Here in Cadiz, I’m surrounded by death and I don’t mind at all.

It’s the geologist in me thinking this – in every other way this is a lovely life-affirming holiday. It’s just that every surface seems to be filled with the remains of long-dead animals.

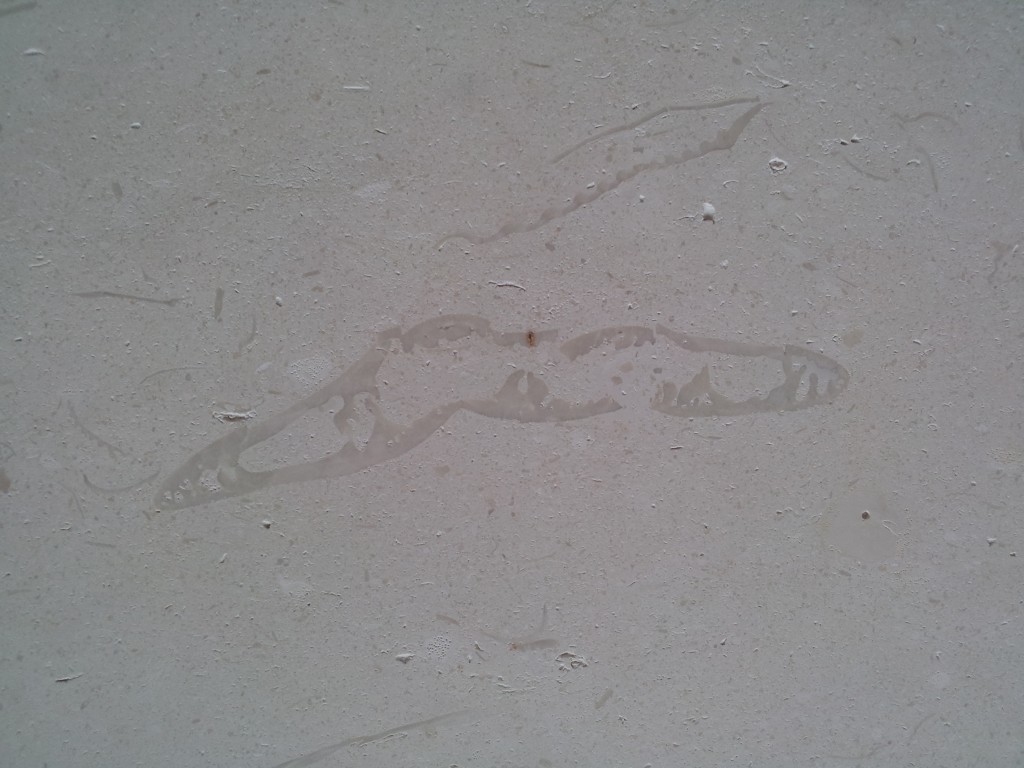

The floor and one wall of the hotel room in which I’m sitting is covered in a fine white limestone packed with the remains of fossils – mostly bivalves. There are thick finely layered oyster shells and finely ribbed shells that remind me of scallops. The stone has mostly been cut perpendicular to bedding so the shells are seen in cross-section. These elegant fine grey lines are within a lighter matrix that – on closer inspection – is made up of smaller pieces of something-that-once-was-alive-and-now-is-not.

This is of course a wonderful thing. To be surrounded by traces of an ancient sea-bed, as productive and vibrant as any modern tropical sea and to live in a time that fully understands that significant of these little grey squiggles is indeed a privilege. But they are still dead.

Leaving the room doesn’t help. The city of Cadiz seems largely built from the local rock. This is basically a pile of shells bound together with ground up shell and maybe a little brown sand.

Cadiz is great for seafood, there were men with buckets of sea urchins and big knives wandering around earlier. Imagine a seafood restaurant kitchen at the end of the evening: there’s a pile of shells somewhere – big chunky oyster shells, purple fragments of bust-open sea urchins, maybe a few spiny sea snails. If you laid them out in a layer they’d cover a few tables maybe, not more. If an eccentric restaurant owner made a pile in his garden, after a year it would be pretty big (and very smelly). Archaeologists call similar features shell middens and given thousands of years, greedy people can make piles that are kilometers long and meters thick and wide. The layer of stone that old buildings in Cadiz are made from covers a much wider area – it’s not just a strip along the coast – so it must be thousands of times the volume.

Cadiz is great for seafood, there were men with buckets of sea urchins and big knives wandering around earlier. Imagine a seafood restaurant kitchen at the end of the evening: there’s a pile of shells somewhere – big chunky oyster shells, purple fragments of bust-open sea urchins, maybe a few spiny sea snails. If you laid them out in a layer they’d cover a few tables maybe, not more. If an eccentric restaurant owner made a pile in his garden, after a year it would be pretty big (and very smelly). Archaeologists call similar features shell middens and given thousands of years, greedy people can make piles that are kilometers long and meters thick and wide. The layer of stone that old buildings in Cadiz are made from covers a much wider area – it’s not just a strip along the coast – so it must be thousands of times the volume.

This is where deep time comes in. My simple thought experiment suggests that the stone that Cadiz is made of took millions of years to form. Similar thinking by 19th Century geologists revealed the unsettling scale of geological time and set the scene for Charles Darwin to formulate his theories. Over these timescales tiny steps can make enormous changes, just as piles of small animals can be used to build a city.

Deep time can be unsettling: what will the remorseless grinding of the years do to us and our achievements? Will everything and everybody you know be reduced to a few odd layers and a puzzling mass extinction? Maybe. Nobody knows. But my life is enriched by knowing my place within the wider framework just as my walk to the restaurant this evening will be enlivened by spotting the oyster shells in the wall.

I am with you on the wonder of fossils.

Pingback: Rythm, Light & Colour – Dianne and Kent's 2018 Travel Adventures