In Accretionary Wedge #41 – “Most Memorable/Significant Geologic Event That You’ve Directly Experienced” Ron Schott asked us to relate the story of the most memorable or significant geological event that you’ve directly experienced.

Living far from a plate boundary, I have a problem. There are no volcanoes in the UK. We have feeble earthquakes every now and then, but I always seem to be away or asleep when they happen (that’s right, these are earthquakes you can sleep through). I’ve witnessed rock-falls and erosion, which are important, but really I’ve not experienced any significant geological events at all. Which, come to think of it, makes me rather like a lot of the geological record.

Consider a nunatak in Antarctica. This is a lump of rock sticking out of the ice-cap. It is surrounded by ice for miles around and nothing happens. Cosmogenic nucleide studies show that the rocks surfaces are millions of years old. So little has happened that blobs of glass that fell from the sky the best of a million years ago (tektites), can be easily found on them.

On a bigger scale, Australia has had a quiet time of it since the dinosaurs. Many land surfaces on that continent are dated to be 10s of millions of years old. Weathering and soil formation has happened, but little else of geological significance.

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, but I can’t talk about nothing and Geology without mentioning unconformities. James Hutton’s realisation that these surfaces between rock packages can represent gigantic periods of time led us to the recognition of Deep Time, one of the most profound insights we have.

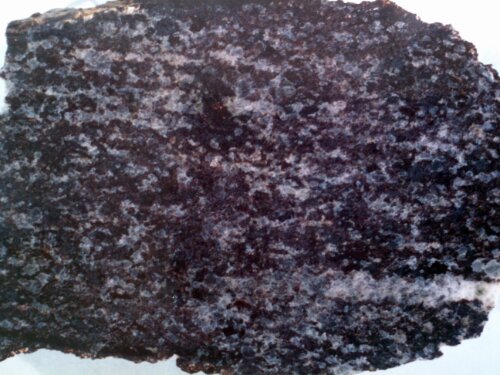

Unconformities are the most dramatic reminder of the amount of geological time for which we have no record, but a simple outcrop of sediments can do the same. Most sediments don’t represent a continuous record of sedimentation. Turbidites tend to record only occasional dramatic episodes of sedimentation. The steady drip-drip (or is that drop-drop?) of pelagic sedimentation is only intermittently preserved in such rocks. Sometimes we admire only the products of dramatic events and forget the huge periods of time in between. Even a calm-looking sandstone might in fact be mostly made up of storm deposits. A package of conformable sediments can contain huge gaps, but only subtle hints such as beds with intense bioturbation give a sense that for great periods of time, nothing happened, for all we can tell.

We should think about nothing more often. Thinking of Geology as a series of dramatic events is all very well, but its the enormous chunks of nothing that are truly remarkable. The human brain isn’t equipped to understand quite how insignificant we are in terms of space or time. Perhaps we should think about this more often, while staring at nothing.