My cup of tea is sitting nearby1, the rocket-fuel for the mind is sitting in a piece of man-made metamorphic rock and lying on the saucer is a humble object that bears mute witness to ancient, earth-changing events.

Tea in England is typically taken with milk and sometimes with sugar – lots if it’s “builders’ tea” – and a small spoon is required to add and blend the ingredients. These spoons can be made of silver or even gold. I’m not a Duke or a Prince, so mine are made of stainless steel.

Steel is an impure form of iron and has been made for thousands of years. The use of Archaeological periods (Iron Age succeeding Bronze Age) works because smelting iron tools is harder to do, but gives a better product than bronze. Strong and sharp iron tools are excellent for slicing through both fields and people. Successful Iron Age societies such as the Roman Empire were based on both swords and ploughshares, working together.

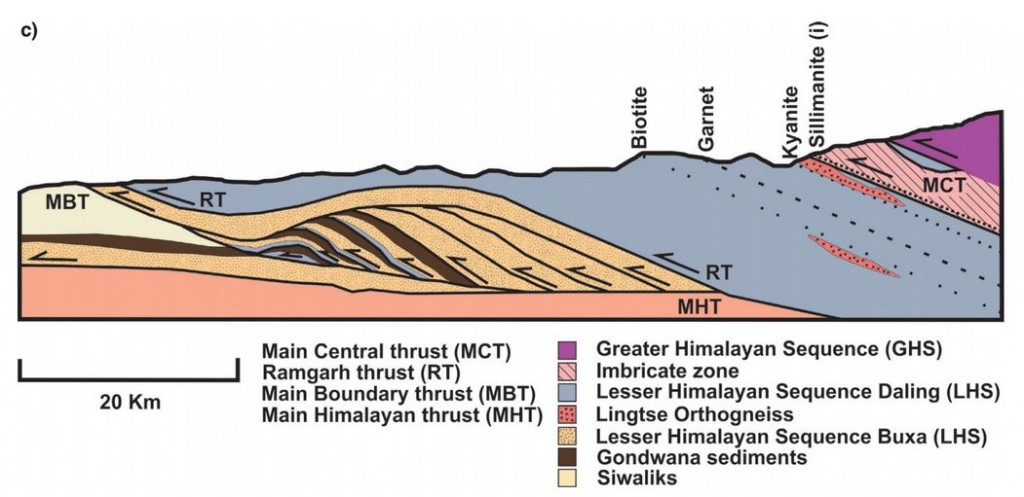

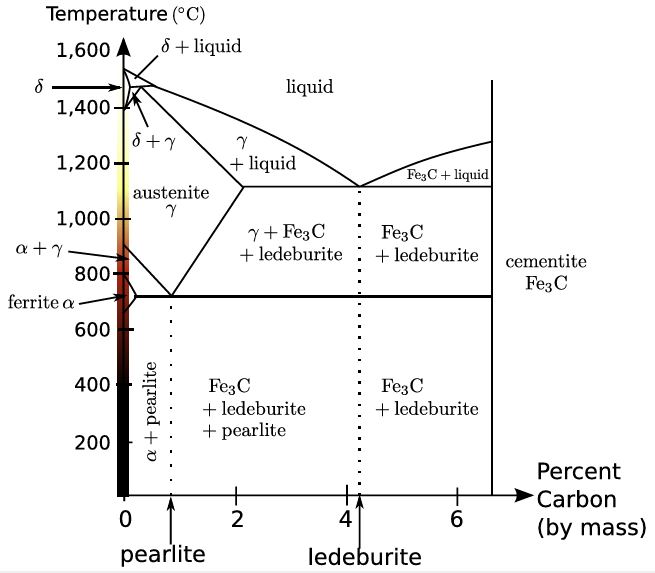

Iron-carbon phase diagram. From Wikipedia

Much as with ceramics, small differences in the processes used can make a huge difference in quality of the end product. Molten iron easily mixes with carbon, which was originally introduced from the burning charcoal used in the furnaces. Mixing different amounts of carbon within iron results in different phases (with different atomic structures) – as the phase diagram above shows. This sort of diagram will be familiar to anyone who’s studied igneous petrology. It can be used to predict which minerals are produced in which order when a molten substance is cooled. Producing a molten mix of carbon and iron of the correct composition and cooling it at a rapid rate results in a fine-grained mix of different materials that is strong yet not brittle.

Our ancestors worked all the best forms of steel by trial and error over generations and in many different places. Getting hold of iron ore was never a major issue as iron is one of the most common elements on earth and beyond. It’s atomic nucleus is one of the most stable and a common product of stellar furnaces. Indeed the earth and other rocky planets are so rich in iron that as well as forming part of many silicate minerals in the mantle and crust, left over iron trickled down into the centre of the earth where it forms a dense magnetic core.

