There’s a cup of tea next to me, steaming gently. I’ve already written about the history of the drink, how a Chinese herb ended up defining Englishness and having the power to create riots in Ireland. But what of the cup? It’s a posh one – not a thick heavy earthenware mug but a slightly translucent piece of porcelain, strong enough to be made into thin delicate shapes. Like the tea within it’s on my desk thanks to early modern globalisation but it is also a type of metamorphic rock, of anthropogenic facies1 as you shall see.

The cup comes from my granny’s ‘China tea set’. In England, fine elegant pieces of porcelain are associated with China, as that’s where sometime between the 7th and 9th Centuries porcelain was invented. It soon made it’s way along the Silk Road through Central Asia to the sophisticated cities of the Islamic world2. Poor and backward Europe didn’t see much porcelain until we worked out how to bypass the Silk Road by ship.

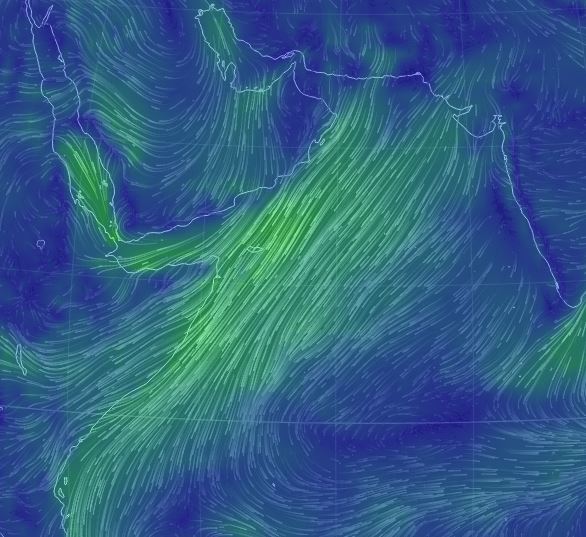

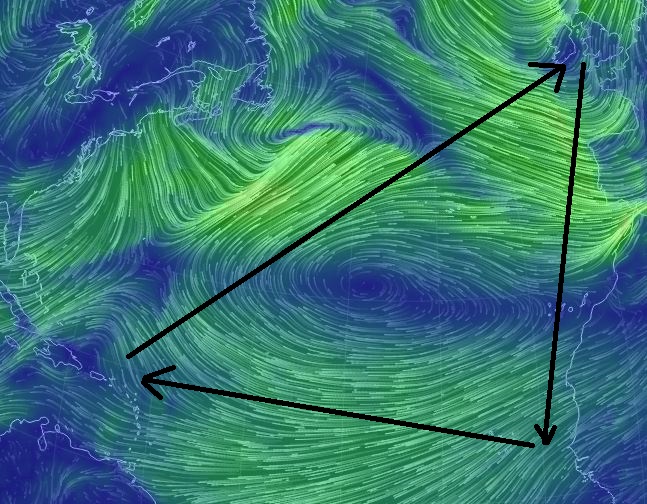

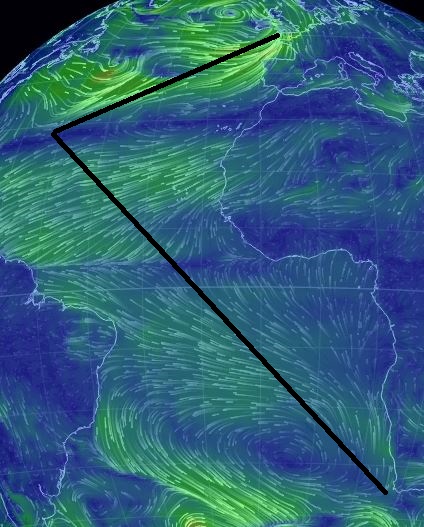

The ships that started the trade in tea with China in the 16th Century, sailed East laden with silver bullion as this was the only thing the Chinese wanted from the West. The silver itself was mostly mined from the South and Central American mines run by the Spanish, but that’s another story.

Ships that swapped silver for tea and silks had a problem. These Eastern luxuries are light and the ships were designed to sail best when sitting low in the water. Needing to add weight – ballast – they shipped back something heavy that they could sell in Europe – Chinese porcelain. Starting with royalty a taste for ‘fine China’ spread across Europe from the 16th Century. In a pleasing symmetry the finest examples were, in Europe, as valuable as silver. This beautiful strong translucent material was used to make plates, bowls, cups, tulip holders….

Porcelain is not the same as ‘earthenware’ or ‘stoneware’ that Europeans were already familiar with. Take most forms of clay and bake them at high temperatures and they form some sort of pottery. Clay minerals have a platy layered structure dominated by a lattice of aluminium and silicon oxides. Water is always to found between these sheets3 but also a wide variety of other elements. Clay minerals form during weathering of other rocks – where water and time break up tidier mineral structures that formed deep in the earth but are less suited to existing at the surface.

