Festering Questions from the West Virginia chemical spill

Cross-posted at Highly Allochthonous

![]()

The massive impact of last week’s chemical spill into the Elk River in West Virginia continues to cause hardship for the up to 300,000 people affected by the water ban and to pose tough questions for scientists and authorities involved with assessing and mitigating the spill’s effects on central West Virginia’s water supply.

Before Thursday morning, West Virginia’s Elk River was a well-known river for fishing and the sole water supply for the city of Charleston and populations in parts of nine counties. On Thursday morning, West Virginia Department of Environmental Quality Division of Air Quality was alerted to licorice or anise odor and traced the source to a leaking tank at a Freedom Industries facility located on the bank of the Elk River. The leaking tank contained 4-methylcyclohexane methanol, a chemical used in frothing during the coal washing process. The tank has been described as “antique” and was made of riveted stainless steel, which is an old construction technique. Unfortunately, the leaking tank was located near the river bank, and up to 7500 gallons of the chemical made it into the river. (Here’s what the site looks like from the river) Even more unfortunately, the water intake for West Virginia American Water was located only one mile downstream. West Virginia American Water is the major water supplier for 9 counties in central and southwestern Virginia, including the state’s capital, Charleston. Water treatment plants typically aren’t designed to remove industrial chemicals, and West Virginia America Water wouldn’t even have known to test for this one. At some point Thursday afternoon, the dots were connected and a water ban was put in place for anyone served by the water supply. Residents, businesses, and institutional facilities were told not to use the water for drinking, cooking, bathing, or washing clothes or dishes. The only allowed uses are toilet flushing and fire fighting. As of Sunday afternoon, three days after the spill occurred, the water use ban is still in place, state and federal emergencies have been declared, and FEMA and the National Guard are distributing bottled water and water from tanker trucks.

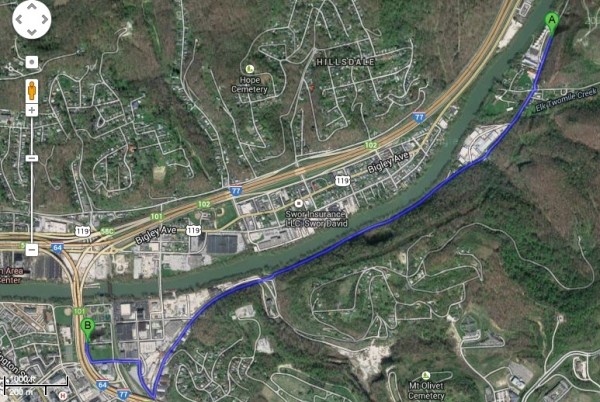

Freedom Industries site adjacent to the Elk River, upstream of Charleston, West Virginia. Image from Google Maps.

Point A indicates the Freedom Industries site and Point B indicates the water treatment plan. Image from Google Maps.

There aren’t a lot of data on the toxicology or safe levels of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol (MCMH) in water. We know that it is an organic solvent and a light non-aqueous phase liquid, which might be why there have been no reports of fish kills, since fish are hanging out in warmer, deeper pools at this time of year. Deborah Blum did some sleuthing and surmising from related chemicals, and so far the health effects appear to consist of a lot of people worried about symptoms but few people having problems clearly related to the spill. But the axiom of not ingesting industrial chemicals still stands. Officials are scrambling to find out what they can from the chemical’s manufacturer and to test samples to determine what level of contaminant is actually in the water supply. At some point, the state decided that a level of less than 1 part per million (1 ppm) of the contaminant was safe, and now the goal seems to be to have the water treatment plant consistently producing water at with contaminant levels lower than 1 ppm. There will also be some delay between samples being collected and the test results coming in, though it sounds like they may be making rapid on-the-ground strides in the rate at which they can test samples in four labs that have been set up for this task. Some reports say the state reported river water concentrations of MCMH had declined to 1.7 ppm on Friday, from 3 ppm. No numbers seem to have been released Saturday or Sunday, though NBC News is reporting on a news conference indicating 0 ppm going into and out the water treatment plant on Sunday morning. This article from the Bluefield Gazette gives some idea of the plan to flush parts of the massive water distribution system, which goes over mountains. All indications are that it will be days more before the water ban is lifted for everyone.

As an outside observer to this disaster, gleaning what I can from the media reports, here are my questions about the past, present, and future of the central West Virginia water supply.

- Why was a tank farm allowed to locate on the river bank only a mile upstream of a major municipal water supply intake? And if the tank farm was upriver before the water treatment plant was built, what safety concerns were raised in selecting that site?

- Were any special emergency procedures in place at either the industrial facility or the water treatment plant given this proximity? (I can find a risk management plan for the water treatment plant to deal with its risk of spilling chloride, but I can’t find anything similar for Freedom Industries or how the water treatment plant planned for risks of spills upstream from its facility. These plans may exist off-line.)

- How was an acceptable maximum contaminant level of 1 part per million decided upon?

- When the water treatment plant is producing less than 1 part per million of MCMH in the water supply, how will they test and ensure that all parts of the water distribution network are at that level?

- What will the flushing recommendations be for water users? How will the recommended flushing times be determined?

- Will there be longer term monitoring of MCMH levels at various points in the distribution network to ensure that levels remain below the acceptable maximum contaminant level?

- Will there be long term studies of the environmental and human health effects of the exposure, particularly on vulnerable populations like children?

- Most importantly, how will this incident change policy and procedures in this region, in West Virginia, in the coal processing industry, and in the nation?

Based on what I’ve learned, the risks of this human-caused disaster could potentially have been substantially mitigated by more stringent watershed planning that prevented the tank farm from operating so close to the river bank so close upstream of the water treatment plant and tighter regulation and routine inspection of the tank farm and its safety procedures. If the spill had still occurred even with those risk reductions, it would have been useful to have more information on the toxicology of the chemical that spilled (and all industrial chemicals) to provide better guidance on what maximum contaminant level is acceptable. As Deborah Blum points out, “Our Toxic Substances Control Act is more than 35 years old and we (by which I mean Congress) haven’t conjured up the backbone to update and strengthen it as of this date.”

This spill and its disruption of West Virginians lives shows what can happen when environmental regulations are not stringent, rigorous, and routinely enforced. The spectre of 300,000 US residents unable to drink or bathe in their tap water for days on end should stick in our collective consciousness for a long time. We don’t need to invoke the threat of terrorists or climate extremes to disrupt our water lifelines; West Virginia reminds us that business as usual can do that too.