up to granulite facies gneisses. This is pattern seen in Scotland and if you read my earlier post, you might think of the lowest temperature loop as the Laphroaig one, the highest as the Macallan.

Rather nicely, if you use mathematical models to predict what happens if you form mountain belts by thrusting rocks sheets over and over, you predict very similar P-T-t paths. Initially pressure is increased faster than temperature, eventually, perhaps because thrusting ceases, the line flattens off as temperature increases (thrusting buries cooler rocks). Eventually a maximum temperature is reached, which is likely where the peak assemblage is formed, as many metamorphic reactions are most sensitive to temperature increases.

Different rocks are buried to different depths, and reach higher or lower grade but they all follow a similar type of P-T-t path. So via modelling based on geophysics, we can now link observations in the field to a tectonic mechanism and explain multiple pieces of evidence. This is proper science.

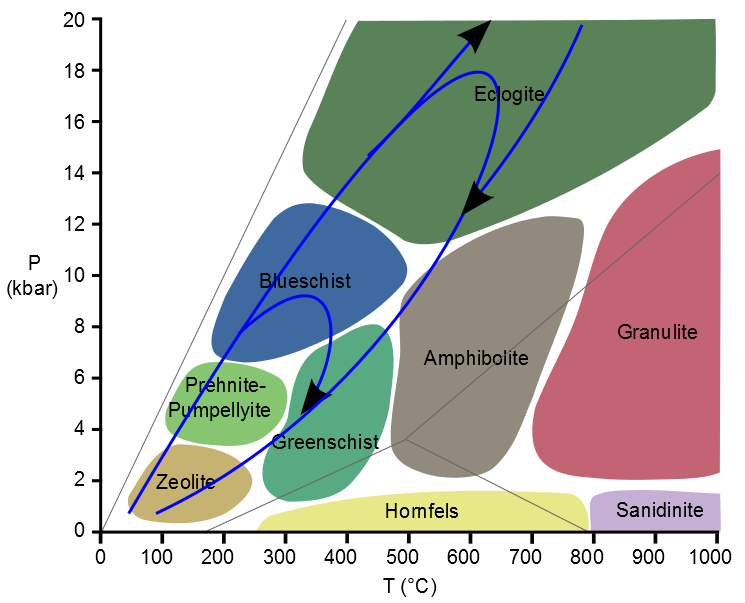

What of subduction zones, where rocks are thrust down to great depth?

Compared to rocks in mountain zones, subduction zone rocks are buried and returned to the surface before they have a chance to heat up. One remarkable aspect is how deep some of these rocks go. In the 1990s, the recognition of the quartz pseudomorph coesite in continental eclogitic rocks from China and Norway demonstrated that they had been buried to extraordinary depths (>70km). This is literally off the scale of the diagram above (* see below). In Norway these rocks are found just below large extensional faults and shear-zones that have sheared sediments on their top surface. The contact is not a sedimentary one, the rocks were exhumed all the way to the surface by tectonic processes. This is a reminder that the retrograde path is not necessarily just a record of slow erosional unroofing, but can have drama and excitement too.

Why is grade still a useful concept?

All metamorphic rocks are unstable; leave them in the rain long enough and they will turn into sediments. Their journey is never ending, but always controlled by their physical conditions, and often by the presence of water.

My example schist above shows a little evidence for the retrograde path, but is dominated by the minerals that grew when it was at its hottest. The concept of metastability is key here. Diamonds don’t grow at the surface and so ‘aren’t stable’. The carbon atoms would ‘like’ to be in the form of graphite, (or to put it another way, this would minimise their Gibb’s free energy). But they are tightly packed into a crystalline lattice and, even on someone’s finger, quite cold. So, at surface conditions, they are metastable.

The peak assemblage minerals in my example schist are like this. They were metastable all the way down the retrograde path. It takes energy to initiate reactions and in a cooling rock, this tends not to happen.

Also my sample schist was likely quite dry as it cooled. Water is very important in metamorphic reactions as a participant in many important metamorphic reactions (those involving devolatilisation). It also is a solvent and can be a catalyst for metamorphic reactions. Atoms can zip around in the fluid phase and so are more likely to find places they prefer, compared to having to diffuse through mineral lattices.

Eclogites are often found as pods within lower grade (blue/greenschist) rocks. Compared with Barrovian rocks, retrogression is more important. This may be because they still contain a lot of water, also the retrograde path passes through more pressure-sensitive reactions. In comparison, a high-grade Barrovian rock has little water left and many of the reactions it is passing through require the addition of water. The retrograde path is therefore much less obvious in the rock.

So now you know. P-T-t does not mean a cup of Darjeeling made from Irish bog water** but instead a reminder that the lump of schist in your hand has been places you’ll never go.

Note * Depth relates to pressure depending on the density of the rock, as the weight of the rock above is providing the pressure. It varies, but 0.25 kbar per km is a good rule of thumb so top of the diagram (20kbar) is about 80km depth. Note that as well as showing the Pressure-temperature diagram in different ways (sometimes with pressure increasing downwards), the units can also vary. The diagram above has kbar, which is kilobars, which is 1000 bars. A bar is 100,000 pascals and is about the pressure of the air you’re breathing. A pascal is a Newton per square meter and is the pukka SI unit for pressure. Therefore we should use pascals (Pa), but since the pressures we are dealing with are so high, we need a billion of them, written GPa for giga-Pascal. A kbar is 100,000,000 Pascals and so 0.1 of a GPa. So a more properly labelled version of the graph above would have 2GPa at the top. Aren’t you glad I left this bit to the end so you could ignore it?

Note ** “peaty tea”. Sorry, I’ll stop now.