“If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” Carl Sagan.

I have a handsome piece of rock in my hand. How did it come to be, how was it made? A perfectly acceptable geological answer is that it formed as molten rock cooled slowly underground. But that’s not the whole story, it doesn’t say what melted, and where that come from and…

So, taking my cue from Carl Sagan, here’s the full story.

Inventing the Universe

The Universe was created in a ‘Big Bang’ (if you want to know what happened before that, you are reading the wrong blog). At first, only three elements existed, Hydrogen, Helium and Lithium, basically just simple arrangements of sub-atomic particles. As the universe calmed down a bit, clumps of gas grew and grew, increasing the density in their centre. Eventually the pressure squashed atomic nuclei so much that they fused together, producing energy. The first stars were born.

These nuclear-powered furnaces produced light and heat, but also performed alchemy, turning simple nuclei into larger ones, thereby creating new elements. Getting from a nucleus with a few protons and neutrons to ones with over 100 (as seen in heavier elements) is not easy. Several generations of stars were required, gradually building larger and larger nuclei. The heaviest elements only form in the extraordinary conditions that occur in the least few seconds of a supernova, where large gobbets of protons and neutrons are forced together.

The modern universe has seen several generations of stars come and go, during its 13.75 billion years of life. As wells as stars, galaxies and the like, it contains chemically complex clouds of gas and dust, the mixed remnants of exploded stars. Hydrogen is still dominant but plenty of other elements exist. Over 150 organic molecules have been recognised, including vast quantities of ethyl alcohol, otherwise know as booze. Our own solar system formed from such a gin-soaked* cloud over 4 and a half billion years ago. The atoms that the rock in my hand, and you, and everything else you can see are made of was in there. Arranged rather differently, but there nonetheless.

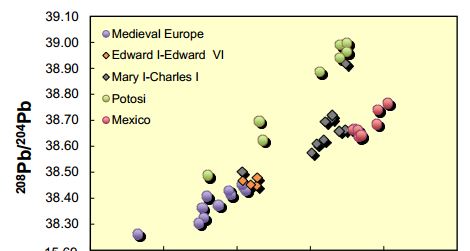

The cloud contained elements in different forms, such as tiny grains of diamond, formed in supernova shockwaves. They are found today in meteorites, precious little gems older than our solar system. Other grains were present (notably ‘CAIs’ or Calcium-Aluminium inclusions) but many elements were in the form of gas or ice. These ‘volatile elements’ are distinguished from refractory elements found in grains. Unsurprisingly compounds we know of as gas or liquid were in the volatile component, but it also included elements we think of as solid, such as potassium and lead.

Inventing the solar system

Some eddy, some chance event, created a part of the cloud, denser than the rest, that ended up as our sun. As its nuclear furnace ignited, strong solar winds started pushing through the rest of the cloud, blowing out the gas and ice, leaving only dust and larger solid fragments. The gas, ice and volatile elements were pushed out beyond a ‘snow line’ about 4 earth orbits from the sun, where some ended up as part of Jupiter and Saturn, the ‘gas giants’.

The earth’s composition today is measurably different from chondrites, a class of meteorites that records the composition of the original cloud. Indeed the whole of the inner solar system is depleted in the volatile elements that were blown away in the gas and ice.

Over 100s of millions of years the inner solar system formed into the four planets we see today. This was a violent process. Chunks of rock called planetesimals formed and then smashed together. Mercury and the earth-moon system clearly show the marks of major collisions early in their history. This violence is convenient for us, as it provides evidence for what is going on deep within the earth.

Inventing the earth

Many meteorites are fragments of planetesimals that have been smashed into pieces. These fall into two main camps, stony meteorites and iron meteorites. To a first approximation, stony meteorites match rocks we find on the earth’s surface today. Iron meteorites are clearly exotic to us surface dwellers, but they would feel right at home in the centre of our earth.

