Everyone has heard of Eyjafjallajökull. Not everyone can pronounce it.

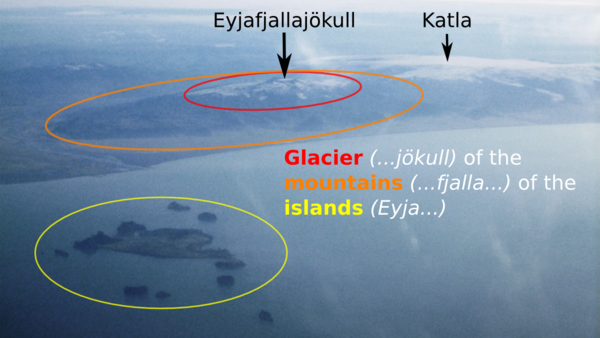

It is almost as infamous for its long name than for the travel disruption that it caused. But the name is much easier when you break it down into its component parts. These are Eyja (islands), fjalla (mountains) and jökull (glacier). The origin of each part is clear when you see the volcano from the air.

Eyjafjallajökull's name comes from the islands offshore, as seen in this view from above. Click for larger version.

The islands after which the volcano is named are the Vestmannaeyjar (or the Westman Islands). The largest is Heimay, where an eruption in 1973 partly buried a small town and the residents famously pumped seawater onto advancing lava flows in an attempt to divert their course. Out of view, below the bottom of the picture is the island of Surtsey, which was born out of the Atlantic during an eruption from 1963-1967.

In the upper right of the picture is the Myrdalsjökull glacier that covers Katla volcano. Since 2010, Katla has been more widely known as ‘that-volcano-next-door-that’s-even-bigger-than-the-unpronounceable-one’. Katla gets restless every summer, and is rumbling again now. You can see plots of earthquakes at the volcano over the last 48 hours (Icelandic Met Office) and over the last 2 years (Edinburgh University). It might erupt. Or it might not. The eruption might be bigger, but the disruption in Europe will probably be less than Eyjafjallajökull 2010, mainly because of changes to aviation rules.

Aeroplane-window geology

A tip for those flying from Iceland to the UK is to take a left-hand side window seat. If it is clear (if….), then you get spectacular views of lava flows, rivers, fault lines, glaciers and volcanoes all along the south coast of the country. Equally, chose a right-hand seat for flights from the UK. On summer evenings, these also provide the rare experience of seeing the sun rise in the (north) west.

This photo was taken in August 2011, on a flight from Keflavik to Glasgow. Erik Klemetti’s recent aeroplane-window pictures of Californian volcanoes on the Eruptions blog were the inspiration to post it now. I also wrote another aeroplane-geology-based post, On Transatlantic Flight, about a year ago. It explains how the Atlantic ocean is actually younger than the fuel burned to cross it.

Pingback: Recommended sources of information on Katla volcano | Volcan01010