Some towns have all the luck. A thousand years ago Southwold, in Suffolk on England’s east cost, was a fishing village dwarfed by Dunwich, a major port town to its south. Nowadays Southwold is a thriving seaside town and Dunwich is just a few houses, one pub and a museum. Its priory, leper hospital and over 8 churches are all gone – swallowed by the sea.

Geologically England’s east coast is part of the North Sea basin. In the Dunwich / Southwold area the bedrock is the Crag group – sands formed up to 5 million years ago in shallow seas. These are only weakly lithified – as much sand as sandstone – and so basically identical to the banks of sand found offshore today. The area is extremely flat, the photo above was taken at only 15m above sea-level but gives a clear view over 10s of kilometres horizontal distance.

This adds up to a landscape that was formed by the North Sea and which can be transformed by it. Seas move sediment around all the time. Tides, waves and especially storms can move massive quantities of sand and gravel to and fro, in often unpredictable patterns. What happened to Dunwich is geologically unremarkable. Over 1000 years a 10-20 metre thick layer of sediment was eaten away and moved elsewhere on the seabed. If this happened offshore, we’d barely notice, but 20 metres can be a long long way – vertically its the distance between a seaside pub and a sandy sea-bed. In human terms these places could hardly be further apart.

The first historical mention of erosion at Dunwich is found the in the Domesday book. Written in 1086, this survey ordered by William the Conqueror of his new kingdom, describes a town that had been important for over 500 years. As an important port and fishing village Dunwich owed a lot to the sea , it was a place where feudal dues could be “£4 and 8,000 herrings”. Already it was clear that land was being lost: “Then [there were] 2 carucates of land [one carucate equals 120 acres], [but] now one; the sea carried off the other.”

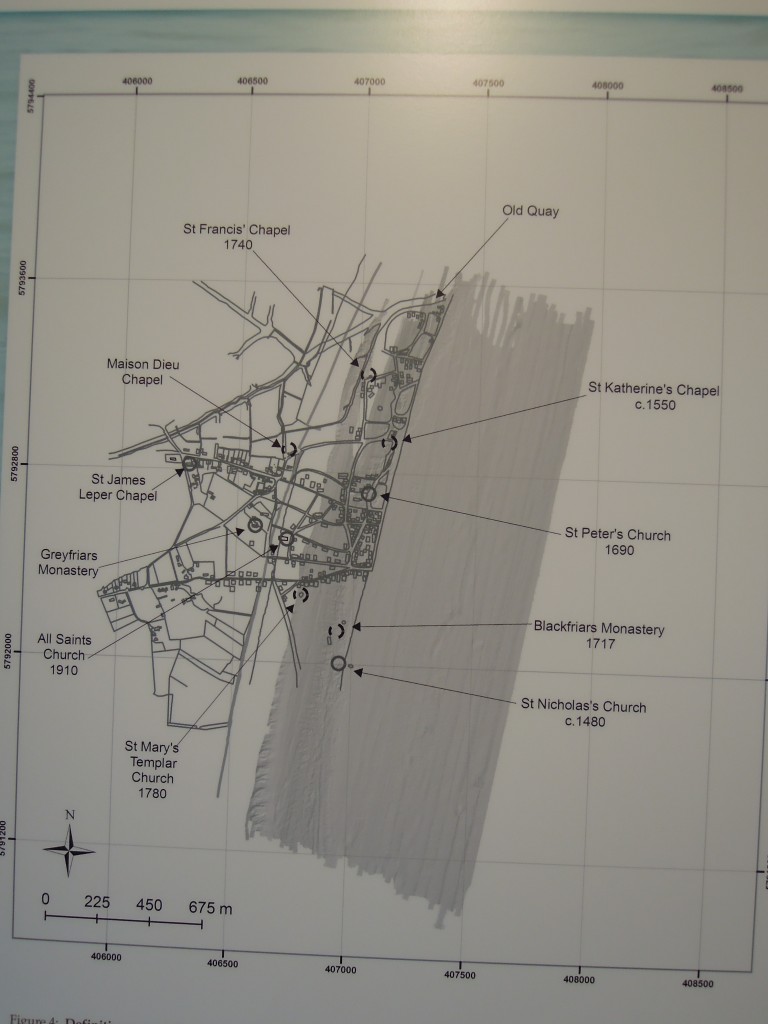

The sea started to ‘carry off’ a lot more land in the next 1000 years, at an average rate of a meter a year. This rate wasn’t steady. If storms, tides or winds pull together, sudden and dramatic changes can happen. In March 1286 a strip of land up to a hundred metres was washed away, destroying churches, houses and lives in the process. January 1328 saw high tides, storms and further destruction.

