The word terrane has a very specific geological meaning. Usually short for tectonostratigraphic terrane, they’ve been defined as “fault-bounded crustal blocks that preserved a geological record distinct from that of adjacent terranes” (Jones

et al., 1983).

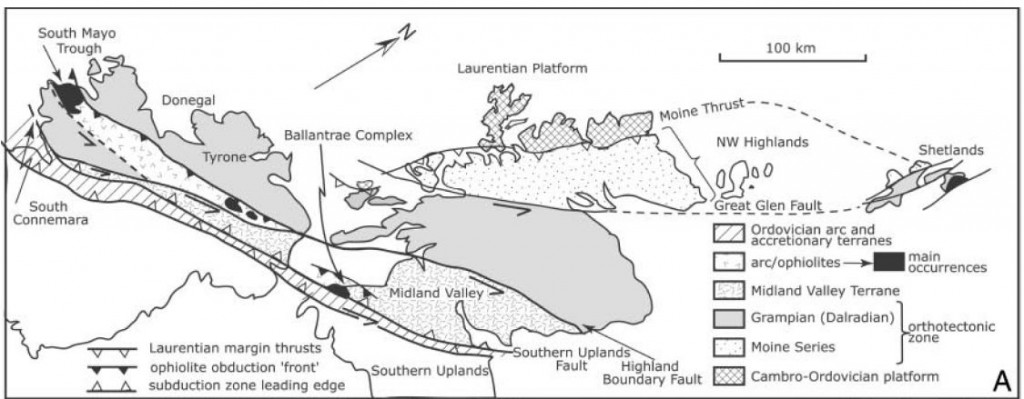

The concept was first coined as a way of understanding the rocks of the North America Cordillera. We know now this area is a collage of different terranes that were added (“accreted”) to the proto-North American plate (Laurentia). Some formed part of the core continental plate. Others formed within the vanished ocean, as pieces of volcanic arc, accretionary wedge or oceanic crust. Others are pieces of continental crust that came from further afield, such as Arctic Norway.

Getting around British Columbia or Alaska is hard and dangerous (think helicopters and grizzly bears). Doing geology in the West of Ireland is much easier (think mini-buses and pubs). This explains its popularity for university field trips. During the Ordovician, various pieces of oceanic and arc crust were scraped onto the Laurentian continent in what is now Ireland. This makes it good terrain for terrane training1.

Getting a handle on a complex jumble of terranes requires geologists to draw on a whole range of geological data. There are some specific concepts that relate to terrane analysis, all nicely illustrated in the west of Ireland.

Fossil evidence

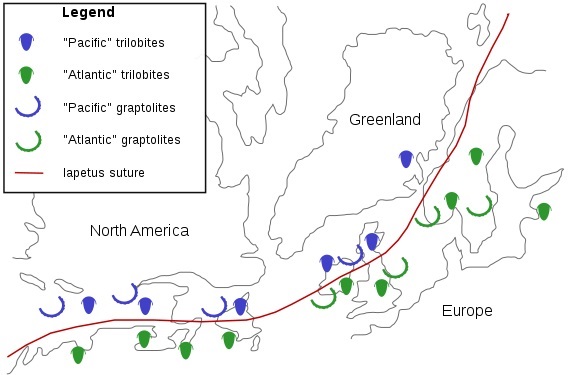

Fossils can be used to get a handle on whether particular terranes were near each other or not. A classic example of this comes from the British Isles. In the 1940s, Stuart McKerrow was a young man on the Atlantic convoys, constantly menaced by Nazi submarines while ferrying American materiel to a hungry Britain . While not winning medals for bravery2, he found time to ponder a mystery. Cambrian rocks in Newfoundland, one end of his dangerous journey, contained trilobites that closely matched fossils from his native Scotland. Oddly trilobites of the same age from England and Wales were very different. Surely it would have made more sense if the fossils from opposite sides of the Atlantic were different, in the same way modern animals are different across oceans.

