Quite high, actually.

And I’m not just talking from a geologist’s perspective, where the planets whizz around the sun, the continents glide across the surface of the Earth, and volcanoes pop off continuously, like bubbles in a simmering stew. A fairly simple analysis of the frequency of Icelandic eruptions and the direction that the wind blows across the Atlantic shows that you could expect ash clouds over UK airports every few decades.

Just how active is Iceland?

It is clear that Iceland is a very volcanically active country. Since the turn of the century, we have seen eruptions from Hekla (2000), Grímsvötn (2004) and Eyjafjallajökull (2010). Notable eruptions of the last century include Gjálp/Grímsvötn (1996) which melted through the Vatnajökull icecap and caused a large flood (called a jökulhlaup), Eldfell/Heimæy (1973) where the townsfolk sprayed seawater on the lava flow in an attempt to divert it, and Surtsey (1963-67) when a new island was born out of the north Atlantic. But can you put a number on it?

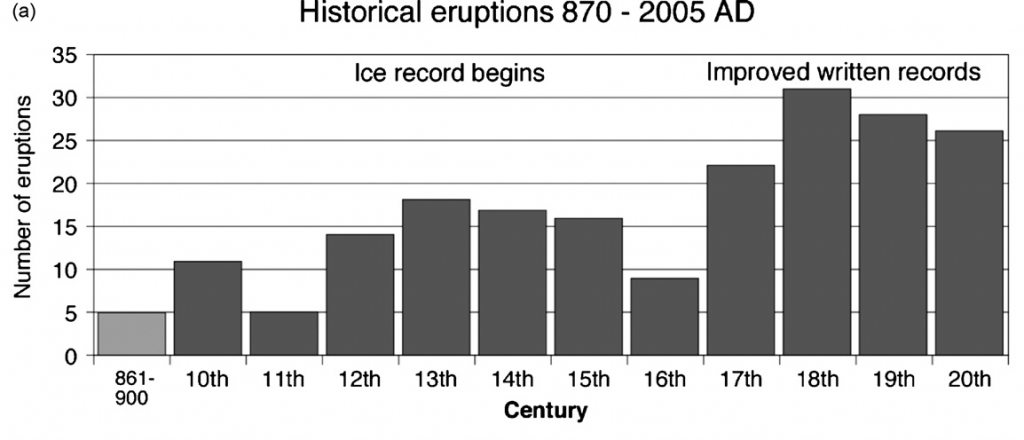

Fortunately, Icelanders are an extremely literate people, and their sagas and other writings are full of descriptions of “Earth fires”. These date right back to an eruption seen by the first settlers around 930 A.D. Studies of this literature, combined with field explorations to confirm that the deposits exist, find about 200 eruptions in the last 11 centuries. Of those, ~155 were explosive, and ash grains from at least 16 of them have been found outside of Iceland, in soils and lakes across northern Europe.

A similar eruption rate is found by studies looking at the past ~10,000 years. This period coincides with the time since the last ice age, and is referred to by geologists as the Holocene. Holocene eruptions can be counted by looking at lava flows and ash layers that have not been affected by glaciers, and we can work out when they formed using techniques such as carbon dating. So far ~2,400 eruptions have been identified, although ~500 of those didn’t produce much ash.

So both the historic and the Holocene records suggest that there are eruptions in Iceland about once every 5 years, and that about three-quarters of those produce ash.

Any way the wind blows

To understand the risk that these eruptions present to UK airports, we need to ask the question: “What proportion of the time will ash from these eruptions reach the UK?” A recently-published study by scientists at the UK Met Office provides our current best answer.

Using their NAME software (more on this in future posts) they simulated 17,000 eruptions of Hekla volcano, one every 3 hours from 1 Jan 2003 to 31 Dec 2008, using the actual weather data from the time. NAME is a computer model for atmospheric dispersal that predicts where ash grains are blown and dispersed by the wind, and is the one used by the London Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre to work out areas where aircraft might encounter ash. In each simulation the ash was erupted in a 12 km-high plume, at a rate equivalent to 2,400 tonnes per second, for 3 hours, then tracked over the following 4 days. An area was deemed ‘affected’ if the predicted concentration exceeded a certain threshold (equivalent to ~0.05 milligrams per cubic metre).