Over this same time, movement of sediment above sea-level caused another serious blow to the town. Dunwich’s wealth and importance was based on its harbour, centred around a large area of calm water where the end of the river Dunwich was protected by a large shingle bank called “Kings Holme”. The river Blyth, that passes between Southwold and Walberswick also sat behind the shingle bank, which meant it reached the sea near Dunwich. Ships from Walberswick therefore had to pay tolls to Dunwich for the right to reach the sea. The two communities did not get on.

In 1250 Kings Holme extended south so as to completely cover the harbour mouth at Dunwich. The rivers found a new exit to the sea near Walberswick, which would mean Dunwich ships paying tolls to Walberswick. Unwilling to accept this change in fortune, the people of Dunwich dug a channel to the sea through their town and forced the closure of the Walberswick gap, creating much ill-feeling. The storms of 1328 finally blocked the Dunwich channel. Since then the low land behind Kings Holme has silted up and it is now ‘marsh’ filled with reed beds. The river Dunwich still reaches the sea at Walberswick, running north parallel to the coast for 5 kilometres.

The events of 1328 saw the beginning of the end for Dunwich. Slow decline followed as people left and the sea kept nibbling away.

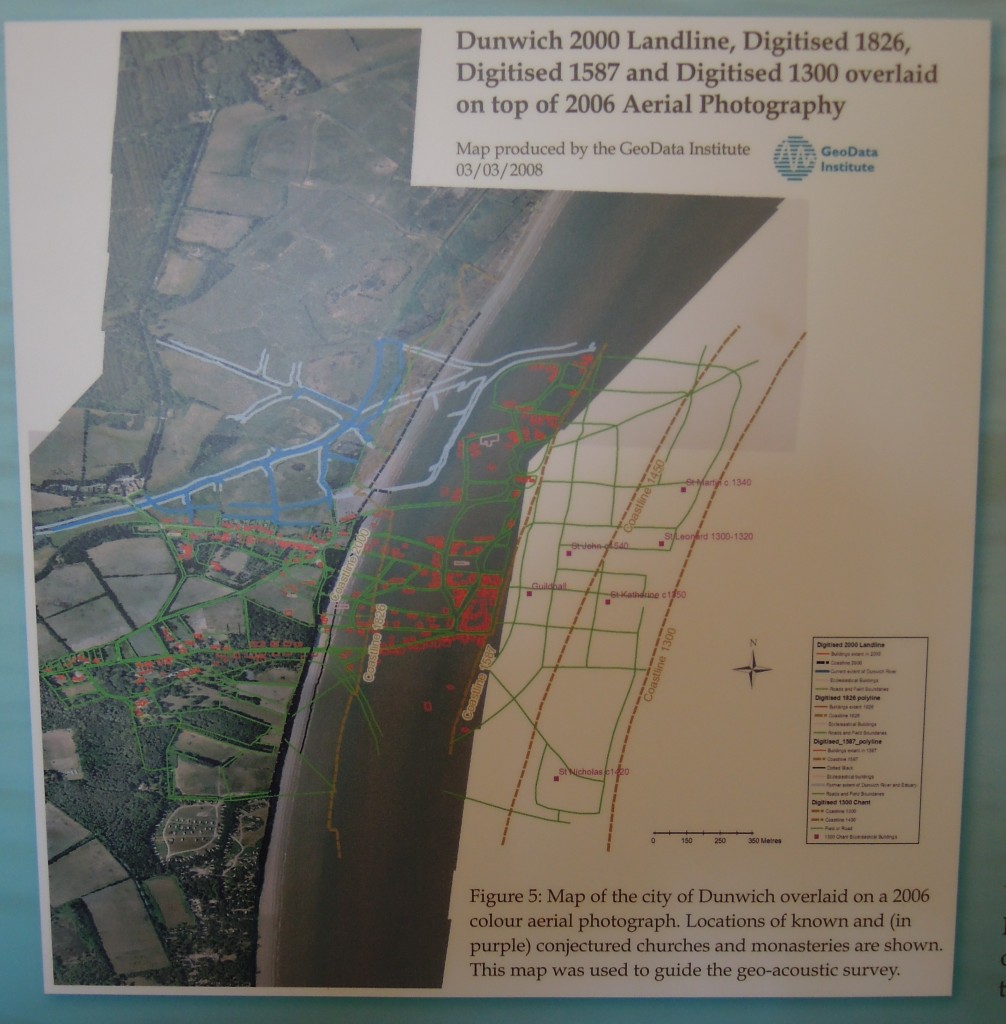

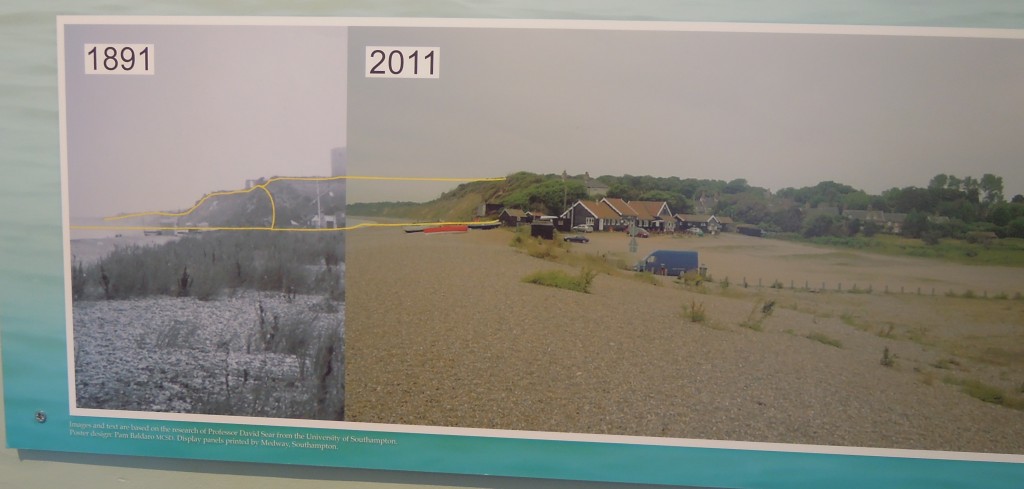

As we get nearer to the present time, the detail of Dunwich’s destruction becomes clearer. With the advent of photography, we can move from maps to pictures.

Dunwich today is an odd place. The beach is steep shingle, with some miserable looking cliffs made of soft sandstone.

Its a worn-down stump of a town, but is enlivened by its past. The museum is excellent and well worth a visit. The area is of great archaeological and historical interest, with groups studying the remains on the sea-bed and other sites discussing the history. One bonkers idea I quite like (which will never happen) is to stick metal poles in the sea-bed, to create a sculpture above the sea showing where the churches once stood.

Today Southwold is the clear winner in the battle of the towns. It has a pier, a lighthouse, a brewery and a sandy beach surrounded by beach-huts. Once described as being like “the 1950s, but with olives” it combines timeless charm with modern gastronomy. Affluent urbanites (like me) come to enjoy the sea-side experience, complete with local pork pies and beer.

