Author Tim Robinson spent countless hours in the west of Ireland, unearthing local Irish-language place names. Some are anchored in myth and poetry, referring to miracle-working saints or Celtic Gods. Most though are prosaic, being linked to people’s names, local plants or animals and – occasionally – geological features.

Fàire nan Clach Ruadha is one of the countless hills within Assynt’s central wilderness, just another small summit amid the craggy wastes of the Cnoc and Lochan landscape. Once I’d roughly translated it as ‘red stone lookout’, I knew I had to pay a visit. Secretly I was hoping the ‘red rocks’ would be garnet-rich, as is often the case within the Lewisian Gneiss.

On a perfect June day I went in search of the physical realities behind the name. Let’s start with ‘Fàire’. The online resources I’ve used translate this as ‘watch, lookout’, which implies someone once sat on the top of the hill, keeping an eye out for something. This could have been livestock: sheep or cattle. Subsistence farming practices saw animals brought into the interior during the Summer, to make use of the good grazing found here and keep them away from arable crops. Ruins out here are often Shielings, simple buildings built for Summer use only. We are not far here from some and the hill offers good all-round views of the immediate area.

So maybe previous visitors were enjoying themselves, having a relaxed Summer just like me. Tim Robinson translates the Irish phrase for a nostalgic return: “Cuairt an lao ar an athbhuaile” as “the calf’s visit to the old milking place”, a reference to the practice of taking livestock into the hills in Summer. This booleying (to use the Irish terminology) lasted until the 1930s in Ireland and Robinson quotes some idyllic sounding memories of those times.

There is another possibility. Walking inland, this hill is the first to give really distant views of the sea, to raise you above this land’s crinkly corrugations. In the photo above you can see the Achiltibuie peninsula, top left, about 10 km distant. The faint smudges of the Outer Hebrides are clearly visible to the naked eye. Maybe this was a place to look out for ships. There are Norse-inflected names are present near here – Suilven and Inverkirkaig for example. Could a lookout here once have run off in terror, sprinting to give advance warning of a hostile Viking attack? On a glorious June day it seems like an impossible idea. Surely a dot on the horizon would cause joyful anticipation of a returning loved one, home from the sea.

What of the “red rocks”? While the bedrock of Fàire nan Clach Ruadha is made of Lewisian Gneiss, blocks of red Torridonian sandstone are found in great abundance here littering the surface. Some sit proud on the top of the hill, but the most abundant areas are on west-facing slopes.

As for much of Assynt, photos taken from here become dominated by the great charismatic peaks of Suilven and Stac Pollaigh. Like being photo-bombed by a celebrity, they immediately become the focus of the image, demanding your attention through sheer charisma. These peaks are also made of Torridonian sandstone, so on Fàire nan Clach Ruadha it feels like they are proud parents, peering down upon their tiny offspring.

Imagine this is how mountains form. The big parent mountain silently urging its offspring to grow up big and strong. Perhaps they are like sharks, the biggest feasting off their siblings in a race to reach adult size. I could be in the midst of a massacre, too slow to register on human timescales.

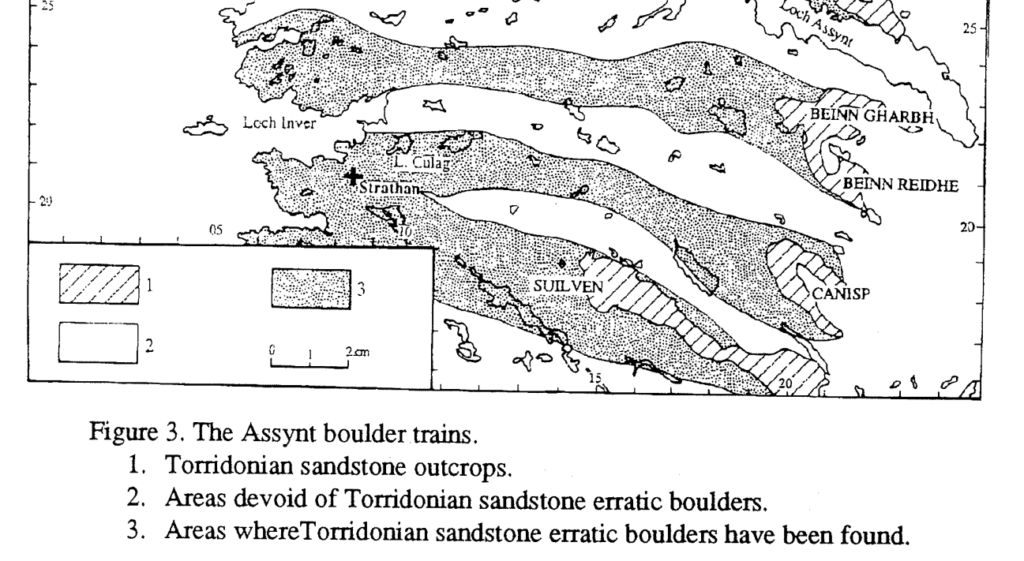

Of course this is actually how mountains die. Each block was plucked from the side of Suilven by ice and left behind by a now vanished ice sheet. We know this, as people have laboriously mapped the location of these ‘boulder trains’ of Torridonian sandstone, showing a clear link.

Fàire nan Clach Ruadha is within the boulder train coming from Suilven

This academic paper ends with a great acknowledgements section, thanking “the unstinting, though often forced, efforts of a large number of A level Geography students ….helped in the plotting… across this knurled and unyielding landscape, often in the most unhelpful of weather“.

Place names are echoes of how past generations have engaged with a landscape, a reminder that our feet are not the first to tread these rocks. Subsistence farmers on a lazy Summer’s day; somebody anxiously scanning the sea; wet and grumpy teenagers; maybe all have noticed these red rocks before me.