Standing on the shores of Loch nan Uamh I was feeling distracted. There was a lot to attend to. Behind me was a flat strip of grass, growing on a beach deposit now left high and dry by the crust’s slow straightening of its spine after the weight of a huge ice cap melted away. Perched above the fossil beach was a Victorian country house where incredibly brave people from across Europe had trained before being dropped into Nazi-occupied Europe to wreak righteous havoc. To my left sits an Iron age hill fort and straight ahead a sublime view demanding I pay attention to its wild empty peninsulas, small forested islands and wide rolling sweep, all under a cloudless sky. The drift of my thoughts towards why this landscape is so wild – heartless landlords and ‘improvement’ leading to clearance and gaelic songs sadly sung on a ship to Canada – is interrupted by my family. Not unreasonably they want me to stop staring into space and attend to their games on the rocky beach.

Fatherly duties still leave time for me to assume the geologist’s pose and stare at the ground, assessing the cobbles at my feet. I snaffle a nice bit of granite first. Then a nice piece of pinkish folded quartzite catches my eye and slips into a pocket to be forgotten as the glorious day rolls on.

You can see how it caught my eye. Just short of a billion years ago it was formed as different layers of sand, some nearly pure quartz, others more muddy. It’s since been heated and squashed within the earth. The quartz is still quartz but the mud is now shiny mica.

What were once flat layers 1 are now folded. The pattern we see is the intersection of a 3D fold with the complex rounded surface of the pebble. Call the image above as a view of the top of the pebble. Let’s rotate it round (it sits beautifully in the hand, like a heavy cricket ball) and look at one of the sides.

These sigmoidal shapes are classic folds. You can almost visualise the rock sitting in a clamp being squashed horizontally to turn flat lines into wavy.

Rotate the sample 180 degrees around a vertical axis to see the other side of the sample and you see the same folds coming out of the other side of the rock.

Looks simple. But appearances can be deceptive. Let’s rotate the sample to look at its underside (the side my thumb is holding in the picture above).

At the top of this photo you can see some of the edge in the preceding picture. So the folds we’ve seen before have their crests and troughs running vertically through the image. You can see that, but not just that. The darker layer sitting in the middle of the shot runs from top to bottom, marking a trough in the folding, but it is forming a rough cross shape, not a single line as I would expect.

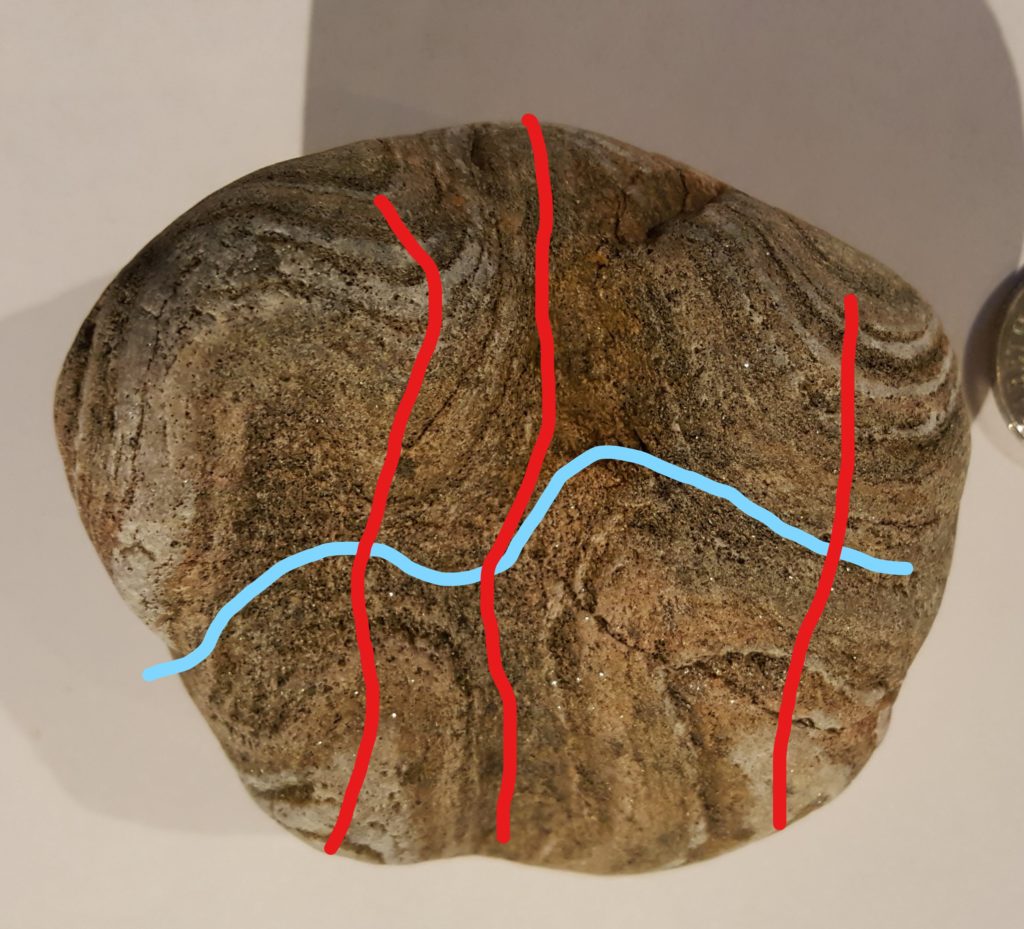

There are two sets of folding in this sample. I’ll try and annotate that for you.

In red I’ve drawn most of the troughs and peaks of the main folds. The ones we’ve seen now from three angles. The blue line shows what I reckon is an earlier fold, where the crest of the trough is itself folded by the red folding.

Here’s a view looking at the side again, the edge on the right side above. It’s at an angle of 90 degrees to the other side views. We are looking down on a trough shape made by the earlier blue folding, now bent around by the red folds.

Here are some oblique views in the same direction, that makes the saddle shape formed by the two sets of folding more obvious.

This stuff is hard to see from photos. It’s easier to visualise the three-dimensional patterns when you’ve got the sample in your hand, but even then I didn’t notice (distracted as I was) the full complexity when I first picked it off the beach.

This stuff is hard to see from photos. It’s easier to visualise the three-dimensional patterns when you’ve got the sample in your hand, but even then I didn’t notice (distracted as I was) the full complexity when I first picked it off the beach.

The rock sample is probably from the local Moine rocks, where refolded folds are common. There’s a bigger and more complicated example in the hills above where I collected this a tale of past oceans opening and closing, lost continents forming and splitting. But we’ll come to this in a future post.

Having retired a few years ago, I’m catching up on courses I took as an undergraduate in the late 1960s — including Geology 101. More than once I’ve wished I’d majored in the subject, if only to develop a geologist’s eye — the capacity to see patterns that are utterly invisible to others. This post opens that vista to the uninitiated, and I really liked it. Thanks!

Thanks for sharing

Would you say this is a small example of a type 1 polyphase fold?

Yes. I couldn’t be bothered to look up the definition when writing the post but you’re right. The two sets of fold axes are vertical wrt to the bedding and roughly at right angles.

The other types have recumbent folds where the layers and fold axes are parallel.

Anyone not knowing what I’m talking about, have a look here:

https://www.see.leeds.ac.uk/structure/folds/polyphase/index.htm

I am all that much satisfied with the substance you have said. I needed to thank you for this extraordinary article.