Geology is such a great thing to study because it involves making so many connections through time and space, switching scales from the cosmic to the atomic. This means that challenge for this series of posts about the geology of the west of Ireland is going to be managing scope. So. Although I could start with the big bang, I won’t. I’ll start with the Dalradian.

A thick package of sediment, the Dalradian Supergroup, or just Dalradian, to its friends was was named in the 19th century after Dál Riata a minor kingdom in 6th and 7th century Scotland. Dál Riata was an Irish colony within Scotland, appropriately, as Dalradian rocks are found over much of Highland Scotland and NW Ireland.

A Celtic Supergroup

To fans of 1970s Prog Rock, a supergroup is a band formed from musicians who made their names in other bands. For geologists, it means a bunch of groups that are bound together, a group being a large recognisable package of sediment. The groups usually sit on top of each and represent a period of time during which sediment was deposited. For both types of supergroup, the individual members often have distinctive personalities.

The Dalradian Supergroup is made up of the Grampian, Appin, Argyll and Southern Highland groups.

The Grampian is the solid foundation of the Dalradian, fairly calm and ordinary: the bass guitar player of the supergroup. It is a 7-8 kilometre thickness of sandstones and muddy sandstones*. In Ireland, Grampian Group sediments are found only in North Mayo.

The Appin is the lead singer: shallow, good looking and gets lots of attention. Its made up of sandstones, limestones and more muddy sediments all deposited on a marine shelf in shallow water. Now somewhat changed, it contains some gorgeous rocks.

Famous ‘Connemara marble’ which is from, er, Connemara in Ireland. Picture credit.

The Appin group is found in the heart of Connemara, also across Mayo and Donegal.

The Argyll is the lead guitar. It’s deeper than the Appin and has been through some pretty intense times – brushes with death in fact. It contains the familiar sandstones and muddier sediments, but also more exotic sediment types.

Twice in the Irish Dalradian there occurs an odd pattern of rock-types. First there is a layer of sediment filled with angular fragments with a wide range of sizes, called a diamictite. A number of subtle features show that it is sediment left behind by a glacier – it is a tillite. Immediately above is a layer of carbonate, a limestone or a dolomite. Such rocks usually form in nice warm parts of the earth so the association with glacial deposits is odd. The first of these tillilte-carbonate pairs can be traced across the Dalradian, indeed across the world. These are ‘snowball earth’ deposits. Some believe that at this time the entire earth was covered in ice, with glacial deposits forming near the equator. The overlying ‘cap carbonates’, contain unusual carbon isotope compositions suggesting to some that life on earth nearly died at this time. This happened not just once, but twice in the Argyll.**

Picture of Argyll group sediments making up the Twelve bens mountains of Connemara. Image from Guilhem Boyer on Flickr under Creative Commons.

The Argyll is rounded off with molten lava spilling into the sedimentary basin. Dangerous to be around for sure, but the Argyll makes the supergroup as a whole much more interesting and ‘edgy’.

The Southern Highland group is the drummer: completely crazy. The ground’s falling away under your feet, with sediments pouring into deep water and there’s another snowball earth episode***, there are big lumps of serpentinite, plus molten lava keeps coming out of the ground: madness. There’s a problem with ‘groupies’ as well. Lots of areas of sediment that say they’re ‘with the band’ but no-one is quite sure. Some of these, rocks along the Highland Boundary fault in Scotland or in Clew Bay in Ireland are worryingly young as well – Cambrian or even Ordovician. They’ve caused a lot of arguments, as you can imagine.

Song about a break-up

The Dalradian sing sad songs, about break-up: continents who once ‘were as one’ but who gradually drifted apart. It was a ménage à trois, so it was bound to end badly.

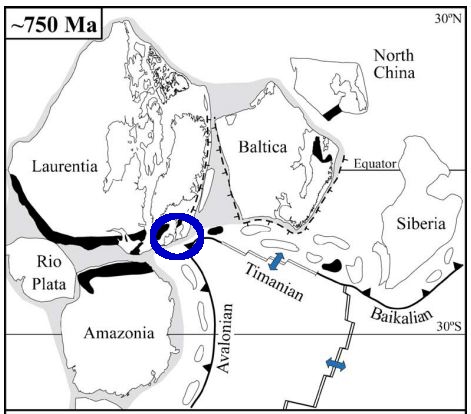

The song starts with the continent of Rodinia about 730 million years ago. This already had a rich and complex geological history which led to the creation of a large supercontinent consisting of pieces that now make up Scandinavia (Baltica), North American and NW Ireland and Scotland (Laurentia) plus Amazonia. Of course at the time these distinctions didn’t exist – it was simply a large single continent.

Cracks were starting to show, however. The Grampian Group formed in a rift basin, where Rodinia was starting to break-up. Early variations in the thickness of sedimentary layers suggest that faults were active during deposition. Times when the sedimentary basin became dramatically deeper also suggest tectonic involvement – active rifting was stretching the basin. There wasn’t a full break-up, however. Rifting ceased and a 30 to 40 million year period of calm saw the Appin group deposited in shallow waters under stable conditions.

The Argyll group saw rifting start-up again. By the end of the Argyll (600 million years ago) it became clear the split was going to be permanent. The stretching of the crust allowed the underlying mantle to melt, producing a ‘bimodal magmatic event’ with the intrusion of granites and the eruption of basaltic lavas. By Southern Highland group times, the sediments were forming in really deep water. Large bodies of serpentinite found in Ireland suggest the crust was stretched so much that material squeezed out from the underlying lithosphere.

