Castle Geology

Cross-posted at Highly Allochthonous

Being a giant geo-nerd, I tend to pepper my travels with a lot of geologically or hydrologically interesting places. A recent trip brought me to the UK and included a meetup with my Highly Allochthonous coblogger in Edinburgh. Being an American tourist, I also felt compelled to visit at least one castle during my time in the UK, so I dragged Chris to Edinburgh Castle…where we naturally we ended up talking about the geology.

Edinburgh Castle from Princes Street. The low area with gardens in the foreground used to be a loch/lake. (Photo by A. Jefferson)

First off, Edinburgh Castle sits atop the core of a Carboniferous (340 million year old) volcano, now called Castle Rock. The rock is impressively elevated above the surrounding glacially sculpted cityscape. The volcanic root formed a bit of a speed bump for Pleistocene glaciers moving from west to east. Castle Rock was more erosion resistant than surrounding sedimentary rocks, so it was left standing higher than the surroundings. But it also protected the sedimentary rocks in its lee – forming a giant crag and tail structure. The Royal Mile, which stretches from the Castle to Holyrood Palace rides on the tail of this structure – which gradually decreases in height and width away from the castle. In the Google Earth image below, I’ve maximized the vertical exaggeration and you can get some sense of it, though I can tell you that a more visceral understanding is achieved by walking up or down the Royal Mile.

Within the castle itself, the glacial legacy is on display in the building stones, which show a remarkable diversity of lithologies, both those found locally and those farther afield in Scotland. It is likely that castle builders would have made use of the rocks left on the landscape when the glaciers retreated, but the ice caps would have given them plenty of variety. In the middle of the photo below, I think we are looking at the Old Red Sandstone, which has an important place in the history of geology and of paleontology.

Stonework on St. Margaret's Chapel, the oldest extant building in Edinburgh Castle (photo by A. Jefferson)

The stone construction seemed to vary between buildings and even parts of buildings within the castle. The photo above is from St. Margaret’s Chapel, built in the 12th century, and you can clearly see how the big rocks are matrix-supported by a sand and gravel cement. This wall is actually even different from other walls on the same building, where stones are much more rectangular, probably cut, and there is much less matrix, as shown in the photo below. The informative castle guidebook suggests that the wall pictured above may have been originally part of another structure, onto which St. Margaret’s chapel was built adjointly. I should also point out that the walls in St. Margaret’s chapel are incredibly thick (1 m or more), so there’s a lot of stone work we’re not even seeing from the outside.

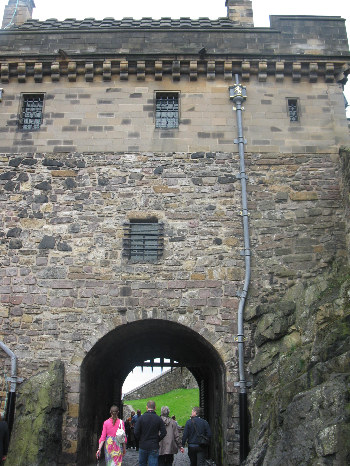

In other parts of the castle, and indeed in the surrounding city, it was fun to watch for places where old doorways or windows had been filled in or where additions had been added to stone buildings. These were usually pretty easily spotted by a change in the stone construction style. For example, in the photo on the left, you can see the main gated entrance to the castle (the Portcullis Gate), which was constructed in the late 16th century. On top of it is the Argyle Tower, one of the youngest buildings in the castle, constructed in 1887. To me it also looks like there might be an intermediate strata between the cut and tightly placed blocks immediately around the gate and the much more modern top part.

Wall adjacent to Lang Stairs. The plaque on the wall commemorates the successful recapture of the castle from the English in 1314. (photo by A. Jefferson)

Finally, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out one important hydrogeological influence on Edinburgh Castle and its history. As I mentioned, the castle is much higher than the surrounding topography (peak is 134 m above sea level) and made of dense volcanic rock. This has advantages from the defensive point of view, but a significant disadvantage from the “having enough water to stay alive” point of view. During peace times, castle residents presumably brought water up the hill from the loch or from wells in town. But during sieges, they were reliant on the Fore Well. This well, constructed in the 14th century, is an impressive 34 m deep (through solid rock! in the 14th century!), but only the bottom 3 m of the well are below the water table. The well could provide 11,000 liters – but that’s not a lot to supply a bunch of soldiers and their animals. During at least one siege, most of the deaths seem to be attributable to lack of adequate water, rather than the warfare itself.

So that’s what happens when you take an American geo/hydro nerd to Scotland…she looks at castles and thinks about rocks and water.