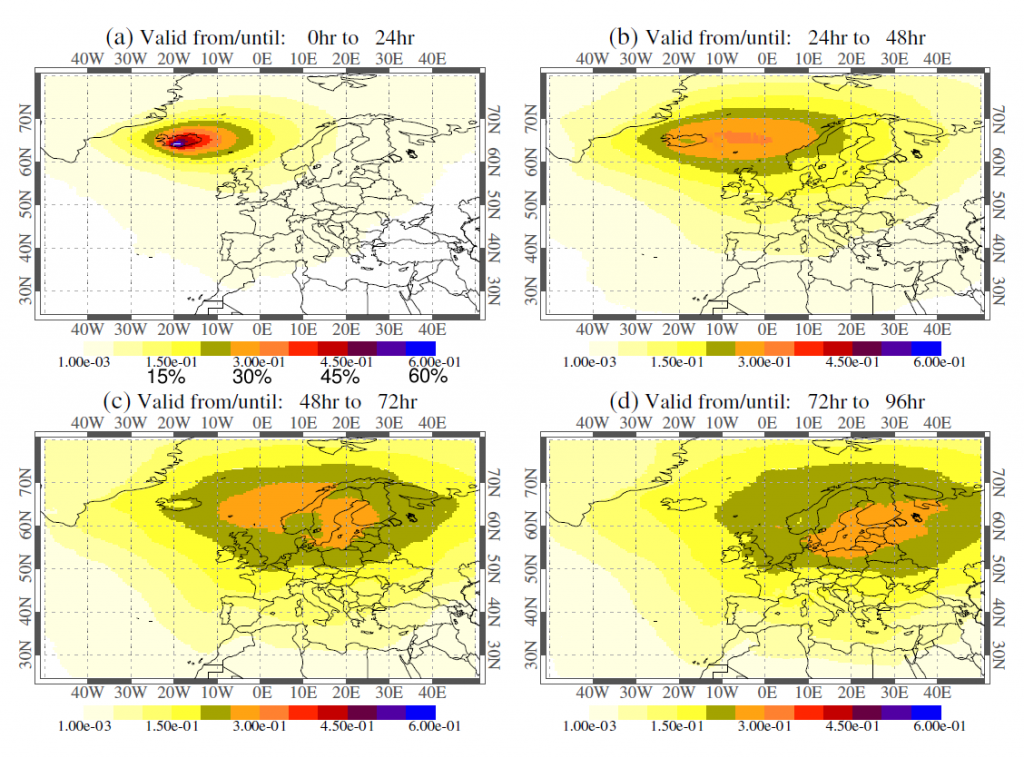

Probability of ash concentration exceeding threshold between surface and ~6000 m (20,000ft) - Leadbetter and Hort (2011)

The results of each eruption were added together to make maps of the probability of an area being affected by ash during different time periods following the eruption. Most of Europe above 50°N has a probability of at least 20% of being affected within 4 days. The results show the track of the “average” plume, reaching the North Atlantic (after up to ~24 hrs), then Scotland and Scandinavia (~48 hrs), followed by Western Europe and the Baltic sea (~72 hrs), and finally reaching Eastern Europe and Russia (~96 hrs).

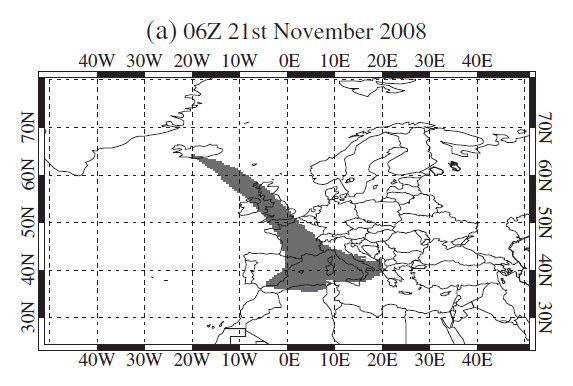

Of course the average tends to smooth things out. If doorways were built according to the average height, there would be a lot of banged heads! Individual scenarios, such as the one below, give a more realistic representation of the ash cloud shape. This example, where the winds blow the ash cloud directly towards the UK in less than 24 hours, has a 5-15% probability. Prior to Eyjafjallajökull, the last eruption to do this was Hekla 1947. You never hear about disruption to flights on that occasion because it was years before the commercial aviation industry had really … taken off.

