I’m a long way from the current flooding chaos back in the UK which, along with the episode earlier this summer, has forced millions of people to face the shocking revelation that flood plains occasionally, erm, get flooded. Fortunately, my family live in a different part of the country, and friends who do live in the affected areas fortuitously live on hills (in fact, one rather sensibly checked the Environment Agency’s flood maps before she bought her house). I, of course, am currently living at an altitude of 1800m in one of the few major cities in the world not built on a major river; most residents here need to worry far more about acts of their fellow men than Acts of God.

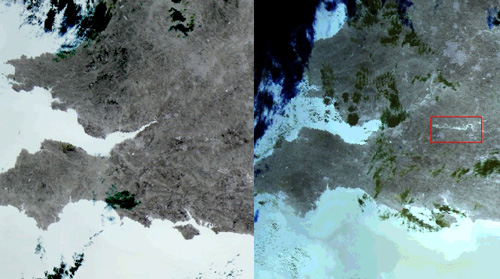

The European Space Agency has released some satellite imagery of the flooding, including this image of the overflowing River Thames (on the right), compared to a normal view.

The ESA release also has a nice ‘before and during’ animation of radar images of south-west England, with dark splotches marking the course of the Severn and Thames much further upstream than normal, as they burst their banks and spread non-backscattering water over the landscape.

Of course, all this has engendered the usual confusion and propaganda (from both sides) over whether you can lay the blame on our warming of the planet or not. For this particular event, you can’t: there are always going to be times when rivers burst their banks (resulting in the aforementioned flood plains that we are so keen to build on), and you can’t with any justification say ‘if the atmospheric CO2 concentration was at pre-industrial levels, then the intense rainfall which caused this flooding would not have happened’. The key question is how often you get a serious flood, and this is where anthropogenic climate change comes in: it can alter long-term weather patterns and change the underlying probabilities of an extreme event. What was a ‘100 year flood’ (of a magnitude that happens every century on average) could become a 25 year flood. What was a 25 year flood could become a 5 year flood. And, conversely, a 5 year flood could become a 25 year flood. The fingerprints of climate change can only be detected through trends, measured over a number of years – not a single headline-grabbing calamity. Such a trend is exactly what a paper published in Nature last week (with almost supernaturally good timing) claims to be seeing. From the abstract (see also the news article):

Here we compare observed changes in land precipitation during the twentieth century averaged over latitudinal bands with changes simulated by fourteen climate models. We show that anthropogenic forcing has had a detectable influence on observed changes in average precipitation within latitudinal bands, and that these changes cannot be explained by internal climate variability or natural forcing. We estimate that anthropogenic forcing contributed significantly to observed increases in precipitation in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes, drying in the Northern Hemisphere subtropics and tropics, and moistening in the Southern Hemisphere subtropics and deep tropics.

So it may well be that the next time flooding of this magnitude hits the UK, I’m not going to have amassed too much more grey hair. And this is clearly an issue for house-building policies: if building on flood plains is short-sighted, building on flood plains that we think are going to flood much more often – even with some efforts at mitigation – is reality-denial of epic proportions. At least we Brits are not alone…

Comments (3)