Just 100s km away from you are right now there is a place where rocks can flow, where once-living matter is turned in jewels, from where deadly plumes once killed nearly all life on earth. We can never visit this place – even though it’s right under you.

1. Human beings will never reach the deep earth

We’ve been to the moon and Mars is almost in our reach but we are never going to the deep earth. The deepest hole ever drilled got just over 12km below the surface – that’s a paltry 0.2% of the 6380km to the earth’s centre. It gets harder to drill the further you go. The rock was already 180°C when they stopped drilling and it gets hotter as you go down, getting as high as maybe 6000°C (as hot as the surface of the sun).

We could *maybe* send a probe down there. In a paper in Nature, David Stevenson came up with the most plausible plan to date. It involves making a crack in the earth (with a nuclear explosion) and filling it with 100,000 tonnes of liquid iron and a small probe. The probe (might) then sink down to the edge of the earth’s core. No-one is planning to try this out at the moment, but it would make for an interesting Kickstarter project.

There is a lot of heat in the earth. Consider that scene in Star Wars when the Millennium Falcon comes out of hyperspace and finds just spinning rocks where Alderaan used to be. If a Death Star destroyed earth you wouldn’t get an asteroid belt immediately afterwards, instead you’d get a extremely hot cloud of liquid, or even vaporised rock. Even Han Solo would have trouble dodging that.

2. A spinning ball of molten metal

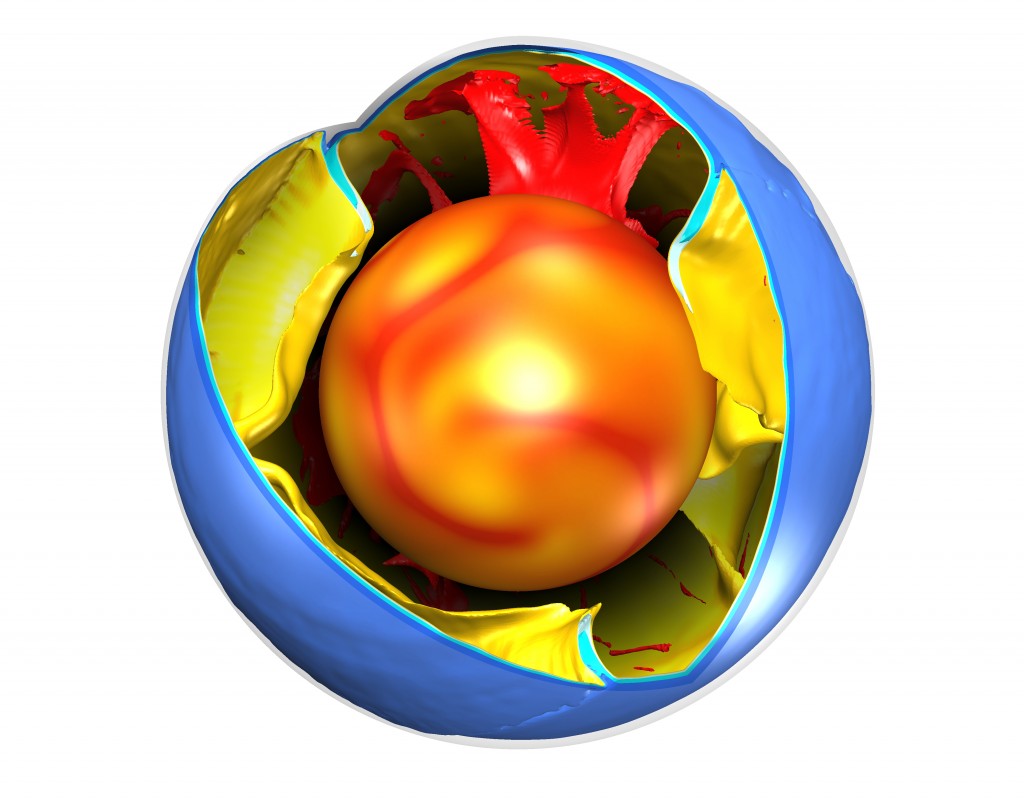

The earth’s structure is a bit like that of a peach. There’s a thin skin, a thick juicy layer and a core that’s surprisingly large and totally different from the stuff above it.

