Chris: Any PhD student who stays in research tends to find that they never truly escape their thesis. It may be submitted, defended, and even published, but the thing that took a good chunk of your time, sweat and sanity during your early-to-mid-twenties can still find ways to nag at you. Things you didn’t quite solve, new questions replacing the ones you did solve, other peoples’ research in the same area which inspires and frustrates you in equal measure: all these things nag at you every so often, and perhaps call you to reapply your scientific powers.

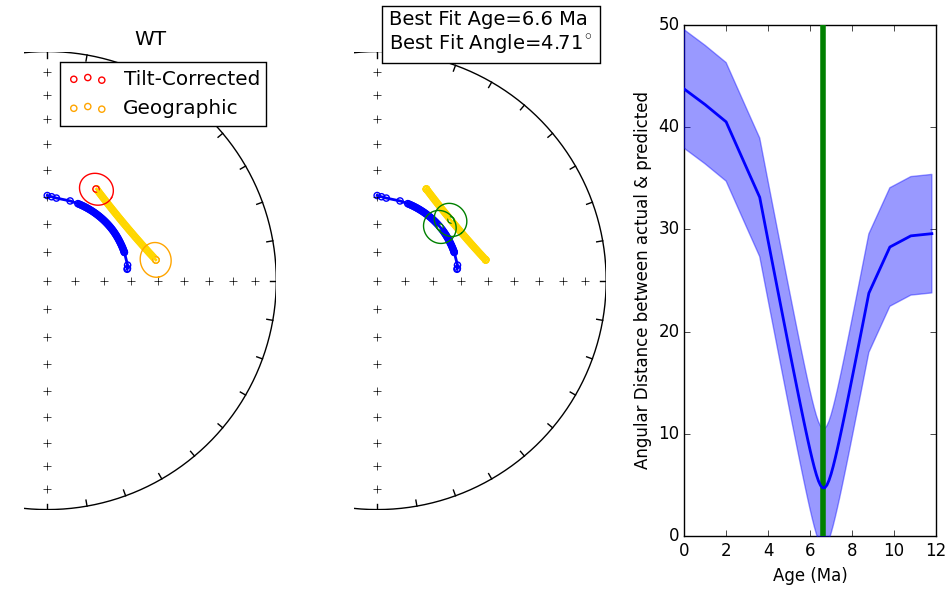

Which is why, fully ten years after he submitted his PhD thesis on New Zealand tectonics, Chris found himself presenting some new research on New Zealand tectonics at the GSA Annual Meeting in Baltimore. New Zealand is an actively deforming region on a plate boundary. Part of that deformation involves blocks of crust being rapidly rotated about a vertical axis, which is something that can be detected by paleomagnetic measurements. However, the magnetic mineral most common in the rocks in the area of interest is also a bit sensitive and prone to being reset, which is quite hard to detect and gives quite misleading results if it is not. Chris is developing a new method that uses a specified model of deformation and rotation to predict what magnetic field direction the actual sampling localities should ‘see’ at all points in its history (blue), and seeing if the real data (yellow) can be consistently fit to a particular model or not. For the locality presented in this figure, we get the best fit to the current rotation model if there was a remagnetisation event about half way between when this rock formed 12 million years ago and the present.