As planets form they separate out into two chemically distinct portions- a silicate part and an iron rich part. Iron is the sixth most abundant element in the universe – stars make lots of it – and it is refactory. It’s the most common element in the earth. There is so much that some of it doesn’t bond with other elements but sinks down into the core. It takes some friends with it – siderophile (iron-loving) elements such as nickel, gold, platinum and iridium.

The remainder of the planet, the equivalent of the stony meteorites, is known to geochemists as the ‘bulk silicate earth’ and now makes up the earth’s mantle and crust. It is rich in lithophile or ‘rock-loving’ elements which like to bond with oxygen and hang out together. We can’t see the earth’s core directly, just infer its properties remotely, so iron meteorites give us a glimpse of a place we can never visit.

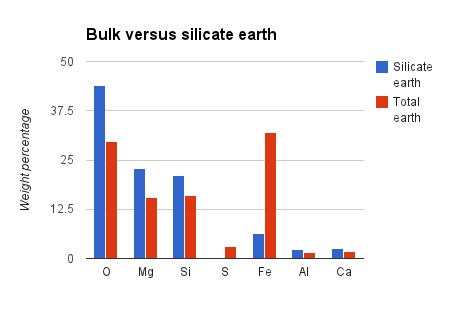

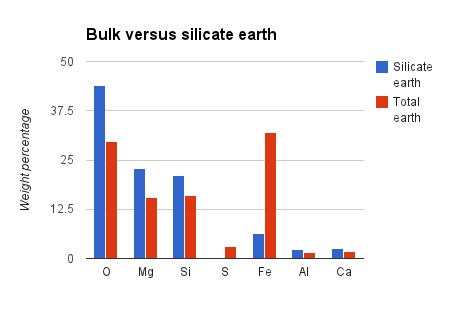

Geochemists are still settling the details, but the broad pattern is clear. Take the volatile elements away from the original cloud and you get the bulk composition of the earth. Extract out excess iron and friends and you are left with the bulk silicate earth. Here’s a rough graph of the composition of bulk versus silicate earth.

Taking out large amounts of iron into the core, leaves the other elements in increased proportion. Note how only six elements (oxygen, magnesium, silicon, iron, aluminium and calcium) make up nearly 99 percent of the bulk silicate earth. A silicate is a compound that contains SiO4,, so looking at the numbers, its no surprise that these are common. What’s that? You’re wondering if iron and magnesium oxides are common? Oh yes indeed. The earth’s mantle (the vast majority of the silicate earth) is made of peridotite** which is made of olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4) and orthopyroxene ((Fe,Mg)SiO3) plus other minor minerals that contain calcium and aluminium.

Taking out large amounts of iron into the core, leaves the other elements in increased proportion. Note how only six elements (oxygen, magnesium, silicon, iron, aluminium and calcium) make up nearly 99 percent of the bulk silicate earth. A silicate is a compound that contains SiO4,, so looking at the numbers, its no surprise that these are common. What’s that? You’re wondering if iron and magnesium oxides are common? Oh yes indeed. The earth’s mantle (the vast majority of the silicate earth) is made of peridotite** which is made of olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4) and orthopyroxene ((Fe,Mg)SiO3) plus other minor minerals that contain calcium and aluminium.

