The further you go from home, the more exotic things become, whether for holidays, or for an imaginary journey straight down. There are wonders under your feet, much closer than you think.

We’ll start from my house, in an unremarkable suburb of Reading, an almost-city in the Thames Valley, west of London, England.

Put a spade into the ground in my back garden and it sinks in gratefully. This is well-cultivated soil, dug for Britain during the war. The stones within it are mostly flint, occasionally fossils and mostly rounded. Immediately below the soil is a gravel terrace laid down by the River Thames.

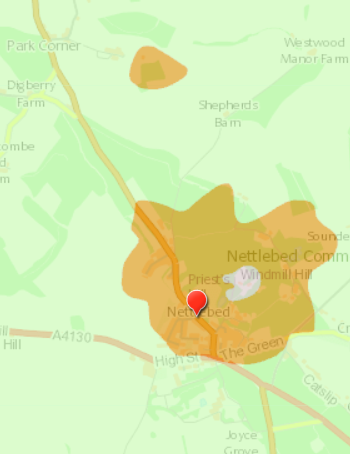

This gravel is extremely useful in construction and widely extracted. A map of Reading shows many bodies of water, dug for the gravel. The entire area is covered in these terraces, of various ages. The further up and away from the modern river you go, the older the terraces – they trace how the river has slowly cut its way into the landscape.

My house is not so close to the river, so the gravels are about 250 – 300,000 years old, a time a few ice ages past, when humans had learned to make fire and stone tools. A gravel pit behind my house unearthed some of these tools, now in Reading museum.

We’ve travelled just 6 metres. Below the gravels we get the first ‘solid’ geology – the London Clay and Lambeth Group, layers of sand, silt and mud around 50-60 million years old. Dramatic things were happening at this time – huge volcanoes formed in the west of Scotland, India first collided with Asia to form the mighty Himalayan mountains. In SE England alas, not much was going on, just a bunch of mud and sand being draped over the surface.

What’s most interesting about these rocks is what people did with them. Particular layers are good for making bricks and this has shaped the local area. Reading town centre is full of fine Victorian brick-buildings. The local clay gives red bricks, but mixing in quantities of chalk gave a grey coloured brick. Bricks were made across the Thames Valley, wherever suitable clay was found.

Unlike older, more deeply buried sediments, these rocks are still soft and poorly bound together, something that led to the first ever serious railway accident. The Great Western Railway was originally planned to run through the village of Sonning, close to the Thames. However an uncooperative land-owner forced the route to go through a small hill. Any plans to tunnel through were dashed by the low strength of the sediments. Instead a cutting was made – a 17m deep gash through the hill – with the railway running at the bottom of it. On the 24th December 1841, a landslip covered the rails with ‘soil’. A train ran into the slip, causing the deaths of 9 people. These were early days for both railways and engineering geology – the cutting was later widened, making the slopes less steep.

Only 24m below my house, we reach the Chalk. This is a rock-type that is both an icon of Southern England (“white cliffs of Dover”) and deeply weird.

While most sedimentary rocks are made of sand or mud, chalk is almost entirely made up of the remains of living creatures. Sea-levels at the time (95-65 million years ago) were extremely high, meaning much of Britain was underwater. Since little or no sand or mud was being washed into the sea, the only things settling on the sea-bed were the remains of tiny planktonic organisms. These grew tiny beautifully shaped flakes of calcium carbonate that found their way to the sea-bed, building up layer after layer. Other creatures, like sea urchins living in this chalky mud had parts made of silica. These formed into nodules black flint, so prized by our distant ancestors. Rare stones are found in the chalk, thought to have polished in the insides of giant sea monsters, marine reptiles that swam these seas.

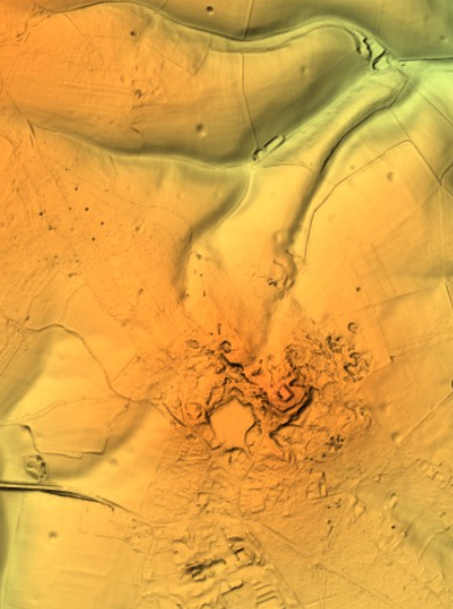

Chalk landscapes form the bones of southern England. Slightly harder, they form ridges such as the Chilterns and South Downs. These are strange landscapes, dotted by prehistoric structures and mysterious figures formed by cutting through the thin soils to reveal the pure white chalk beneath.

These chalk hills have sinuous valleys and whale-backed hills. The valleys are dry – chalk is a rock that swallows rivers and is in turn dissolved by water. Near me, above the chalk, a swallow hole recently appeared in a school car park, a reminder of the chasms beneath our feet.

There are creatures beneath my feet. The chalk aquifers are home to creatures called stygobites, ghostly crustacean that eke out a living in wet cracks. Some are thought to have been living in England for up to 19 million years, making them our longest continuous inhabitant

The remains of more ancient life lies deeper still. As we shall see, next time.