Region where ash concentration exceeds threshold within 24 hours following individual eruption - Leadbetter and Hort (2010)

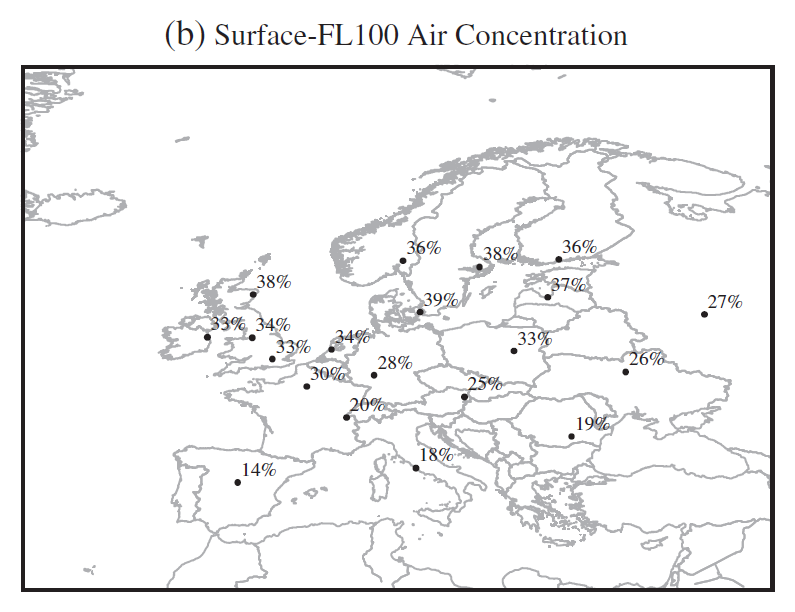

Finally, they plotted the probability of 20 different European airports being affected by ash in the 4 days following the eruption. As expected, Scotland and Scandinavia come off worst, and it seems that all of the UK has about a 1 in 3 chance of being affected by a Hekla eruption of this type.

Probability that ash concentration exceeds threshold within 4 days of eruption at various European airports - Leadbetter and Hort (2011)

Volcano roulette

Combining the numbers above, we can estimate the probability of an eruption affecting UK airports in any given year. But before doing so, there are a number of factors to consider. The most important are:

- Not all eruptions are equal. Icelandic eruptions can vary in size, duration and the amount of ash produced. For example, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption had a lower plume (~9 km) and eruption rate, but lasted much longer (~4 days for initial explosive phase) than the Hekla eruption here. All these factors will affect the risk to the UK.

- The Met Office study was carried out before the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, when the advice for aircraft was to avoid all ash. This was good advice; the United States Geological Survey recently found that ~20% of reported aircraft-ash encounters since 1953 had resulted in engine damage or failure. Since 2010, a new threshold of 2 milligrams per cubic metre has been introduced. This is higher than the threshold used in the study, so it is less likely to be exceeded.

These factors add uncertainty to any calculations, which currently provide only a rough estimate of the probability of a UK airport being affected by ash from an Icelandic eruption in any given year. The probability is calculated as:

P = chance of eruption (1/5) x proportion of eruptions that produce ash (3/4) x probability of ash reaching the UK (1/3) = 1/20

Taking into account the uncertainty added by the factors above, it is fair to say that we can expect airport closures about every few decades. This is quite a simplistic calculation, but the take-home message is that this is not just a once-in-a-millenium, or even a once-per-century event. Consequently, it is something that we should be planning for and working hard to understand.

Thanks

This is the first post at volcan01010, and the combination of Iceland, volcanoes and computing is a good taster of things to come. I’d like to thank Chris and Anne at all-geo.org for hosting this blog and giving me somewhere to write it!

As an agronomist working on my Ph.D. I am delighted to read scientific material where numerical methods are used to predict the probability of events. I remember hearing about the airport shut-downs from volcanoes in the media and hearing alarmist rhetoric about “the Earth coming to an end” but, I figured, there is a reasonable explanation for this phenomena. Thank you for using a scientific approach for to communicate reason.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Ash cloud closes UK airports: what are the chances? | Volcan01010 -- Topsy.com

Pingback: A new blog at All-geo: Volcan01010 | Highly Allochthonous

Fantastic post but I was wanting to know if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Thanks!

rXGDd4 Good point. I hadn’t thought about it quite that way. 🙂

Pingback: Grímsvötn 2011 (Part 1): UK ash deposition from the biggest Icelandic eruption since Katla 1918 | Volcan01010

Pingback: Grímsvötn 2011 (Part 2): Effects on aviation of the biggest Icelandic eruption since Katla 1918 | Volcan01010

Pingback: A history of ash clouds and aviation | Volcan01010

Pingback: Alaskan ash in Ireland: context, implications and media coverage | Volcan01010

Pingback: How big are the grains in a volcanic ash cloud? | Volcan01010