Southwold even beats Dunwich for history, as its mediaeval church remains. As a relative backwater for 600 years, Suffolk churches contain many 14th and 15th century features, like painted rood screens covered in colourful pictures of saints. In most of England these Roman Catholic features have been completely removed during the last 500 years of Protestantism. In Suffolk they were (literally) defaced by Protestant reformers in the 16th and 17th centuries as being ‘idolatrous’, but apart from these rough chisel marks they remain untouched, a glimpse of a former world.

I love visiting the Suffolk coast, but I wouldn’t buy a house there. Modern studies of coastal dynamics suggest that while Dunwich and other areas will continue to be eaten away, Southwold and the nuclear power stations at Sizewell are safe, for now at least.

These studies work on an engineering timescale. Even if they have fully factored in the impact of increased sea-level and more intense storms that we expect a warmer future to hold, they still only deal with time-scales of decades. To a geologist, places like Dunwich are a reminder of the small scale of human activity. Sea levels will change, sediment will move, coasts will shift. Whether a town benefits or suffers from this is out of our control, as the people of Dunwich learnt to their cost.

The small human timescale of this erosion is also backed up by Dunwich’s political history – in the late medieval period it was prosperous and populous enough to be a borough returning an MP to Parliament. By 1831 that population had eroded so much – along with the coastline – that there were barely any voters left, and Dunwich was fingered in the Great Reform Act of 1832 as a rotten borough – ie one which not longer deserved its status as a constituency compared with, say, those tiny places like Birmingham or Manchester.

PS I actually like the idea of the metal pole sculpture showing the churches in the sea…

Si,

I’m sure you are aware of it – but if not, this website – http://www.dunwich.org.uk/ contains some pretty nifty geophysical survey imagery of the ruins of Dunwich (and I’m not flagging it just because I had some small involvement in the project :))

Hi Daffyd,

I linked to it above, but it probably does deserve more prominence.

Si

Doh! I didn’t click on the links …

I am gradually building a blogsite of walks in Suffolk, amongst others, and will link to this very interesting information. Thank you