We are the thin layer of mould on the surface of our giant peach. The skin is the earth’s crust (that we can’t even drill through). The bulk of the earth is called the mantle and its made up of a dark heavy rock called peridotite. We can never get to the earth’s core, but we know (from indirect observations and by analogy with meteorites) that it’s made of iron and nickel – totally different from the silica-rich rock above. The outer layer of the core is molten, but at the very centre of the earth its solid, made out of giant crystals of iron and nickel.

The spinning liquid outer core produces the magnetic field that twists your compass and tells dogs which direction to pee in. One way to understand the core better is to simulate it in the lab, by creating a giant sphere containing spinning liquid sodium. It’s also a good way for scientists to look a bit more like Bond villains standing next to their super-weapon.

3. You can’t handle the pressure!

It seems counter-intuitive. The earth gets hotter the deeper you go, yet the outer core is molten and the inner solid. Normally things melt when they get hotter, so why is that?

Pressure.

We’re familiar with the fact that pressure increases in the deep sea, as there is a lot of water above, pushing down. It’s the same in the earth, only rock is heavier and there are thousands of kilometres above, pushing down.

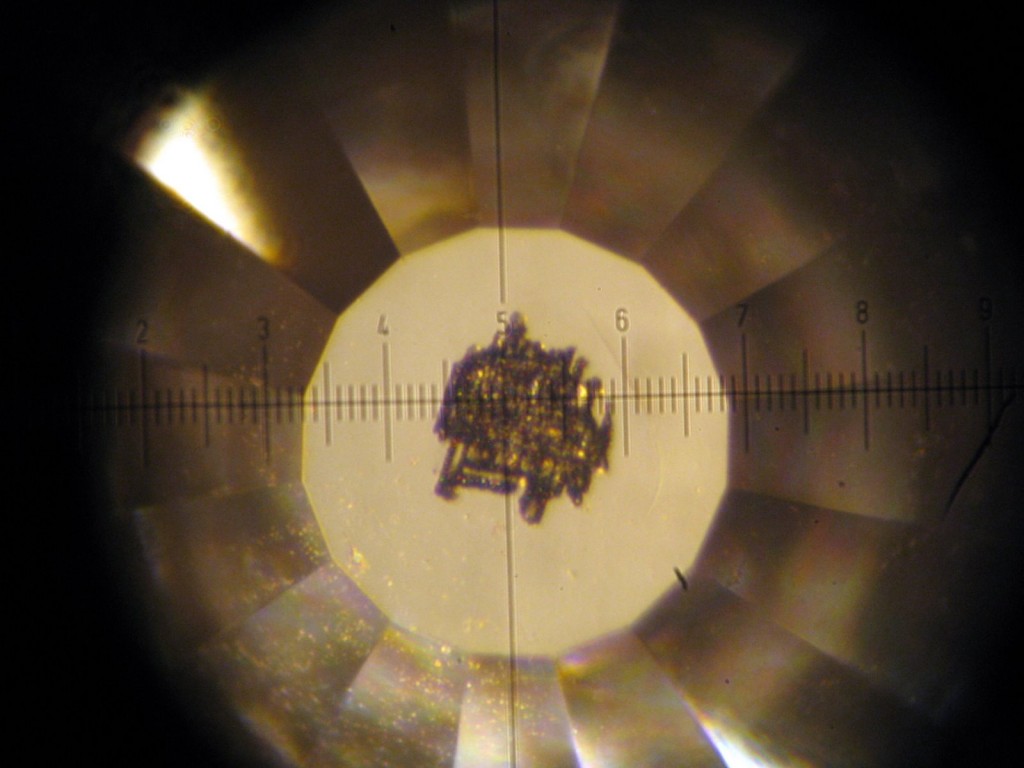

The pressures get so intense that the only way to reproduce them in the lab is to take an tiny unfortunate sample of rock, put it between two diamonds and squeeeeze. To reach the required temperatures, you also fire lasers at it, through the diamonds. Occasionally the diamonds can’t handle the pressure and they explode, sometimes popping loudly or emitting a flash of light.

Under high pressure, it’s easier for materials to be solid rather than liquid, as the atoms prefer to be tightly packed together. The metal in the earth’s core is solid at the centre because the pressure is higher there.

4. Solid rock that flows

We know from listening to earthquake waves that pass through it that the earth’s mantle is solid. It’s incredibly hot, but the pressure means that – give or take a few percent in places – there is no liquid rock down there.