Melting the mantle

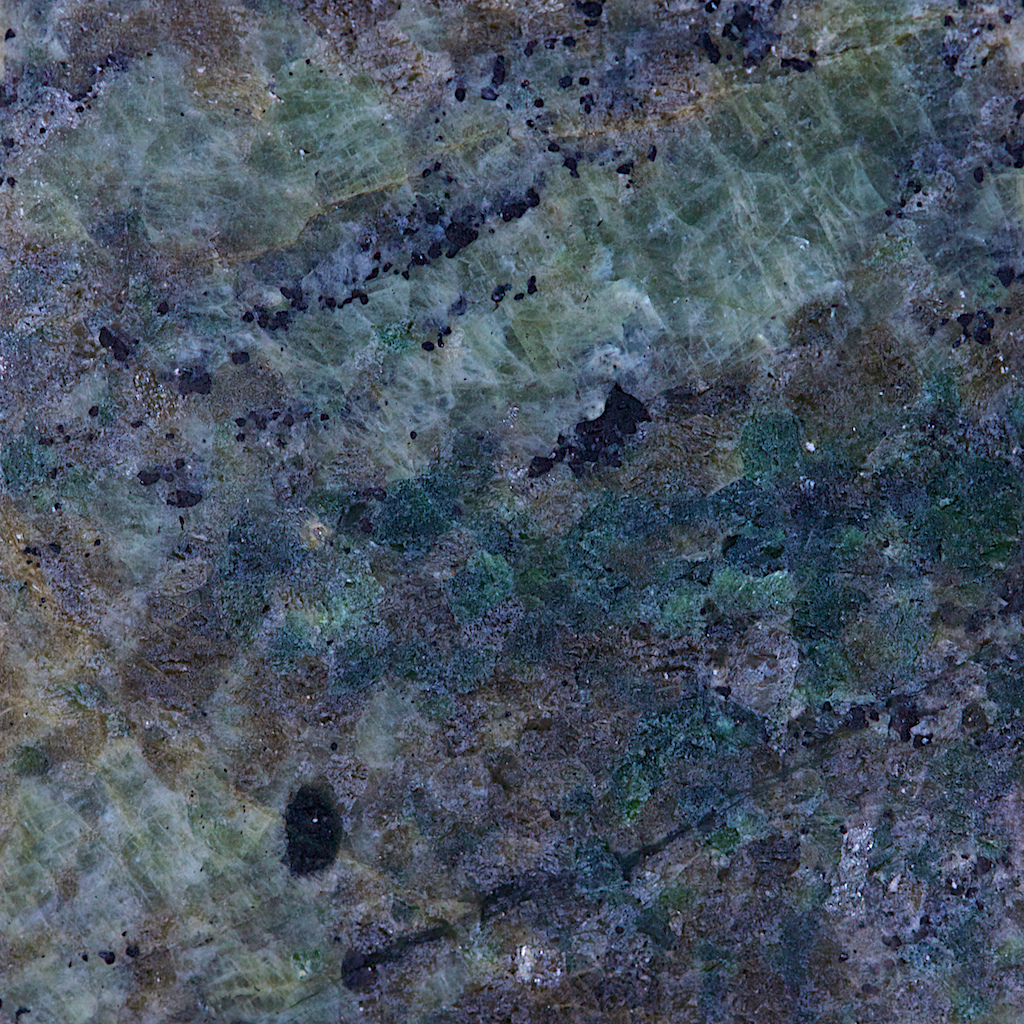

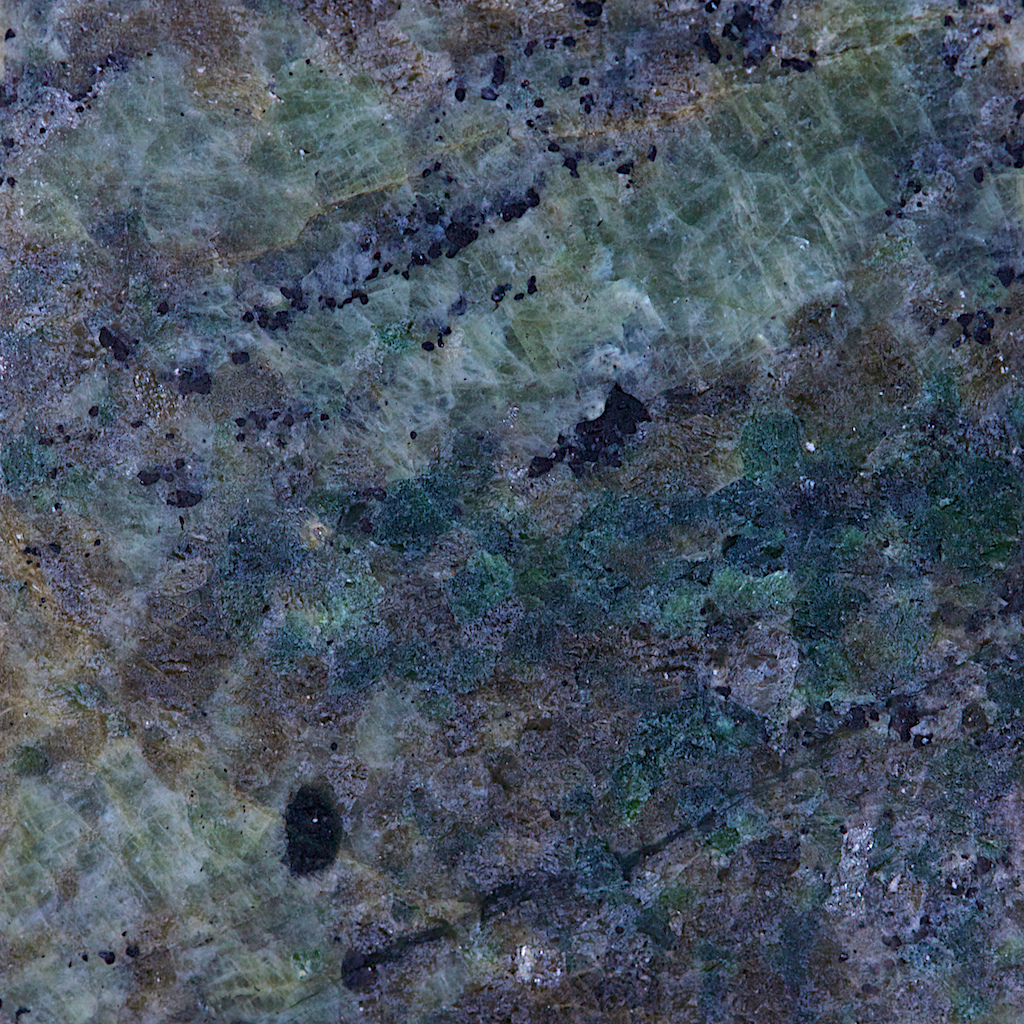

Picture your favourite rock. Unless you are odd, its not peridotite. So where do the pretty rocks come from? They are found on the earth’s continental crust, which is volumetrically unimportant, but much more varied than the mantle. Here a whole range of chemical processes are active: weathering, biological activity, metamorphism. I’ll stick with just one as it made the rock in my hand*** and it is how crust forms from the mantle: melting.