Of course now we understand that the Atlantic did not exist in the Cambrian. During his later career as a geologist at Oxford University, Stuart McKerrow joined others in showing that the line of a vanished ocean, Iapetus, can be traced across the British Isles. Wales and Scotland started off on opposite sides of this ocean. At certain times, species that live in the deep sea were the same, but shallow water (benthic) animals were different – something that requires an intervening body of deep water. His work involved detailed studies of fossils on both sides of the Atlantic, picking out the pattern of plates and terranes, showing how they moved during the closure of the Iapetus ocean.

Stitching pluton

A stitching pluton is an igneous intrusion that joins two or more terranes together. Simple field relationships will show that the intrusion cuts into the rocks of the terranes. The intrusion is therefore younger than them, plus the terranes were adjacent when the magma was intruded. Dating the age of intrusions is relatively simple which means stitching plutons are a simple way to constrain when two terranes were joined.

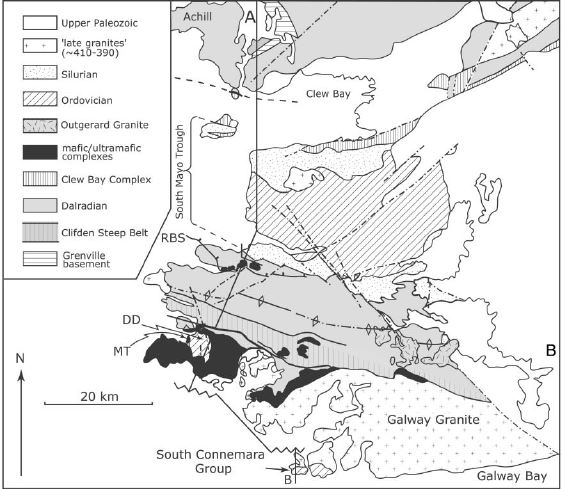

The Galway Granite is a large batholith found on Connemara’s south coast. To its north are the metamorphic rocks of the Dalradian Supergroup. Formed on the Laurentia continent, these rocks were deformed by the Caledonian/Taconic orogeny around 475-460Ma. To the South of the Galway Granite, the South Connemara group is a tectonic melange including abyssal cherts and mafic volcanics with chemistry suggesting they formed at a mid-ocean ridge. These rocks formed at a Ordovician subduction trench.

These two terranes formed in very different tectonic environments, but by 420 million years ago they were next to each other, ready to be permanently stitched together by the Galway granite.

Sedimentary linkages and overlap assemblages

Another way of showing two terranes have become close to each other is to show that pieces of one were eroded into a sedimentary basin on the other. For example conglomerates in the trench rocks of the South Connemara group contain distinctive rock-types common in the Connemara Dalradian terrane to the north. This would suggest the two terranes were nearby while the South Connemara group was forming – that the subduction trench lay along a line now obscured by the Galway Granite.

In a similar way, detailed studies of heavy minerals in the South Mayo Trough and samples of distinctive igneous rock types can be used to date when the Connemara terrane moved close by. Connemara is the only piece of Dalradian found to the south of the Iapetan arc terranes. For this reason it is thought to have been shifted into its current position by strike slip faulting during the Ordovician.

There is a sedimentary linkage between Connemara and the South Mayo rocks – a set of Silurian rocks that lie unconformably on both terranes. This puts a upper limit on the timing of relative movement. Unfortunately it also obscures the actual contact. The details of how Connemara arrived in its current location remain a mystery.

The concept of terranes is extremely important. Terranes form a vital bridge between the bewildering detail that a field geologist has to deal with and the simple concepts of plate tectonics.

References

Jones, D.L., Howell, D.G., Coney, P.J., and Monger, J.W.H., 1983, Recognition, character and analysis of tectono-stratigraphic terranes in western North America, in Hashimoto, M., and Uyeda, S., eds., Accretion Tectonics in the Circum-Pacific

Region: Terra, Tokyo, p. 21–35.

Dewey J.F. (2005). Inaugural Article: Orogeny can be very short, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102 (43) 15286-15293. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0505516102

Brown D., Ryan P.D., Ryan P.D. & Dewey J.F. (2011). Arc-continent collision in the Ordovician of western Ireland: stratigraphic, structural, and metamorphic evolution, Arc-Continent Collision, 373-401. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-88558-0_13

Great post! An excellent explanation of a complex topic. I feel a holiday in Ireland coming on.