When heated, clay minerals break down. The water hidden inside them becomes keen to escape, driving chemical reactions that build new minerals. When a clay-mineral rich rock is buried in the guts of a mountain range, it is transformed into a metamorphic rock – a schist say – where aluminium rich metamorphic minerals grow – micas, Garnet, Staurolite and many more. If you’re really lucky the rock will partially melt, resulting in an migmatite. Taking clay and baking it in a kiln is the same process – a human created (anthropogenic) form of metamorphism.

Human metamorphism is much quicker than the natural form and at much lower pressure, but occurs at a much higher temperature (>1200°C for porcelain). The minerals and textures that form are therefore different, notably the grain size is much smaller. There is also partial melting of some minerals in the clay, which helps to bind the material together. In standard pottery, the clay contains a mixture of different clay minerals so a variety of new minerals form, giving it a generic brown sort of colour.

When Europeans first encountered porcelain, it was like nothing they’d ever seen. Strong, fine and translucent, with a pure white colour. Almost immediately they attempted to copy it. Early attempts involving ground glass and ash from bones. This soft-paste porcelain had the desire translucent quality but was softer. Only in the 18th Century did Europeans manage to produce the real thing, first in Dresden in Germany and then in France (Sèvres) and Britain.

The secret was to start with the right ingredients – nearly pure quantities of a particular clay mineral called Kaolinite (found in kaolin, or “china clay”), mixed with a common mineral called feldspar. Kaolinite – Al2Si2O5(OH)4 – forms from the breakdown of feldspar under the action of hot water. For all three of the early European sites of porcelain manufacture, the kaolin came from granitic rocks4. The English deposits in Cornwall are still being mined- here soon after it formed, the cooling granite pulled in groundwater, heated it and pumped it around, rotting itself from the inside.

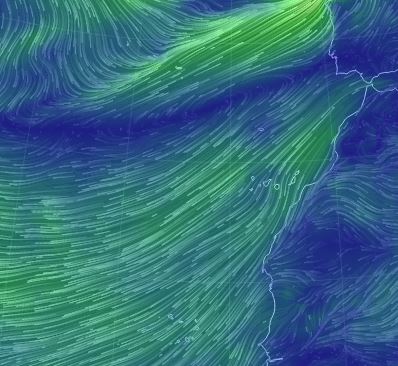

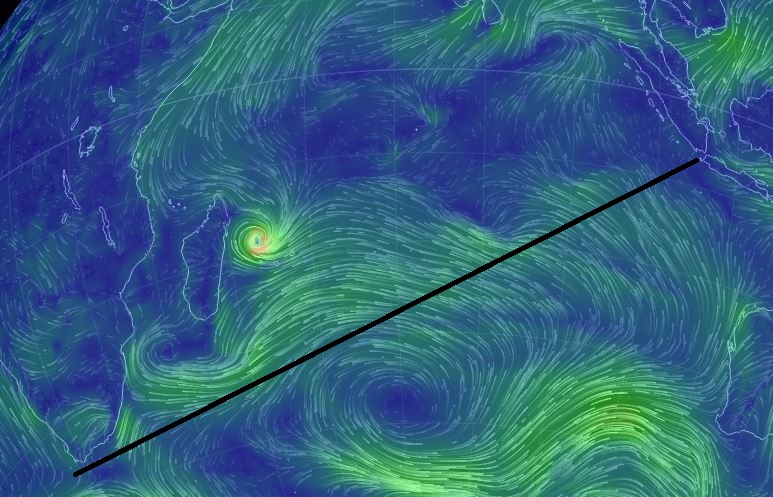

China Clay pits visible from Space in Cornwall. Image from Wikipedia

Just like the progression from mudrock to slate to schist to gneiss, the metamorphic process to form porcelain has various stages5. First the water is driven off leaving a disordered material called metakaolin (Al2Si2O7). Between 900 °C and 1000 °C a new mineral phase forms, with a spinel structure. Above 1050 °C the mineral Mullite (Al6Si2O13) forms. This mineral was first found in nature on the Scottish island of Mull6 where small quantities of muddy rock were engulfed in lava and so heated above 1000 °C – nature’s own failed attempt to make porcelain. Within baking porcelain, Mullite initially forms in the shape of plates (platelet Mullite) but above 1400 °C the minerals start forming in the shape of needles. Plates can slide against each other, but needles cross and interlock with other, so this final change to the shape gives porcelain its great strength.

These are tremendous temperatures – it’s rare for rocks to experience such temperatures (except for within the deep earth) and Mullite is unusual in thriving under such conditions. Hessian crucibles were containers prized by alchemists and early chemists across Europe for their ability to survive whatever flames and chemicals were inflicted on them. Made to a secret recipe, only recently was it discovered that they are rich in Mullite.

Alchemists were in the business of finding miraculous transformations. The person credited with first discovering the secret of porcelain in Europe, Johann Friedrich Böttger, the “porcelain prisoner” was an alchemist imprisoned and instructed to turn lead into gold. After 14 years, having discovered a different form of profitable transmutation and brought the Meissen porcelain factory into being, he was finally released.

What to our ancestors seemed miraculous we take for granted. Let’s take a sip and pause to thank those people – Chinese and European – whose hard work lets us transmute mud into practical elegance.