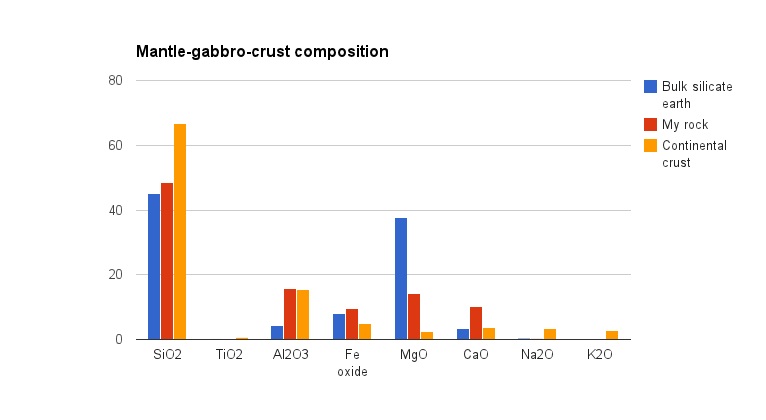

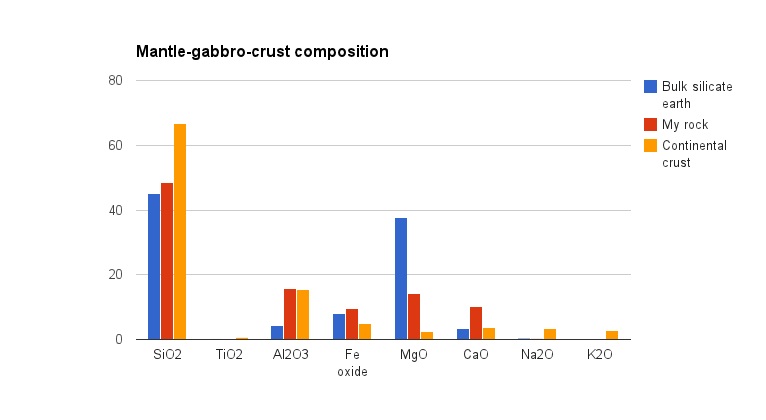

The mantle melts for a variety of reasons (great overview here) and it is yet another process of chemical change. The proportions of the major elements are different between peridotite and the molten rock, plus the melt is richer in the minor elements, which aren’t particularly at home within peridotite. Melting and re-melting has allowed the continental crust to be enriched in the interesting 1% of elements and produce rocks very different from peridotite.

Note how oxides such as sodium and potassium which are negligible in the bulk earth are much more common in the continental crust. The same applies to most other rock-forming elements.

My rock, the red bars above, is a gabbro from Ireland which was melted directly from the mantle. It contains pyroxene, which handles the iron and magnesium, plus calcic plagioclase, which mixes the aluminium and calcium with silicate and a sniff of sodium. The gabbro now forms part of the continental crust and as it is eroded away it will end up enriching sediments and going through yet another cycle of chemical change.

Water, water everywhere

I’ll try your patience with a final wet coda. The magma from which my rock crystallised was pretty dry, but it intruded into wet rocks (metamorphosing sediments). After the magma crystallised, it cooled and water from the surrounding rocks crept in and created new wet minerals. Where did this water come from?

Water**** was driven off from the inner solar system by the early solar wind. It’s extremely volatile, so why is it on the modern earth? Over the whole earth there isn’t much (only about 500 parts per million) but its concentrated near the surface. One popular theory is that it came via meteorites – wet ones from beyond the snow line.

This is an extraordinary idea, especially when you consider how important water is. Despite being such as small proportion of the overall earth, water drives processes that influence the entire planet. Subduction, the process where oceanic crust (sometimes) sinks down to the base of mantle, is facilitated by water. Water is involved in the formation of eclogite which makes oceanic plates more dense and allows them to sink. It also drives mantle melting that forms continental crust that allows us to keep our feet dry. Venus lacks plate tectonics and is drier than the earth – is this explained by how many wet meteorites fell on one planet and not the other?

If a defining feature of earth is only here by chance, it certainly puts the search for ‘earth-like’ planets into context. When we find planets of earth size within the ‘goldilocks’ zone (of orbits that allow liquid water) slight differences in their history may mean they are still far from ‘earth-like’ in their ability to support life.

Whatever the events necessary to create life on earth, one of the things it does is make apple pies. My work here is done.

——————————————————————————————————————-

*being pure alcohol it’s nearer vodka than gin (juniper didn’t exist), which is a shame. No tonic in space either.

**olive and pyroxene are stable only near the top of the mantle. At greater depth and pressure other more exotic minerals (with similar chemistry) are stable. But that is another story

*** it’s made typing quite difficult, I should probably put it down now

**** I say water when I should perhaps use water/hydroxyl/hydrogen, but you’ll forgive the simplification, I’m sure

Picture of peridotite from the incomparable hypocentre on Flickr under creative commons.

This post draws a lot on the book Destiny or Chance revisited by Stuart Ross Taylor.