This is my contribution to the ‘most important teacher’ Accretionary Wedge.

I’ve had the privilege of learning from many excellent teachers. Choosing one single person to talk about is somewhat arbitrary. I’ve chosen someone who, of my teachers, is the most important figure in the wider world.

Professor John Frederick Dewey is an major figure in geology. He’s a Fellow of the Royal Society, a member of the US National Academy of Science and winner of numerous awards and accolades. He’s held professorships at prestigious universities both sides of the Atlantic and has taught over 40 PhD students and countless undergraduates. Most interestingly, he was there at the beginning. He’s part of the generation for whom plate tectonics was a fabulous novelty, a bolt from the blue that transformed the study of the earth in so many ways.

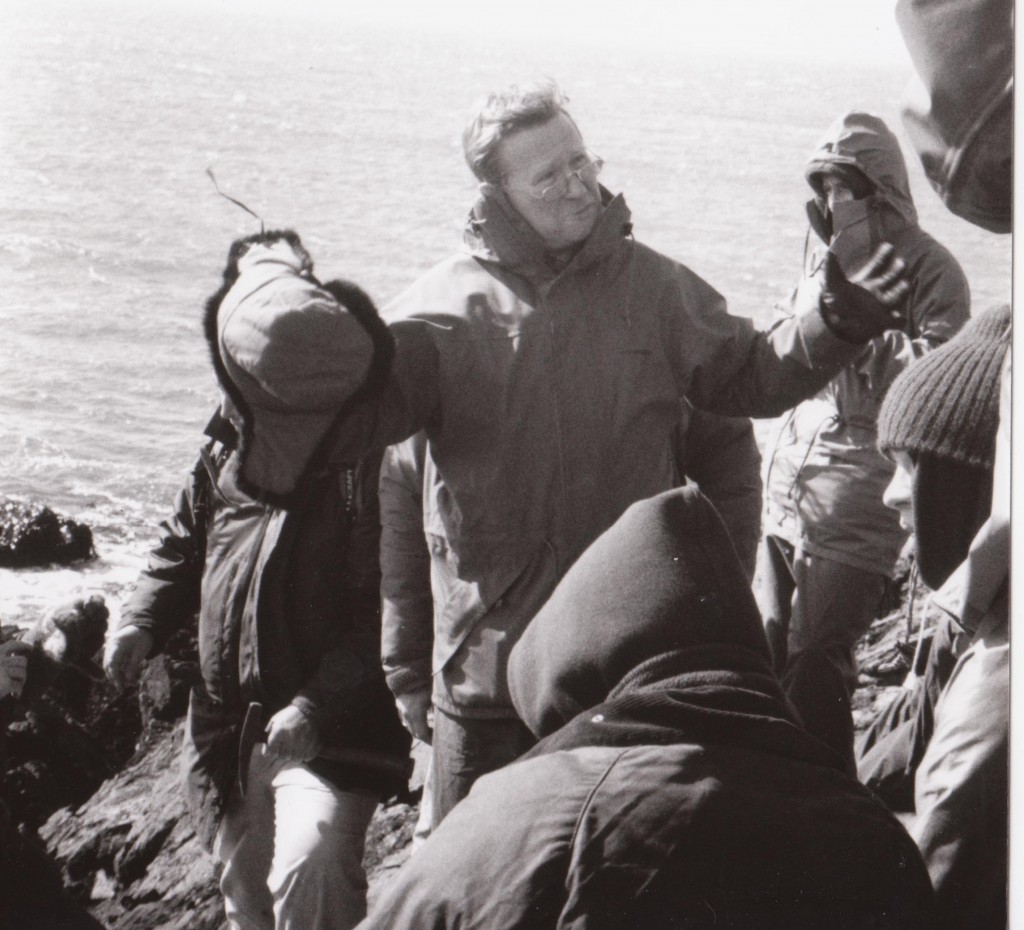

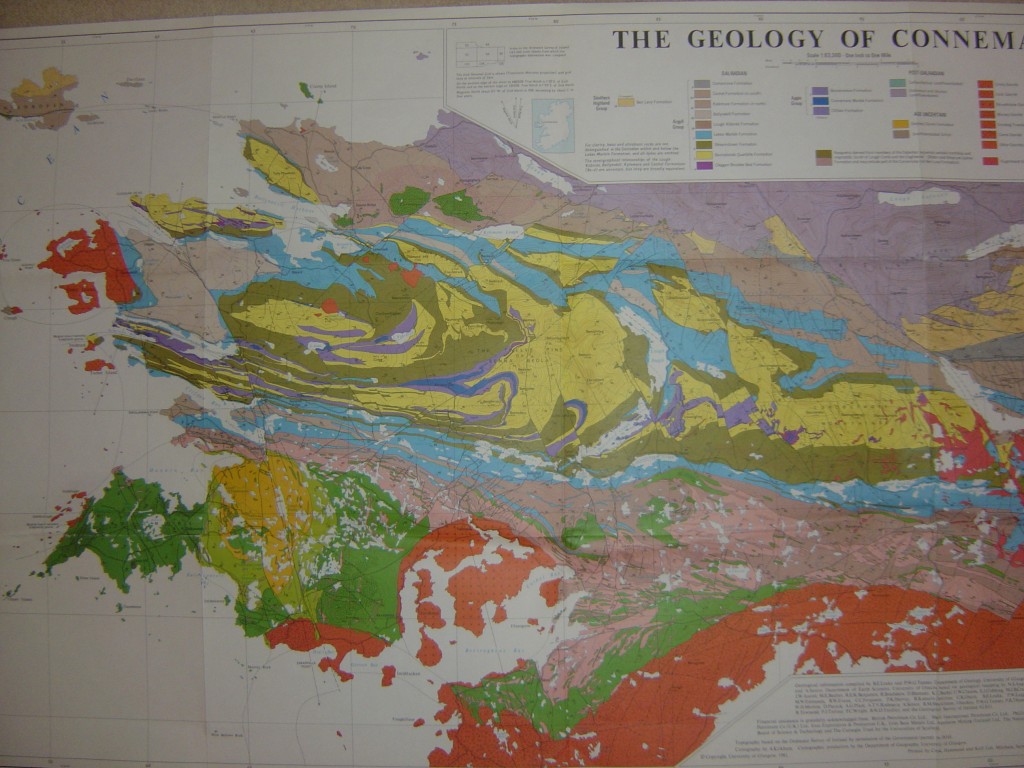

John made his career by being one of the first geologists to apply plate tectonic theory to specific mountain belts. This involves the impressive trick of linking field-based studies to high-level plate tectonic concepts (e.g. “closure of ancient ocean, then collision of oceanic island arc then closure of ancient ocean”). Throughout his career he’s covered pretty much every orogeny on the planet and many types of concept (orogenic collapse, transpression/transtension to name but two). To give a flavour of his depth of geographical coverage, the hat in the picture above was a Chinese Army one from a trip across Tibet and I’ve see him have a good natured debate over which is the best fish-restaurant in South America. He is currently based in California but his home-base as regards Geology is the West of Ireland, where he did his PhD research.

As you can see from the above, John is a bit of a showman. I know him best from 5 years of Irish undergraduate field trips. Sitting in a wrecked bog-car to amuse the students is entirely in character, as is eating raw mussels, freshly ripped from the outcrop, to show how clean the Atlantic sea-water is. Every year in Ireland, he would allow an hour or so to make everyone play cricket, often on a road. Western Irish roads are often an arena of oddness (I was overtaken by a hearse once) but 40 young people in rain gear and one Fellow of the Royal Society knocking a ball around is still a rather unusual sight, even there.

