Accretionary Wedge #37 called for examples of ‘Sexy Geology’. Here’s mine:

You always remember your first time.

I was a young man, freshly graduated and I’d somehow persuaded the government to give me (just) enough money to spend three years studying for a geology doctorate. Once spring arrived I eagerly set off for my field area. I’d been here before, but chaperoned on a undergraduate field trip. Now it was just me and the field-area, alone at last.

I spent most of my first field season with a small hill called Currywongaun. She’s a lovely thing: a glacially scoured lump of gabbro facing the Atlantic in Connemara, Western Ireland. The view is beautiful, the rocks are beautiful and sexy.

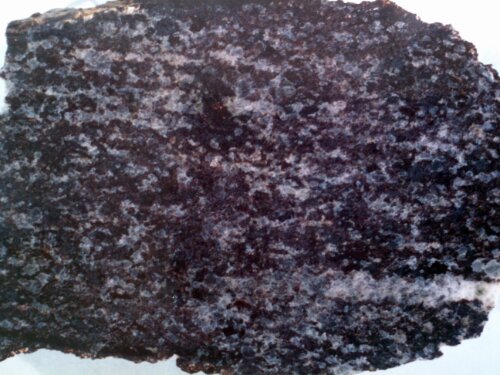

Gabbro is lovely stuff, with a touch of the exotic coming from its origin in the mantle. Most gabbro intrusions are petrologically interesting but structurally simple. Not my Currywongaun, it has modal layering, sure, but its orientation varies wildly and sometimes it’s folded. It is also has a fabric defined by the igneous minerals, showing that the magma itself was deformed while it was still partially molten. It is a syntectonic intrusion, emplaced not into the edge of an opening ocean basin, like the Cuillins or Skaergaard but into an actively deforming mountain belt.

Magmatic fabric in syntectonic gabbro

The base of the hill covers the edge of the intrusion and the rocks beneath. These are the sorts of rocks that get fans of structural geology all hot and bothered: mylonites, with lots of consistent shear sense indicators. Two sets of fabrics too, high temperature ones related to thrusting parallel to the intrusion edge and lower-grade cross-cutting extensional shear zones recording orogenic collapse.

Fancy a bit of metamorphism? Me too. Rocks close to gabbro get very hot indeed and metasedimentary xenoliths on Currywongaun have corderite-spinel-orthopyroxene assemblages; virtually all water (found in minerals such as muscovite) has been driven out of the rock due to extremely high temperatures. There’s a nice aureole around the intrusions as well which is large and high temperature (sillimanite isograd) since the rocks were already fairly hot (500 °C).

Cordierite-spinel-orthopyroxene granulite facies xenolith

A bit of mystery can be sexy too. There was an odd lens of an off-white rock, kind of a streak across the hillside, that I couldn’t quite identify in the field. Once back in the lab, armed with thin sections, I could piece together a story to explain the mystery.

Responding to powerful forces from deep within, the mafic magma forced its way deep into already hot metamorphic rocks. It crystallised into gabbro, became rigid and immediately the contrast in rheology with the softer reforming rocks around it created a zone of thrusting along its edge (I found sheath folds). The host rocks quickly responded, they were heated and metamorphosed with reactions that produced granitic melt and lots of hot fluids. These were forced back into the intrusion, altering it, transforming it. My mystery sample? Well, the gabbro is noritic, rich in orthopyroxene which when moistened is altered to everyone’s favourite amphibole, cummingtonite.

Sheared cummingtonite (with minor plagioclase and lichen)