The Black Sea has only a tenuous connection to the rest of the world’s seawater. The Bosporus are not only very narrow, but very shallow: at one point in the channel, the water is only 30m deep. At the height of the last ice age 18-20,000 years ago, more water was stored in much larger polar ice caps and global sea-level was about 130 metres lower than at present; this is more than enough to have left the Bosporus high and dry, and the Black Sea completely cut off from the Mediterranean. Past studies of sediments dating from this time confirm that the Black Sea basin was indeed a freshwater lake, filled to about 150 metres below present day sea-level; they also indicate that there was an abrupt switch to marine conditions between 6000 and 7500 BC, when sealevel rose enough to send a torrent of marine water rushing into the Black Sea, flooding tens of thousands of square kilometres of what was, up to that point, dry land.

A catastrophic flood in Asia Minor, back in the mists of human prehistory? Cue endless twittering about certain myths in certain holy books whenever this story comes up in the media. An interesting new paper in Quarternary Science Reviews by Chris Turney and Heidi Brown is no exception. However, although their work suggests that there may be a link between this event and an important transition in European culture, it makes the (in my opinion) already tenuous alleged connection to ‘Noah’s Flood’ (there was no 40 days and 40 nights of rain. There was no rain – just 40 years of inexorably rising water as the Black Sea Basin filled up to sea-level. Even accounting for a few thousand years of distortion and exaggeration, that seems a bit of a stretch) even more difficult to support.

At the heart of this study is the detailed analysis of many, many radiocarbon dates, in the quest for an accurate chronology. If you want to examine the possible effects of a geological event on prehistoric cultural evolution, you need to have accurate dates for both the event – in this case, the Black Sea flood – and the relevant cultural changes – in this case, the spread of Neolithic culture, which represents the transition from a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more sedentary one based on agriculture and pot-making. Without a robust chronology, you can end up with actual causes appearing to happen after their effects, or occurring hundreds or thousands of years too early, both of which make it very difficult to unravel the true story.

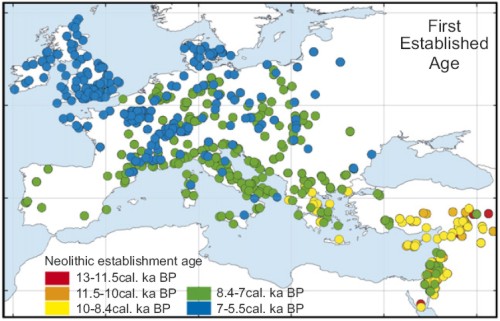

The change to marine conditions in the Black Sea is clearly marked in the sedimentary record: out go the shells of freshwater molluscs, in come the shells of salt-tolerant species. In between is a reworked debris, or ‘hash’, layer, which probably records the Bosporus breakthrough itself. Radiocarbon ages of the youngest freshwater mollusc provide a maximum age for this debris layer; the oldest marine molluscs provide a minimum age. A best fit model for all the available age data suggests that the sea first forced its way into the Black Sea between 8350 and 8230 years BP (BP= before present, with ‘present’ defined as 1950), or around 6400 BC. This more precise date suggests an association with a specific geological event: the final collapse of the Laurentide ice sheet which covered North America during the last glacial period (Ole has more on this aspect of the study). More interesting, though, is how this date correlates precisely with a sharp acceleration in the spread of agricultural societies across Western Europe. The figure below, taken from the paper, summarises the Neolithic archaeological record:

After the first Neolithic sites (red dots) sprung up in the Near East between 13 and 11.5 thousand years BP (9-11,500 BC), the initial spread of agricultural practices was apparently pretty slow – almost 5,000 years later, in 8,500 BP (6,500 BC), Neolithic settlements had appeared in Turkey and Greece (yellow dots), but most of Europe was still happily hunting and gathering. In the 1500 years following the breach of the Bosporus, however, the pace of change really picked up, and by 7,000 BP (5,000 BC) Neolithic sites could be found across most of continental Europe. The neat explanation, therefore, is that prior to 8,500 BP there were Neolithic settlements on the ancient shores of the Black Sea; as the basin filled up with increasingly saline water, the original inhabitants of these settlements were forced westward into new pastures, where they set about establishing new agricultural settlements at the expense of the native hunter-gatherers.

It may be a neat picture, but there are still some missing pieces. It is still not proven, despite some suggestive evidence from under the waves, that Neolithic cultures had reached the Black Sea region prior to 8,500 BP. And, as the figure above illustrates, no Neolithic settlements sprung up immediately to the west of the Black Sea at the beginning of the great European expansion, as you might expect if agriculturally-inclined people were moving away from the rising waters.

One thing does seem pretty clear to me, however: even if the inundation of the Black Sea did displace large numbers of people, it seems exceedingly unlikely that the story of this exodus is (rather imperfectly) preserved in the Biblical Flood account. They all moved west, whereas Babylon, from whose mythology the Biblical flood story was borrowed wholesale, is in completely the opposite direction. The story is wrong, and the source culture is wrong, although I somehow doubt that will stop the headline writers.

Comments (8)