Geology and history have much in common. Both seek to understand the past by objective analysis of the traces it has left in the present. Both arose from the application of hand and mind to the study of particular things (outcrops of rock, historical documents). Both now benefit from more technological forms of analysis, as illustrated by a paper in this month’s Geology. In it, Anne-Marie Desaulty (Lyon) and Francis Albarede (Houston) apply techniques usually used in the geosciences to historic silver coins.

They dug up the English king Richard III from a car park recently. They linked the skeleton to the historical person using DNA analysis. Isotopes can be used like DNA but for ‘stuff’ instead of people. Most chemical elements have different isotopes and usually chemical or physical processing doesn’t change the isotopic composition. In some cases the processes that formed the stuff in the first place produced distinctive isotopic signatures. This means isotopic analysis can tell you where the stuff came from, even if there is no other way of knowing. In the geosciences isotopic analysis is used a lot – it tells us the ‘Martian meteorites’ really are from Mars – but its use in history is much rarer.

Silver groat from reign of Mary I of England.

We take it for granted that our currency is made from cheap materials – cotton paper or base metals – but this is a relatively modern innovation. In Europe coins were long made of gold and silver – materials that were laboriously mined and carefully transported across the world. Our authors use isotopic techniques to look at the silver (and trace lead and copper) within silver coins from England and trace where the silver came from. They studied coins from Mediaeval to Early Modern times: a fascinating stretch in world history.

Europe in the 16th century is arguably the first place to experience ‘globalisation’. Technological innovations from China such as printing and gunpowder were catalysing dramatic change across the continent. Spain and Portugal were building empires in South America and bringing back such transformative substances as tobacco, potatoes, beans, corn and chili peppers. Spain was also digging up vast quantities of silver from mines in Mexico and in Peru Bolivia at the ‘rich mountain’ of Potosí.

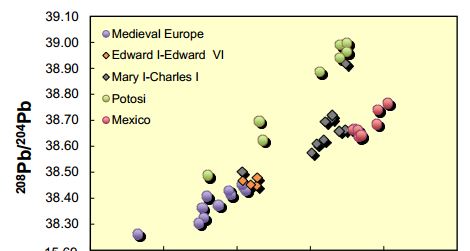

A portion of figure DR1 from additional material.

Looking at coins from the 13th to the 17th centuries, our authors are able to trace where the silver in them came from. The early Medieval coins are linked to European sources, mines in central Europe. At around 1553 they can see South American silver arriving and that source dominates nearly all later coins. The dilution of European sources is to be expected: we know that vast volumes of silver were mined. What is surprising is that nearly all of the silver comes from Mexican sources and not Peru Bolivia, despite Potosí having the larger output.

To explain this, our authors think globally. It’s known that much of the Spanish silver ended up in China, who adopted silver money in the 16th century. Being the most advanced nation at the time, China wanted little from the outside world other than precious metals. If European barbarians wanted their silks (or later their tasty tasty tea) they had to pay in gold or silver. This silver was thought to have flowed from Spain via Europe, but the isotopic evidence suggests that for Potosí silver this didn’t happen. For Mexican mines, the obvious outlet was by land into the Gulf of Mexico and west via ship to Europe. For Potosí the Pacific was nearer and our authors conclude that most of it ended up in China having travelled east via the Spanish empire in the Philippines.

So, silver was flowing around the world 500 years ago and isotopes allow us to track it. The potential of this technique to track such global flows is very exciting. I’ll end on a local note, however. The paper talks of an ‘apparently abrupt surge of Mexico silver in English silver coinage during the reign of Mary I’ ending the dominance of European silver. Their focus is predominantly on economic history, but surely it is relevant that the year after becoming Queen, Mary I married Philip III of Spain. Their marriage in Winchester Cathedral was a glorious occasion and descriptions emphasise the quantities of gold decoration. I’ll wager there was a fair bit of silver from Mexico around too.

Desaulty, A., & Albarede, F. (2012). Copper, lead, and silver isotopes solve a major economic conundrum of Tudor and early Stuart Europe Geology, 41 (2), 135-138 DOI: 10.1130/G33555.1

Another very interesting post! I have just a minor quibble … Potosí is in Bolivia not Peru. For example, see http://plantsandrocks.blogspot.com/search/label/Diablada

It’s just completely wrong that Potosi silver was more likely to end up in China via Pacific. It was exactly the Manila trade route from Acapulco which was monopolized by Mexican merchants while all Potosi silver (in theory) had to go via Panama to Europe. And by Mary’s reign (who btw. married Philipp II., not I.), the direct route via the Pacific was not used at all.

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude!

Thanks, However I am going through issues with your RSS.

I don’t know the reason why I am unable to join it.

Is there anyone else having similar RSS issues? Anybody who

knows the answer can you kindly respond? Thanx!!

Pingback: Cornwall: tin, pasties and the world | Metageologist