Knowing this held back acceptance of the idea that continents move. The geological evidence was known, but it was thought that continents couldn’t move because they were attached to the mantle and ‘solid rock can’t flow’. Only it can.

Hit a piece of the mantle with a hammer and it will break (or break your hammer – it’s tough stuff). But heat it up and push it the same way for millions of years and it will flow. It’s made of crystals, endless ranks of atoms lined up in rigid patterns. Tiny gaps in these patterns allow atoms to slip past each other and slightly change the shape of the crystal. Countless of these tiny steps, in myriad of crystals over millions of years allows the earth’s mantle to flow, convecting in majestic patterns driven by heat leaving the earth.

Patterns of plate tectonics on the surface are driven by this flow. The most dramatic example being subduction, where crust sinks down into the mantle, sometimes sinking deep down to the edge of the core.

5. Death from below

The link between meteorite impacts and mass extinctions is well known – the image of a dinosaur looking up at an incoming fireball is almost a cliche. However some scientists think they should be looking down, and that the deep earth has caused more extinctions than impacts have.

The event that did for the dinosaurs, at the end of the Cretaceous (66 million years ago) is just the most glamorous of many mass extinction events. The biggest was at the end of the Permian (252 million years) – up to 96% of marine species became extinct. There is no good evidence for a meteorite impact at the end of the Permian, but there is a huge pile of lava, covering much of Siberia. This was caused by a massive mantle plume, a column of hot rock that started at the base of mantle.

To kill nearly anything you need to foul the sky and poison the seas. Volcanoes give off noxious gases which in normal amounts don’t cause problems. But covering 2 million square kilometres of land in lava is not normal. However it was done – by pumping out massive quantities of ash or by producing carbon dioxide by burning nearby coal deposits (or some other way) – the link between mantle plumes, lava and death seems pretty certain.

The end-Cretaceous extinction saw a meteorite impact, but it also saw a massive outpouring of lava from the mantle, this time in India, at exactly the same time. There are those who argue that the death of the dinosaurs is as much due to the deep earth as it is a rock from space.

6. Visitors from the deep

A lot of what we know about the deep earth comes from indirect measurements, like when a doctor uses a stethoscope or MRI scanner to ‘look’ inside your body. But sometimes to know what’s really going on you need a direct sample from deep inside – a biopsy. To do this for the heavenly body we sit on – in other words to perform a geopsy1 – you need a special kind of volcanic rock. When some molten rock rises from the mantle, it contains crystals that were formed at depth, but carried up in it. The most interesting, most glamorous, most beautiful, and most valuable of these exotic visitors are diamonds.

I could go on about diamonds for a long time (in fact, I already have) but forget that they can be made billions of years old, and may contain traces of an ancient oxygen-free atmosphere, instead let’s focus on the fact that some diamonds contain carbon that was once part of a living thing.

When carbon has passed through a process of photosynthesis, its isotopes have a distinctive pattern . Finding this ‘light carbon’ in diamonds allows us to tell an amazing story. Something was once alive2, died and formed black mud on the ocean floor. This was then forced into the mantle where it sank deeper and deeper. At some point the carbon started flowing up (as part of some sort of fluid) and got pulled into a growing diamond which then got caught up in some fizzy magma that, within hours or days, pushed up to near the earth’s surface, where humans could find it and marvel.

Human beings can never reach the deep earth. Alive. The carbon in our bodies might though. Just arrange to die and get buried in the right bit of the sea bed and part of you might one day end up in the deep earth.

References

What to know more? Don’t believe these amazing facts are true? Either way, read these links for more details.

The idea of how to get a probe into the deep Earth come from a pukka scientific paper.

The Death Star isn’t really real (honest), but scientists model the liquid/gas rock that would happen if the earth was destroyed when they model a collision with another planet. Something that may have happened long ago to create the moon.

If you want to see that huge sphere containing liquid sodium in action, see it here.

My information about exploding diamonds came from Mary Panero, who is on Twitter @mineraltoPlanet

All you ever wanted to know about the Siberian Traps and the end-Permian event can be found on a great Leicester University site.

Scientists who believe mantle plumes rather than the meteorite killed the dinosaurs point to evidence from India. The lava (known as the Deccan Traps) is seen to happen at the same time as the extinctions, but the layer of Iridium enrichment comes after the extinction. More details here.

More more information about diamonds, there’s a useful recent review of the science.

1 comment

Comments are closed.