This final extreme stretching marks the opening of a new ocean, called Iapetus. The opening of Iapetus created sedimentary basins all along the Laurentian margin. The Fleur de Lys Supergroup in Newfoundland and the Eleonore Bay Supergroup in Greenland were deposited in adjacent, equivalent basins. Further south in the US Appalachian belt, sedimentation associated with the opening of Iapetus starts only in Cambrian times.

Sing something simple?

I’ve told a nice simple tale, based on current scientific consensus, but it used to be much more complicated. The problem is that these are no longer sediments. Key concepts in both metamorphic and structural geology were developed on these contorted, baked and squashed rocks. Seemingly simple things like identifying the base of the Dalradian is extremely difficult as the rocks below are often also metamorphosed sediments, first transformed before the Dalradian and then deformed and heated again alongside it. Drawing a line between two types of schist requires extremely careful analysis.

The Dalradian is intruded by many granites. Most are older than the deformation, but some are younger, intruded into deep sediments in the Dalradian basin while sediment was still settling on the surface above. A date of 590Ma for one of these ‘Older Granites’ caused years of academic chaos in the 1990s as the granite was initially (incorrectly) thought to post-date the deformation, meaning that any younger sediments couldn’t belong to the Dalradian.

Geological histories hinge on tiny facts. The age of single zircon grain, a fabric wrapping an andalusite crystal: great geological narratives are built from or destroyed by such tiny pieces of evidence.

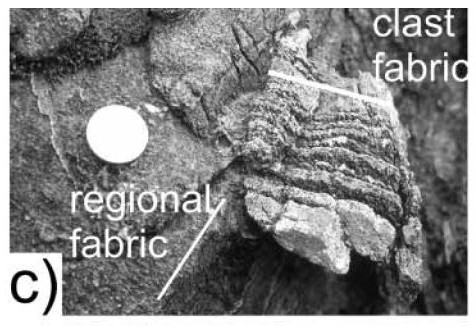

There is one inconvenient fact that might bring the whole of the simple story crashing to the ground. Respected researchers working in Donegal (Donny Hutton and Ian Alsop) have mapped an unconformity within the Argyll group. This could be consistent with our story – unconformities can form within sedimentary basins – but they interpret it as an orogenic unconformity. Based on various lines of evidence, including a tectonic fabric within sedimentary clasts above the unconformity, they infer a entire episode of mountain building took place during the gap in sedimentation shown by the unconformity.

So is the Dalradian a single package of sediments formed during the opening of an ocean, or two packages separated by a previously unrecognised period of mountain building? I’ve no idea, but hopefully time will tell.

Regardless, everyone agrees on what happened next. Iapetus no longer exists: it opened and then it closed, moving the Dalradian from a sedimentary basin into the core of a mountain belt. That’s where we’re going next.

——————————————————————————————————————-

*they’re not sandstones any more, but we’ll come to that

** the first, the “Port Askaig Tillite” is correlated with the Sturtian global event at c. 700Ma. The second ‘Stralinchy diamictite’ with the Marinoan at c. 635Ma

*** the Inishowen and Loch na Cille beds are correlated with the Gaskiers global event at c. 580Ma

References

L. Robin M. Cocks, & Trond H. Torsvik (2005). Baltica from the late Precambrian to mid-Palaeozoic times: The gain and loss of a terrane’s identity Earth-Science Reviews DOI: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.04.001

D.H.W. Hutton, & G.I. Alsop (2004). Dalradian Supergroup of NW Ireland

Evidence for a major Neoproterozoic orogenic unconformity within the Dalradian Supergroup of NW Ireland Journal of the Geological Society DOI: 10.1144/0016-764903-094

David Stephenson, John R. Mendum, Douglas J. Fettes, & A. Graham Leslie (2013). The Dalradian rocks of Scotland: an introduction Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association DOI: 10.1016/j.pgeola.2012.06.002

Pingback: Stuff we linked to on Twitter last week | Highly Allochthonous

very thanks for this brief but complete and exahustive description.

A big thank you, for your succinct, insightful and entertaining blog posts.

You’re welcome!

Pingback: The Grampian / Taconic orogeny in Ireland – when arcs attack | Metageologist

Pingback: Structural Geology by the Deformation numbers | Metageologist

This made revising the Dalradian much less dull. Thanks!

Pingback: Telling stories about Irish Geology | Metageologist

Beautiful specimens, I have always loved geology and rock hounding it is so interesting and enjoyable.

Pingback: New Scottish Oil field discovered (470 million years too late) | Metageologist

I love your blog! As a deep time paleoclimate person I have to point out though, there is no good evidence whatsoever that the Gaskiers glaciation was a “snowball Earth” event of the same sort as the Sturtian and Marinoan. That was a way-too-quick assumption made during the early phases of Snowball Earth geology — that all Precambrian glaciations would be snowballs. But IMHO the fact that there’s no evidence for near-equatorial ice during the Gaskiers is exactly why it’s exciting: it actually resembles Phanerozoic icehouse intervals, and in that sense might represent a more “modern” behavior of the climate system.

Pingback: A wee isle’s mighty geology – On the Rocks