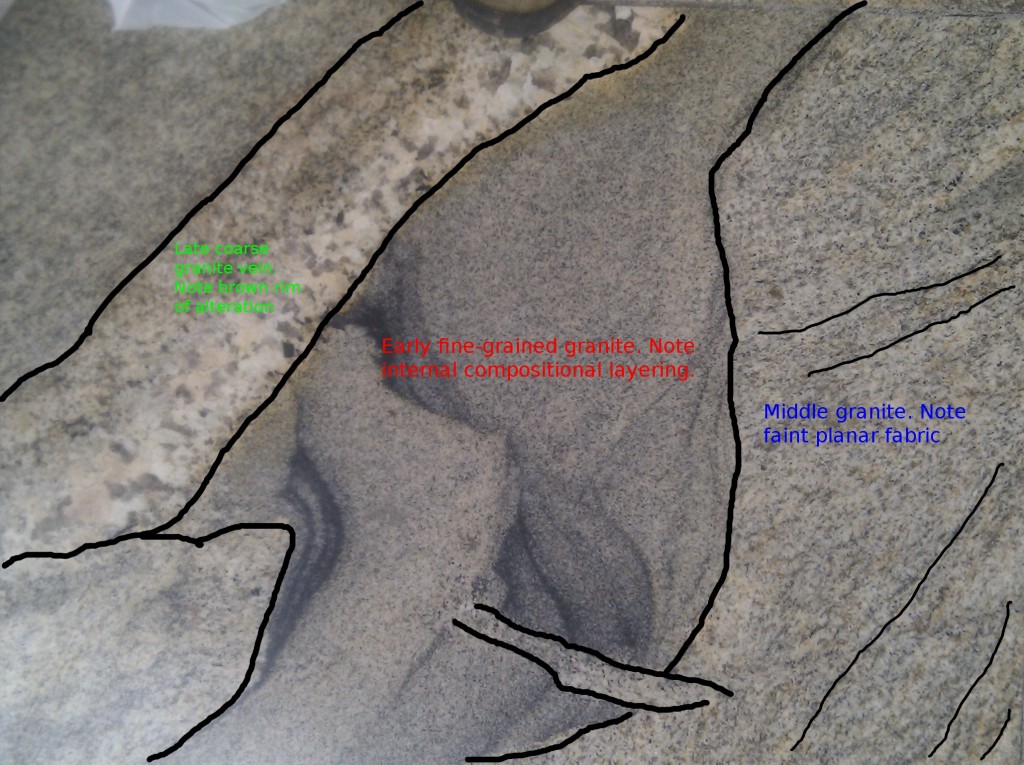

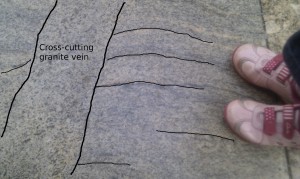

What did I learn from him? Firstly, a love of tectonics and the grand intellectual game of understanding how mountains form. It’s exhilarating to hear him talk on this subject. Take my own research on Irish rocks (which he co-supervised). For John this is a tiny brick in a grand edifice, helping him correlate the geology of Ireland with that of Scotland to understand the Grampian orogeny. This is then a part of the grander picture of the closing of the Iapetus ocean, which formed the Caledonidian (British Isles, Greenland), Scandian (Norway) and Appalachian (US and Canada) orogenies. The short duration of the Grampian orogeny allows comparisons with New Guinea and contrasts with the Alps and Himalayas. To stand on a single Irish outcrop and link it into an intellectual scheme that spans and seeks to explain the entire world, this is real science.

Another, broader thing I learn from him is the importance of mastering the detail, but also lifting up your head to the broader things. To succeed in many professions you need to master the detail, to learn a craft and have specific skills. But to really get on you need to link this to a bigger picture. Detailed careful work is important, but maybe its worth spending less time on dotting every i and more time on telling a great story, making a splash and creating research that is seen to be interesting and important.