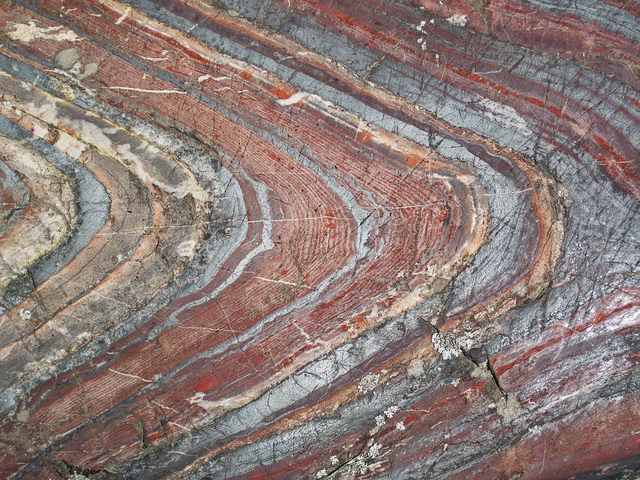

Banded Iron Formation. Source: James St. John on Flickr

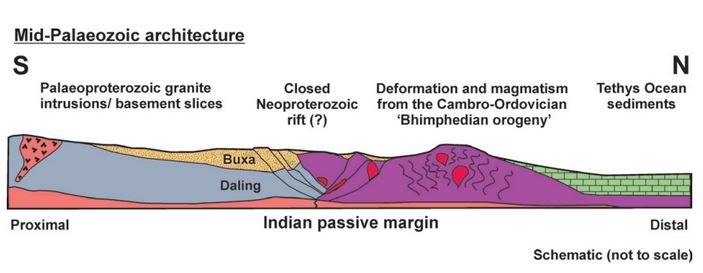

Much modern iron comes from deposits that have their roots in a remarkable transformation of the earth- the “great oxidation event”. The early earth was a very different place with no oxygen roaming ‘free’ in the air – this reactive element was everywhere bound up with other elements. Iron at the surface was mostly in the reduced ferrous form of iron that easily forms compounds soluble in water. The first forms of life that lived via photosynthesis were tremendously disruptive. The Oxygen they produced never reached the atmosphere but quickly reacted with the surrounding seawater. Often it reacted with iron, changing it from ferrous into ferric iron that forms compounds that are not soluble in water. These same compounds are familiar to us as red rust.

Slowly, photosynthesising organisms turned dissolved iron into layers of iron minerals on the sea-bed. Over several billions of years, grain by grain, these bacteria produced huge volumes of iron-rich sediment. These banded iron formations are found in ancient rocks around the world and form the great iron-ore mines of Western Australia that have helped build modern industrial China.

Eventually the critters won. The earth ran out of ferric iron and the oxygen stopped reacting in the sea and started bubbling into the atmosphere, building a world, our world, that would in time support oxygen breathing animals who sip tea.

The iron in my spoon, was once transformed by the caress of ancient slime, but now it is nearly pure metal, strong and shiny. Surrounded by Oxygen, it is under threat – the Oxygen could bind with it again, undoing the smelting process and turning it back into rust. To counter this – to make it stainless steel – just over 10% of Chromium has been blended in. Chromium is not resistant to Oxygen’s charms either, but the resulting oxide does not let Oxygen pass through. This process of passivation means my spoon has a thin protective film over it, keeping it shiny even in the hostile toxic environment of my tea cup.

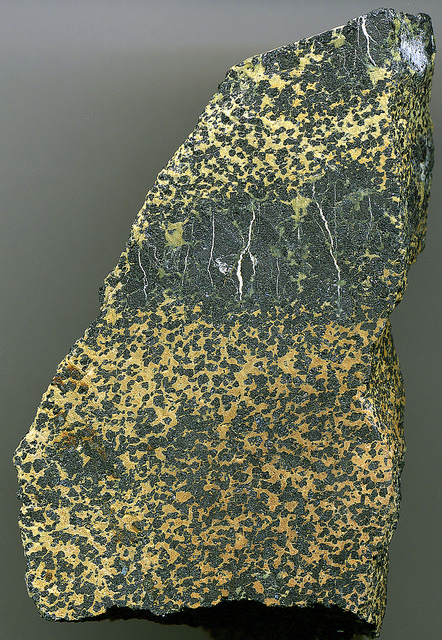

Chromite in Serpentinite. Source: James St. John on Flickr

The Chromium in my spoon probably came from South Africa. It is a relatively uncommon element and places where it is concentrated enough to mine are not easy to find. The best place is in a large igneous intrusion formed from the melting of the earth’s mantle. The magma itself isn’t very rich in Chromium, but the biggest intrusions cool very slowly, which allows layers of different minerals to form. We’re still not exactly sure what the exact processes are, whether the minerals sink to the bottom of a pool of molten rock or form later at the slushy mushy semi-solid stage (probably it’s a bit of both). As the owner of a spoon we don’t need to know, just to be grateful that some of the layers are so rich in a mineral called Chromite they form a rock called chromitite.

There is a massive frozen magma chamber where this has happened in South Africa. Called the Bushveld intrusion it is rich in Chromite, and also most of the earth’s known reserves of Platinum group elements. It was formed from a million km3 of magma that was intruded into the crust 2 billion years ago. To put that in context, that would fill the Baltic Sea fives times over. Four Bushveld’s worth of magma would fill the Mediterranean Sea with some left to slop over the side, making a hell of a mess. The Bushveld is an amazing thing, if a little overshadowed by the gold and diamond mines and the massive eroded meteorite crater that sit nearby.

Science and history isn’t just something that sits out there somewhere, in museums, or distant galaxies. It can be found within the most ordinary of objects. These stories aren’t just stories. We can’t identify which ones, but some of the iron atoms in my teaspoon were affected by the great oxidation event. The same atoms really were there billions of years ago. My choice of tea as a drink is not a simple act of will; I’m guided to it by global events hundreds of years ago. Look deeply into anything around you and there are amazing stories to tell.