Fracking is rightly a major political issue. In Britain this is topical as the government has just released a technical report showing that very large volumes of natural gas are locked into rocks beneath northern England. As a tax-payer whose house is heated and food cooked using gas, but who is concerned about CO2 emissions and climate change, I will be directly affected whether we extract this gas or if we leave it be. But what interested me about the report was not politics, not energy policy, but a genuine pride in the quality of unbiased scientific data contained within it. Politics can wait. Let’s celebrate the vast data sets and clear and comprehensive analysis that I’m glad my taxes have paid for.

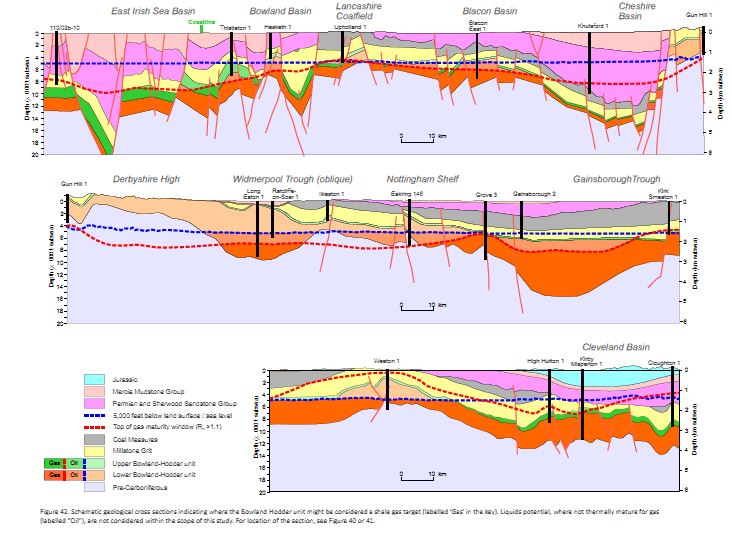

Figure 42, schematic cross sections of the north of England. Copyright DECC 2013

The report sits in a clean and fast web-page, linking to downloadable reports that include a vast amount of data. It’s copyrighted, but I can copy images into here, with attribution. There’s even an apologetic note that ‘users of assistive technology’ may not be able to make use of the files. This is how all government websites should be.

The study focuses on a particular geological unit that covers much of the north of England, the Bowland-Hodder shale. For a geological introduction, I can’t better the report itself: “Marine shales were deposited in a complex series of tectonically active basins across central Britain during the Visean and Namurian epochs of the Carboniferous (c.347-318 Ma). …. The marine shales attain thicknesses of up to 16,000 ft (5000m) in basin depocentres (i.e. the Bowland, Blacon, Gainsborough, Widmerpool, Edale and Cleveland basins), and they contain sufficient organic matter to generate considerable amounts of hydrocarbons.”

The study identifies draws on a mass of seismic and borehole data and distinguishes two horizons, an upper and a lower. The upper is a post-rift deposit that resembles “prolific North American shale gas plays”. The lower is less well known (not much drilling information) but was deposited during the rifting and so is a thicker deposit. Here’s a sense of how much data they are drawing on:

Figure 8. Copyright DECC 2013

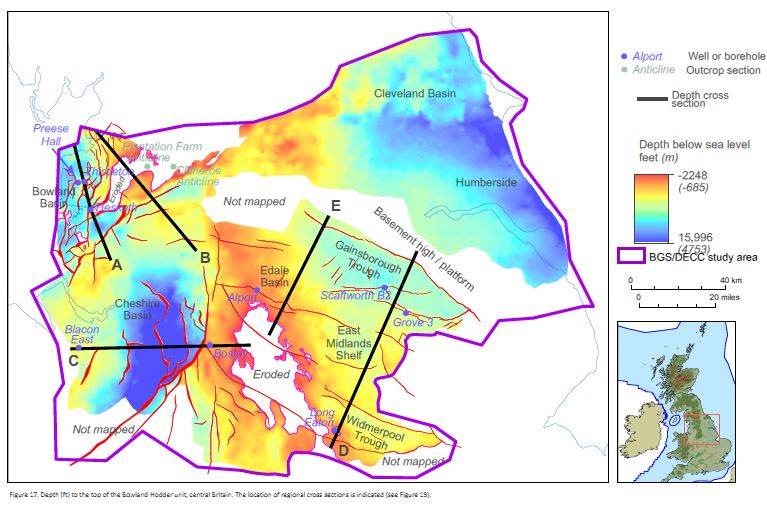

Seismic data gives you a cross-section view through the sedimentary layers. Borehole data allows you to link the layers to actual rocks. Gamma ray logging data allows you to estimate the amount of organic matter within these rocks. The report tells you how the deep the shale is:

Figure 17. Copyright DECC 2013

It has other pretty maps showing how thick the layers are, plus lots of cross-sections.

These rocks started as mud with organic matter in them. This only turns into valuable oil or gas once that organic matter has been buried and heated. The shininess of woody matter from boreholes (called vitrinite reflectance), records how much the rocks have been heated. Particular values of vitrinite reflectance correspond to a ‘gas window’ indicating that shales with organic matter are likely to contain methane gas.

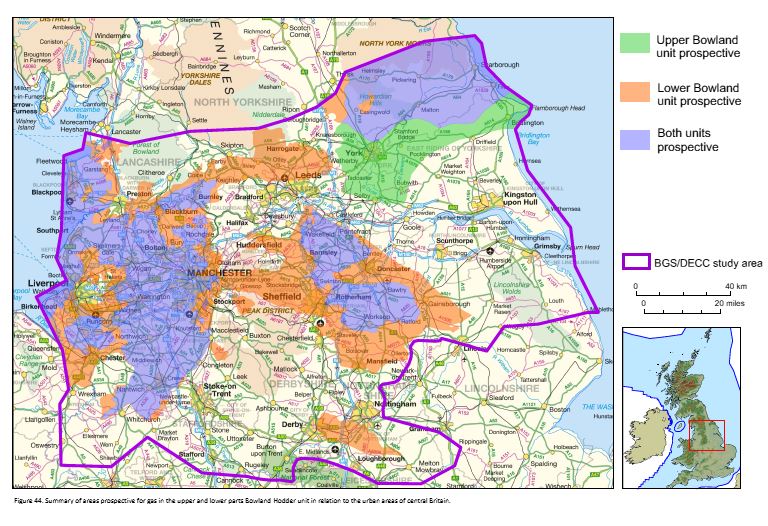

Putting all this data together, the British Geological Survey guys have produced maps of areas where the upper and lower units exist and have passed through the gas window.

Figure 44. Copyright DECC 2013

What the man in the street wants to know is: how much gas is there? The study uses a Monte Carlo analysis of the various parameters to come up with an estimate. In layman’s terms, there is an enormous amount – around a quadrillion cubit feet. Even allowing for the fact that fracking can only extract a small proportion, the amounts are easily comparable with the conventional gas reserves already extracted from the North Sea.

I’ve barely scratched the surface of the data contained in these reports. I’m sure there are many geologists employed by industry studying them intently, but note that as far as I can tell, all of this data is provided by the British Geological Survey. Will this report result in many more holes being drilled into the north of England? Only time will tell.

i dont understand

So basically their north is our middle